A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (50 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

On May 14, Vizetelly informed readers of the

Illustrated London News

that he had transferred from the U.S. Army to the U.S. Navy. “The last you heard of me, [I] was waiting in St. Louis for a reply from General Halleck,” he wrote. The response to his request had been disappointing; Halleck had not officially barred him from the Army of the West, but he had forbidden him to use government transport. It amounted to the same thing, Vizetelly pointed out, since he could not paddle a canoe, “charter a steamer specially to carry me, or swim up the Ohio and Tennessee Rivers,” just to follow the army. Happily, he discovered that the naval authorities were indifferent to his presence. Vizetelly was granted permission to observe the river operations on the Mississippi.

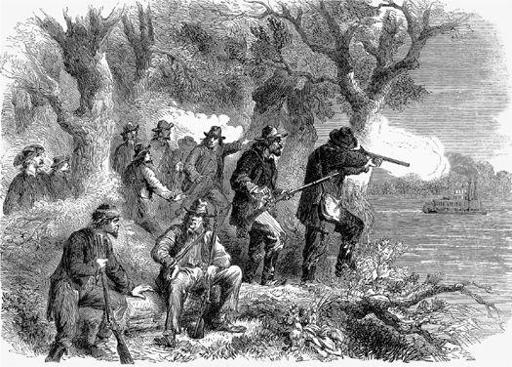

“Leaving St. Louis late in the afternoon,” wrote Vizetelly, “I found myself steaming down its rapid current in one of those floating palaces.” There seemed to be no shore along the river; “nothing but submerged forests for miles and miles back, with here and there a clearing showing the locality of a plantation.” His destination was Fort Pillow, the last Confederate obstacle before Memphis. Vizetelly remained on board for six weeks as the Union fleet wound its way down the Mississippi River. Despite the growing heat, he was often confined to his tiny cabin, as sharpshooters hidden in the tangled thickets along the river proved to be far too accurate for safety. Vizetelly was convinced that the South was wasting her men on a losing cause. “We find that each day the North is developing her gigantic resources,” he wrote. The South had no shortage of brave men, “but her army is growing weary.” “I have spoken with numerous deserters, prisoners, and others, and they have, with few exception, expressed themselves heartily sick of the war.”

30

11.1

Ill.20

Confederate sharpshooters firing from the banks of the Mississippi at the Federal fleet, by Frank Vizetelly.

At daybreak on June 6, the Union and Confederate flotillas steamed toward each other in their final confrontation. As the city of Memphis came into view, Vizetelly saw that a line of eight Confederate vessels waited to block them. High above, stretched out along the bluff in front of the Tennessee city, were thousands of spectators. Their cheers turned to wails as the Confederate fleet was smashed to pieces. “Never was a success so complete and so cheaply purchased by the victors; never an enemy so humiliated,” Vizetelly wrote in jubilation. “The stars and bars have been trailed in the dust … verily the Memphians have eaten dirt.”

32

However, when the readers of the

Illustrated London News

next heard from their war correspondent, Vizetelly was suffering from a crisis of conscience. “Your readers must understand that I never saw anything of Southern people until I landed at Memphis,” he wrote. “A ‘peculiar institution’ of theirs had prejudiced me somewhat against them, and I believed from all I heard that the Secession movement was but skin deep after all.” But “in Memphis and its immediate neighbourhood I made it my business to mix with all classes and test their loyalty or disloyalty … all were clamouring for separation. If then, such are the sentiments of the entire South, and defeat does not bring them nearer to the Union, what is to be the result of all this bloodshed?”

33

For the first time he questioned whether he had been supporting the right side.

Vizetelly was not the only Englishman to undergo a change of heart in June. Henry Morton Stanley, formerly of the Confederate Dixie Grays, joined the Union army on June 7. Stanley had been sent to Camp Douglas, outside Chicago, along with hundreds of other Confederate prisoners.

34

About twenty-six thousand men were sent there during the war; at least six thousand never came out. The inmates called it “80 acres of hell.” “The appearance of the prisoners startled me,” Stanley recalled. Every man was filthy, emaciated, and crawling with vermin.

35

To reach the latrines Stanley was forced to step over half-naked men lying in great puddles of feces, either too weak or too delirious to move. “Exhumed corpses could not have presented anything more hideous than dozens of these dead-and-alive men,” he wrote. “Every morning, the wagons came to the hospital and dead-house, to take away the bodies; and I saw the corpses rolled in their blankets, taken to the vehicles, and piled one upon another.”

36

Ill.21

Destruction of the Confederate “cottonclads” off Memphis, by Frank Vizetelly.

More than three hundred of the eight thousand prisoners in the camp claimed to be British subjects, and a group of them demanded to see the British consul, John Wilkins. He turned to Lord Lyons for advice. Surely, Wilkins asked, they should try to secure the release of those who had been forcibly conscripted into Confederate service. Lyons encouraged him to “exert all his influence unofficially in their favour,” but he deemed it hopeless to use official channels, since it would be impossible to prove whether a man had enlisted willingly.

37

Consul Wilkins argued and pleaded to see the British prisoners, but the authorities would not allow him inside the camp.

38

Stanley solved his predicament by switching sides and enlisting for three years in Battery L of the 1st Illinois Light Artillery. The “increase in sickness, the horrors of the prison, the oily atmosphere, the ignominious cartage of the dead, the useless flight of time, the fear of being incarcerated for years … so affected my spirits that I felt a few more days of these scenes would drive me mad.” He had never cared about politics anyway: “There were no blackies in Wales.”

39

In mid-June the battery was shipped to Harpers Ferry in western Virginia, where Stanley was hospitalized for dysentery on the twenty-second. Soon afterward, he went for a stroll around the hospital grounds and did not return. He went home to Wales, eager to get as far away from the war as possible.

Stanley was lucky not to have been assigned to Battery K, which was sent to Tennessee to help Union general George W. Morgan seize the Cumberland Gap from Confederate control. The Gap was a mountain pass through the Appalachians, where Virginia rubbed borders with neighboring Kentucky and Tennessee. The rugged Cumberland Mountains suddenly parted there, as though a spade had dug a thousand-foot-deep slice through the rock, allowing the aptly named Wilderness Road to wind its way down to the rich basin known as the Bluegrass region. General Morgan realized that the Confederate stronghold could not be taken by a direct attack. The only option was to split up his brigades and have them clamber up and over the Cumberland Mountains along mule tracks so they could launch a surprise assault on the Confederates from the other side.

Colonel Fitzroy De Courcy was ordered to lead his brigade through a steep gorge flanked by sheer rock on one side and the Cumberland River on the other. It had been eight months since he had been given command of the 16th Ohio Volunteers. His men were pleased to have one of the best drillmasters in the Union as their colonel. But the ways of the British Army were not those of a volunteer regiment, and the Ohioans considered him unduly harsh and exacting. He was no more popular with them than he had been with Fanny Seward. De Courcy was at his best when commanding larger forces in which individuals were less likely to be the victims of his scathing comments. But General Morgan had realized that a soldier of De Courcy’s experience was invaluable and had promoted him to brigade commander.

The trek took more than two weeks and cost De Courcy many of his horses and all his supply wagons, which either broke or became lodged in the rocks. The brigades were weary and hungry when they reunited on the other side of the Gap on June 18. The next day, they discovered that the terrible odyssey had been for nothing. The Confederates, believing that General Morgan possessed a force of more than fifty thousand, had abandoned the Gap.

40

Nevertheless, Morgan became emotional when he reflected on the hardships endured by De Courcy’s troops. “Pardon me for speaking of the heroic bearing and fortitude of the Seventh Division,” he wrote to General Buell and Secretary Stanton. “A nobler band never marched beneath a conquering flag.” He singled out De Courcy in particular and asked that he be promoted to brigadier general. “He is an accomplished officer and is every inch a soldier.” His request was ignored.

—

McClellan’s peninsula campaign to capture Richmond was already under way by June 20, although not in the manner expected by the War Department. McClellan was laying elaborate sieges to Yorktown (where a British army had surrendered in 1781) and Williamsburg, towns that the three British military observers with him believed could have been taken with a bit of dash and very little fuss. They held their tongues, though, and whenever anyone asked them for their opinion they confined themselves to praising the general’s wonderful job in transforming civilians into soldiers. This was exactly what Lord Palmerston wanted. He later reminded Lord Russell that all officers observing “federal forces in the field … should be Strictly cautioned not to make any Criticisms which might be useful to the Federals in pointing out to them Faults or Imperfections.… The Federals are luckily too vain to attach much value to the opinions of Englishmen, but our officers might be told to open their Eyes and Ears and to keep their mouths Shut.”

11.2

41

A combination of poor intelligence gathering and McClellan’s own paranoia had led him to believe that he was heavily outnumbered by the Confederates defending Richmond. His demands for reinforcements brought about the deployment of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry, known as the Cavaliers, which had been left behind to guard Washington. The morale of the regiment had improved since the arrival of Sir Percy Wyndham, a twenty-nine-year-old English soldier of fortune, on February 19, who had been assigned as its colonel by the War Department in an attempt to resolve the regiment’s officer problems. Few men would willingly have accepted such an unhappy outfit, but Sir Percy was not the reflective kind. In the words of one officer, “he strode along with the nonchalant air of one who had wooed Dame Fortune too long to be cast down by her frowns.”

42

The regiment found Sir Percy’s eccentricities rather endearing. Dark hair crowned his head in a Byronic wave, and a mustache and beard extended from his lips like bushy Christmas trees. He seemed to love dressing up and would change his uniform on the flimsiest of excuses. He looked younger than his years even though he had been a soldier since the age of fifteen and had served in the French, Austrian, and British armies. Wyndham’s parentage was dubious and his knighthood Italian (bestowed upon him by King Victor Emmanuel for his services during Garibaldi’s campaign), but his skills and bravery were authentic.

43

Although he dressed like a dandy, he possessed a temper that terrified the men. When enraged—which was apparent by the way he twiddled his mustache—Sir Percy was capable of anything, so much so that officers from other regiments insisted on wearing sidearms when around him. The men learned how to drill because if one person made a mistake, he would force the entire regiment to keep repeating the maneuver until they dropped from fatigue. But instead of hating him, the soldiers felt an extraordinary sense of pride. “Under our new Colonel our affairs have improved so much that we consider ourselves equal to almost any Cavalry Regiment in the field,” wrote its surgeon.

44