A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (52 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Lord Edward’s arrival had coincided with the beginning of General Lee’s counteroffensive against McClellan. Bored with his leaky tugboat, Francis Dawson resigned from the Confederate navy to join an artillery battery commanded by Willie Pegram, a nephew of Captain Pegram’s. On June 26, Pegram’s battery was ordered to cross the Chickahominy River, northeast of Richmond. According to Lee’s plan, the troops under General A. P. Hill (to which the battery belonged) were to form one element of a four-part attack against McClellan’s somewhat incoherently placed divisions. If all went well for Lee, the Federal invaders would be attacked on every side and could disintegrate.

But one vital piece was missing: Stonewall Jackson and his men had not yet arrived from the Shenandoah Valley. After anxiously waiting until three in the afternoon, General Hill ordered his men to begin their assault without him. “The guns were instantly loaded, and the firing began,” Dawson recalled. “A solid shot bowled past me, killed one of our men, tore a leg and arm from another, and threw three horses into a bloody, struggling heap. This was my chance, and I stepped to the gun and worked away as though existence depended on my labours.”

67

He worked feverishly until a blow knocked him off his feet. “That Britisher has gone up at last,” he heard. Dawson examined his leg and saw that a shell fragment had ripped away six inches of flesh. But strangely, he felt nothing. “I went back to my post, and there remained until the battery was withdrawn after sunset.” Of the seventy-five men in Pegram’s battery, only twenty-eight were still standing.

Dawson managed to hobble for several miles to a field hospital. While trying to obtain some morphine for a friend, he saw surgeons, their bare arms smeared with blood, cutting and sawing into rows of limbs. Below one table lay “arms, feet, and legs, thrown promiscuously in a heap, like the refuse of a slaughter house.” Dawson decided not to stay and obtained a ride on an ambulance going to Richmond. His adventures with Willie Pegram had been brief, but he was gratified to read about himself in the Richmond

Dispatch

a few days later as the “young Englishman” who had “received a wound while acting most gallantly.”

68

He was a hero, as tens of pretty young lady nurses told him every day.

Dawson soon began to regret his fame. When one of his friends in the Confederate navy, James Morgan, came to visit him, Dawson begged for his help. “The day was hot,” Morgan recalled,

and I found my friend lying on a cot near the open front door, so weak that he could not speak above a whisper, and after greeting him and speaking some words of cheer I saw that he was anxious to tell me something. I leaned over him to hear what he had to say, and the poor fellow whispered in my ear “Jimmie, for God’s sake, make them move my cot to the back of the building.” I assured him that he had been placed in the choicest spot in the hospital, where he could get any little air that might be stirring; but he still insisted that he wanted to be moved, giving as a reason that every lady who entered the place washed his face and fed him with jelly. The result was that his face felt sore and he was stuffed so full of jelly that he was most uncomfortable.… Shaking with laughter, I delivered his request to the head surgeon, who pinned a notice on Dawson’s sheet to the effect that “This man must only be washed and fed by the regular nurses.”

69

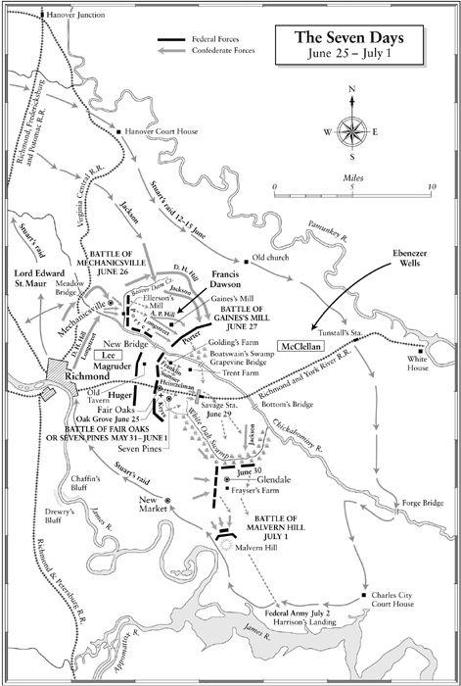

Map.9

The Seven Days, June 25–July 1, 1862

Click

here

to view a larger image.

The Battle of Mechanicsville, as Dawson’s engagement was called, was a costly disappointment for Lee. Jackson’s failure to arrive on time resulted in Confederate troops having to attack without adequate support. Lee was still feeling his way into his new command, but the one quality he did not lack was determination. The following day, General Hill’s troops once again led the assault. But by now Jackson and his men, including the Louisiana Brigade, had arrived and they too rushed into battle. Seeing his men stagger beneath a barrage of fire, Major Wheat galloped in front of the Louisiana Tigers, urging them to follow. Both he and his horse were immediately riddled with bullets. The fighting continued so hotly that Wheat’s body lay where it fell for twenty-four hours.

For the next seven days, beginning on June 25, Lee and McClellan clashed along the Chickahominy River, around the perimeter of Richmond, in one bloody encounter after another. Although McClellan lost none of these battles, he was unnerved by Lee’s attacks and began retreating southward, away from Richmond. Lee wanted to demolish “those people,” as he referred to the Federals, with another all-out attack on July 1. By now, the Union army was entrenched around Malvern Hill, fifteen miles southeast of Richmond. The terrain favored the Federal soldiers sitting atop the 150-foot-high plateau. McClellan still had 115,000 men with 100 pieces of artillery and, unlike their general, their nerves were holding steady.

The Confederate attack was so disjointed that isolated brigades ran forward only to be chewed up by artillery fire. This “was not war—it was murder,” a Confederate general later said of Lee’s failed assault. The Louisianans (minus Sam Hill, who was happily drawing up maps, thanks to some clever wrangling by his sister) were mauled by Irishmen in blue, including the 69th New York. The total Confederate loss on this terrible day was five and a half thousand, nearly twice the number of casualties sustained by the Federals.

11.4

About a quarter of Lee’s eighty-thousand-strong army was either dead or wounded. McClellan could have ordered a counterattack, and many of his generals urged him to do so, but he had lost the will to fight. The next morning, July 2, the mist lifted from the battlefield to reveal so many bodies that the terrain appeared to be masked by a bloody quilt. Some were dead, but many still crawled feebly like stricken insects. Despite having inflicted a stunning blow against Lee’s army, McClellan continued his retreat, and the Seven Days’ Battles were a strategic victory for Lee, despite his heavy losses. On June 3, McClellan had been five miles from Richmond; on July 3, he was thirty. The casualties for the two sides amounted to more than 35,000 men.

McClellan left behind a treasure trove for the undersupplied Confederates. “All along the road,” wrote an English observer, “cartridge boxes, knapsacks, blankets and coats may be picked up. The rebels, as they pass, generally cast away their own worse equipments and refit.… Here were cartridge boxes, unopened and perfectly new.”

70

Five days later, on the eighth, Lincoln sailed down to Harrison’s Landing on the James River in order to see the situation for himself. His impatience with McClellan was echoed all over the North. Only the general seemed to think that his withdrawal was nothing other than a “change of base.” The rest of the country called it a reckless squandering of a brilliant opportunity to capture Richmond and win the war.

Lord Edward St. Maur set off for Washington after the Seven Days’ Battles and arrived under a flag of truce at McClellan’s camp on July 15. He had planned to stay for some time, but his admission to having observed the campaign from the “other side” provoked a reaction from the Union officers “which was really childish,” he protested to his father. Unwisely, he fell into arguments with them about the reasons for the war and other sensitive subjects. Lord Edward’s opinions had undergone a complete transformation, just as the Southern propagandist W. W. Glenn had hoped. “I did not start with any feeling one way or the other,” he insisted, “but I defy any candid man to go south, without being convinced that this war must end in separation.” If the split did not happen soon, he expected it to become a long and “very cruel war.” He had heard from Southern officers that there had been instances of Louisiania regiments killing their Northern prisoners. “This,” decided Lord Edward, “is Butler’s doing.”

11.1

Northerners had pointed out to Vizetelly the staggering disparities between the two sides. The last economic figures before the war showed that the Southern states had 18,026 “industrial establishments,” the North, 110,274.

31

11.2

The Prince de Joinville excused McClellan’s performance, claiming that the general had been constantly hamstrung and interfered with by Washington.

11.3

France’s invasion of Mexico made the presence of Joinville and the Orleans exiles politically embarrassing, and they departed from America at the end of June. But Joinville continued to defend McClellan from abroad, publishing a long pamphlet, entitled “The Army of the Potomac,” which appeared the following October.

11.4

Among the Union wounded was a cousin of William Gladstone’s, twenty-one-year-old Herbert Gladstone, who had joined the 36th New York British Volunteers the previous year. He survived an agonizing journey back to the capital with a bullet lodged in his left leg, after which his family in England lost track of him.

TWELVE

The South Is Rising

Beast Butler—Palmerston is offended—Hotze and Spence join forces—Lindsay goes too far—The

Alabama

escapes—Déjà vu at Bull Run

“B

east Butler,” as the South dubbed General Ben Butler, was enjoying what the Scotsman William Watson called a “perfect reign of terror” over New Orleans. Watson received his discharge at Camp Tupelo and set off by train and steamboat to New Orleans. During his journey south, he witnessed unsettling scenes: Federal soldiers marching onto a plantation and putting down a slave revolt at gunpoint; Confederate “guerrillas” using women and children as human shields. When he reached New Orleans, Watson went straight to the consul, George Coppell, to ask for a certificate of British nationality. “He informed me that the certificate would be of no use or protection, if I violated neutrality. I then looked about for a day or two to see the state of things under Butler’s rule.”

1

Watson found a city ruled by whim—the whim of a Union soldier, a Butler-appointed bureaucrat or judge, or an anonymous informer. “Butler continued to hunt for treason, and all material that could contribute to it he confiscated. He found it existed extensively in the vaults of banks,” wrote Watson, “in merchants’ safes, in rich men’s houses, among their stores of plate and other valuables.”

2

A judicial ransom system was in effect. Men of means would be arrested on some unknown charge and their wives prevailed upon to secure their release by handing over thousands of dollars to a “fixer” who happened to know the right judge.

Watson had been in the city for only a few days when he experienced Butler’s justice for himself. It began with a thoughtless comment he made in a café. A short while later, Watson was accosted on the street by three men and forcibly marched to the customs house. He was questioned by detectives who “seized my pocket-book, as they had seen in it treasonable documents in the shape of bank-notes.” He asked to see a lawyer and to have his arrest made known to the British consul, which made his interrogators laugh. After a night behind bars, Watson was taken to see General Butler on the charge of having used “treasonable language.” Years later, the memory of his interview still made Watson bitter. Butler’s head “was large and flabby,” he wrote, “and nearly destitute of hair—except a little at the sides, which was just the color of his epaulets.” The general jeered at him and asked if he knew why he was there. “I said I was a British subject, and would have counsel to attend to my case. ‘Oh, a British subject of course,’ roared he. ‘I know that they are all British subjects now in New Orleans.’ ”

Butler’s manner throughout the interview led Watson to expect a lengthy prison term. Instead, he was sent before a judge, who examined his certificate of nationality and then offered him some words of advice about incautious jokes in a city under martial law. “I was quite astonished at having got off so easily.” His pocketbook was also returned, with some of the money still there, “which was considered a most extraordinary and unaccountable circumstance.”

3

Watson wondered if the presence of HMS

Rinaldo,

lately arrived on Lyons’s orders, had anything to do with his swift release. Butler, he thought, made a great deal of noise about foreigners and the interference of foreign powers, particularly “John Bull.” But it was all calculated to frighten, rather than eradicate, the foreign population. Nevertheless, Watson was determined to leave New Orleans. All he had to do was find a weakness at one of the checkpoints and sneak past the guards. One sultry summer’s day, Watson and two friends set off for a picnic and simply carried on walking.