A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (48 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

10.1

William Yancey arrived back in New Orleans thoroughly disheartened by his mission. Cotton was a false god, he announced to the crowd that had gathered to greet him. The Queen favored the North, and Lord Palmerston was not interested in aiding the South. “Gladstone we can manage, but the feeling against slavery in England is so strong that no public man there dares extend a hand to help us. We have got to fight the Washington Government alone.”

2

10.2

One of the biggest areas of contention between Lyons and Seward had recently been removed when the U.S. War Department assumed responsibility for political arrests. “I think it is well that the arrests should be withdrawn from Seward,” Lord Lyons had written on February 18; “he certainly took delight in making them, and, I may say, playing with the whole matter. He is not at all a cruel or vindictive man, but he likes all things which make him feel that he has power.”

ELEVEN

Five Miles from Richmond

Shiloh—Fall of the Crescent City—The “Woman Order”—Vizetelly’s change of heart—The Seven Days’ Battles—“Percy, old boy!”—Lord Edward is duped—General Lee takes the field—McClellan retreats—“This is Butler’s doing”

L

yons and Seward were quietly congratulating each other over the success of the slave trade treaty when the North won its first major military victory of the war on April 7, 1862, at the Battle of Shiloh. The battle, which took place on Tennessee’s southern border, was a first on several counts. It was the first time Americans witnessed the mass slaughter that comes with large-scale combat. It was also the first intimation that no single battle, no matter how terrible, would end the war; and for young Henry Morton Stanley of the Dixie Grays, it was “the first time that Glory sickened me with its repulsive aspect, and made me suspect it was a glittering lie.”

1

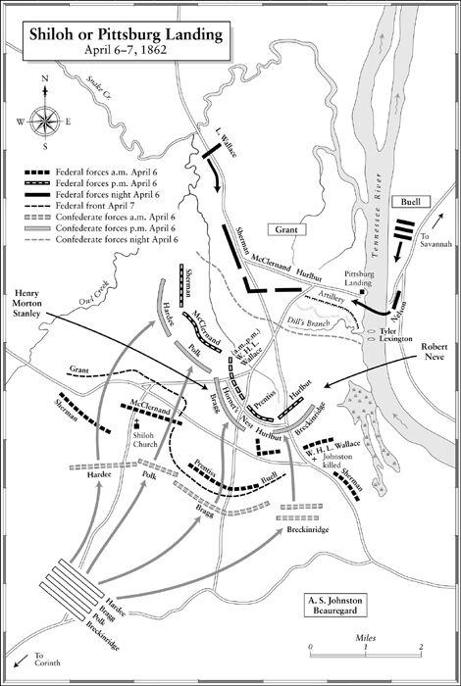

More than a hundred thousand soldiers fought in the two-day battle. Stanley’s side was led by General Albert Sidney Johnston—who was regarded by his Northern opponents as the ablest general in the Confederacy—and by Confederate general P.G.T. Beauregard, the hero of Fort Sumter and Bull Run. They had hoped to launch a surprise attack against General Grant while he rested his army of forty thousand men along the wooded ravines of the Tennessee River at Pittsburg Landing. “Shiloh,” which means “place of peace” in Hebrew, was a small Methodist church where Brigadier General William T. Sherman’s division had set up camp.

Map.8

Shiloh or Pittsburg Landing, April 6–7, 1862

Click

here

to view a larger image.

Johnston had chosen to attack Grant at Pittsburg Landing because he knew that an additional 25,000 reinforcements under General Don Carlos Buell were coming from Nashville. Once the two armies combined, Grant’s numerical superiority would be overwhelming, and Johnston had no doubt that capturing the strategic railroad junctions at Corinth, which was only twenty-two miles from Pittsburg Landing, would be their next object. Johnston’s own army was 44,000 strong, but he hoped that General Van Dorn and the survivors of Pea Ridge would arrive in time to give him additional support.

The plan, drawn up by Beauregard, was modeled on Napoleon’s strategy during the Waterloo campaign, where he had divided his forces to pick off the allies one by one. Historic plans rarely translate well, and those of the defeated even less so; yet the first day of the battle, April 6, began promisingly for the Confederates. Grant was taken by surprise. Sherman’s troops were sitting by their tents eating their breakfast in the warm morning sun when the rebels came yelling and whooping out of the woods. “Stand by, Gentlemen,” Stanley’s captain had ordered while they gathered in formation. The boy standing next to Stanley stopped down to pick a small posy of violets. “They are a sign of peace,” he told Stanley. “Perhaps they won’t shoot me if they see me wearing such flowers.” Impulsively, Stanley also stuck a sprig in his cap. Once they charged, “We had no individuality at this moment.… My nerves tingled, my pulses beat double quick, my heart throbbed loudly, and almost painfully,” Stanley recalled. The rebel yell jerked him out of his fear. “The wave after wave of human voices, louder than all other battle-sounds together, penetrated to every sense.” He remembered he was not alone but surrounded by four hundred other companies. “I rejoiced in the shouting like the rest.”

2

The Union soldiers had fled Shiloh by the time Stanley’s regiment arrived. The Confederates were stopped in their tracks by the sight of such abundance. Here was a neat little village of tents, many with a smoking stove in front, and all surrounded by mounds of new equipment. Everything was superior to their own camp, even the bedding. The sudden resumption of cannon fire recalled them to their senses, and the soldiers moved off. A short while later—whether it was five minutes or five hours Stanley did not know—he heard a piteous cry behind him. “Oh stop,

please

stop a bit.” He glanced back. It was the boy with the violets. He was standing awkwardly on one leg, staring at the remains of his foot.

3

Henry Stanley continued to run until something hit his belt buckle with such force that he flipped over and landed on the ground headfirst. When he came to, his regiment had disappeared and all was silent.

As he stumbled through the forest, he almost fell again, tripping over a body lying faceup. The eyes of the dead soldier seemed to stare back at him. With a shock, Stanley recognized him as the “stout English Sergeant of a neighbouring company.… This plump, ruddy-faced man had been conspicuous for his complexion, jovial features and good humour.” The more he ran, the more bodies he encountered. The dead, he recalled, “lay thick as the sleepers in a London park on a Bank Holiday.” The rest of the day became a series of wordless images. By the time he found his company again only fifty men remained.

Johnston and Beauregard’s Waterloo strategy fell apart in an area known as the Hornet’s Nest, where a sunken road acted like a defensive trench for the Federal troops, enabling them to hold steady for six hours against dozens of Confederate assaults. General Johnston was killed leading the final charge. A bullet tore through an artery in his leg, causing him to bleed to death in minutes. The Union soldiers holding the nest surrendered at 5:30

P.M.,

but by then Grant had formed a new defensive line along the river. He had been driven back two miles, but his army was still intact. “We’ve had the devil’s own day, haven’t we?” remarked Sherman to Grant after the fighting stopped. “Yes,” he said, with a short, sharp puff of the cigar; “Lick ’em tomorrow, though.”

4

Grant always used simple language when he spoke. The forty-year-old general was a quiet, plain figure whose forcefulness and intelligence were cloaked behind an unassuming manner. Associates struggled to describe him: “He is rather under middle height, of a spare, strong build; light-brown hair, and short, light brown beard,” wrote an aide to General Meade. “His face has three expressions: deep thought, extreme determination; and great simplicity and calmness.” Unlike McClellan, Grant had never aspired to become an American Napoleon; he had not even intended to become a professional soldier. “A military life had no charms for me,” Grant wrote of his time at West Point, “and I had not the faintest idea of staying in the army even if I should be graduated, which I did not expect.” But Grant remained in the army for eleven years, fighting in the Mexican War of 1846–48 and spending the next six years on mindless garrison duty, developing and failing to conquer a drink habit. Although happily married to his wife, Julia, and a devoted father to their four children, Grant floundered in civilian life. One year he was reduced to pawning his watch to buy Christmas presents for the family. When the war broke out, Grant was working as a clerk in his father’s tannery in Galena, Illinois—a humble climb down for the former captain. Within six months of volunteering, however, Grant had risen from colonel to brigadier general and, in addition to his old nickname in the army of “Sam”—for his initials U. S. (Uncle Sam)—had acquired the new national nickname of “Unconditional Surrender Grant” because of the terms he had offered to the defeated Confederates at Fort Donelson.

5

Sherman’s short conversation with Grant on the night of the sixth was actually one of the first between them. Sherman had suffered a nervous breakdown during the autumn of 1861 and had only recently returned to duty. Sherman was the opposite of Grant in mannerisms: his tall, wiry frame was always moving, he gesticulated as he spoke, and he often worked himself up into an excitement during conversation. But in many ways the pattern of his life was similar to Grant’s: Sherman had also struggled in civilian life; he, too, loved his wife and adored his children; and he had also fought his own private battles of the mind. The latter forged an unbreakable bond between them. Sherman later remarked: “Grant stood by me when I was crazy and I stood by him when he was drunk. And now we stand by each other always.” In turn, Grant said of him: “Sherman is impetuous, faulty but he sees his faults as well as any man.” Both were realists, neither was an abolitionist, and each approached the task of warfare in the same relentless and dogged spirit. Sherman had briefly wondered if they should retreat on the sixth, until speaking to Grant reaffirmed his resolve.

During the night, General Buell and his reinforcements sailed down the river to Pittsburg Landing. By contrast, flooded roads and a damaged rail system meant that Van Dorn’s battle-ravaged army was still sitting 250 miles away in Little Rock, Arkansas. This was good news for William Watson and the 3rd Louisiana Regiment, who were spared the fight, but it was a disaster for Beauregard. The weather turned, and a harsh downpour pelted the living and the dead. Flashes of lightning revealed the presence of wild pigs, attracted by the smell of fresh meat. Neither side had expected such a high number of casualties, and many of the ten thousand wounded were left out on the field all night, their screams so terrible that a Confederate soldier wrote, “This night of horrors will haunt me to my grave.”

6

For many of the reinforcements, including an Englishman named Robert Neve of the 5th Kentucky Volunteers, this was their baptism of war. “Boys,” said Neve’s commander in the morning, just before sending the Union regiment off into the woods, “we shall beat them today, for their general is killed. He was shot yesterday in leading a charge.” The news had no real meaning for Neve except that his side was apparently doing better than the rebels. Yesterday the Confederates had attacked; today it was their job to return the favor. Neve’s regiment surged through the woods like hunters flushing out their prey. Occasionally, a stray shell interrupted their momentum. With every foothold gained, Neve’s confidence rose; fighting was not so bad after all.

The exhausted Confederates made a game effort to repel the invaders. Henry Morton Stanley’s company marched forward in skirmishing order. The young soldier stood in a daze until his captain barked, “Now, Mr. Stanley, if you please,” which mortified him. He rushed blindly forward, straight into a pocket of Federal soldiers from Ohio. Two of them wanted to shoot him immediately, but an officer saved his life. As he was marched off to the Union camp, they chatted about “our respective causes, and, though I could not admit it,” he wrote later, “there was much reason in what they said.” The slavery question “could have been settled in another and quieter way, but they cared all their lives were worth for their country.”

7

General Beauregard ordered his army to retreat to Corinth, more than twenty miles away. In the confusion after the battle, along with the abandoned wagons and artillery guns that had become stuck in the mud, hundreds of wounded men were also left behind. Beauregard’s reputation for tactical genius was also a casualty, although Grant’s received a knock, too, for the way he was taken unawares on the first day. The total number of casualties was staggering: more than 23,000 men, or 25 percent of the forces engaged.

Shiloh was not the only blow to the Confederacy. That same day, the famously abrasive and arrogant Union commander General John Pope captured another strategic point: Island No. 10 on the Kentucky-Tennessee border. Journalist Edward Dicey had traveled west to Cairo, a commercial depot on the Mississippi River just above the Mason-Dixon Line. He watched as great hospital steamboats disgorged their wounded from Shiloh and Island No. 10. “All day and all night long you heard the ringing of their bells and the whistling of the steam.” Piles of coffins waited on the jetty “with the dead men’s names inscribed upon them, left standing in front of the railway offices.”

8