A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (122 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Feilden was so accustomed to keeping up a positive front for Julia that a general vagueness was creeping into all his letters. He gave his family every pertinent detail about his fiancée except her surname, and Lady Feilden was obliged to send an engagement present of gloves and a parasol addressed simply to Miss Julia. Feilden laughingly reassured Julia that the omission had not been for want of love. His feelings for her would never alter, he promised, nor would he ever give her a moment’s distress by flirting or looking at another woman: “My wife will never be afraid of my misbehaving in that manner,” he wrote firmly.

23

Feilden’s steadfast nature was one of the qualities that endeared him to his superiors. He had never complained about the state of headquarters even though his commanding officer, General Roswell S. Ripley, was a drunk and his staff not much better. It was nevertheless a great relief to him when Ripley was replaced at the beginning of October. “General Beauregard has recommended that Col. Harris be promoted to the rank of Major General, and that the defence of Charleston be handed over to him,” Feilden wrote excitedly to Julia. The change in command almost certainly guaranteed his promotion:

Col. [D. B.] Harris told me that he had told General Beauregard that he would only accept the command under certain conditions, and one of them was that he should select his own staff, and not have Ripley’s crowd palmed off on him. In that case he will apply for me as his AA General. It will be a capital thing for me if all this happens; it will give me my promotion to a Majority and put me in a position where I shall not be ranked by every ignoramus who has got influence enough to be placed on the staff of the Department of SC., Ga., & Fla. Colonel Harris is a splendid officer and just the man I should like to serve under. Charleston, with him in command, would make a splendid fight.

24

Feilden’s belief in the South was unshaken by the recent downturn in her fortunes. “I was intended to live in the midst of all these troubles,” he wrote, “for I can keep up my spirits under all circumstances.” True to form, his subsequent letters were all about their wedding.

25

But the flow of letters between Charleston and Greenville ceased in early October. Yellow fever had spread to the staff headquarters, and Colonel Harris was among the first to be struck with the disease. Feilden nursed him day and night for a week, but Harris was beyond help and died on October 10. Feilden stayed up for two nights, guarding the body from the depredations of rats and dogs until Harris’s family could claim the body. He had lost not only a friend but also his best chance of promotion.

General Beauregard’s choice to replace Harris was Lieutenant General William J. Hardee, a veteran of the Mexican War and the author of a drill manual used by both armies. Hardee had been looking for a new post since falling out with General Hood in Georgia, and he came with his own staff of trusted and experienced officers. Feilden’s friends were determined to ensure that Hardee realized he was gaining an officer of exceptional quality. Colonel Thomas Jordan, Beauregard’s chief of staff, wrote to General Hardee about Feilden on October 12: “He is of English birth and education and has seen service in the British Army. At first he was on inspection duty, but I had him transferred to my office, where he became my right-hand man—and I can recommend him as a judicious, well-informed, well trained staff officer.”

26

The letter languished in Hardee’s “to consider” pile. The general was appalled by the bedraggled state of his new troops and immediately launched a campaign for supplies. The soldiers lacked blankets and coats; “very many of my men are absolutely barefooted,” he complained to Richmond on October 19.

Francis Lawley had seen for himself the weakened state of the Southern armies. It went against the grain with him to dwell on the Confederacy’s deprivations, but he could no longer ignore the truth. “I cannot be blind to the fact, as I meet officers and privates from General Lee’s army,” he wrote to Lord Wharncliffe from Richmond on October 12, “that they are half worn out, and that, though the spirit is the same as ever, they urgently need rest.” Their diet for the past 160 days had consisted of bread and salted meat, while the enemy had at its command “all that lavish profusion of expenditure and the scientific experience that the whole civilized world can contribute.”

27

However, when Lawley praised “the patience and self-denying endurance of the troops,” he was stretching an ideal already abandoned by his friends. Earlier in the week, the chief of ordnance, General Josiah Gorgas, had privately conceded that the soldiers’ spirits were almost beyond saving: “Our poor harrowed and overworked soldiers are getting worn out with the campaign. They see nothing before them but certain death, and have, I fear, fallen into a sort of hopelessness, and are dispirited. Certain it is that they do not fight as they fought at the Wilderness and Spotsylvania.”

28

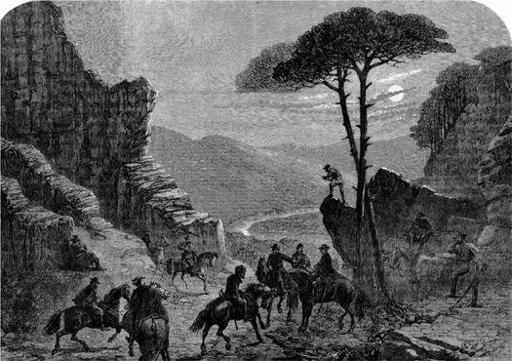

Ill.55

Rendezvous of General Mosby’s men above the Shenandoah Valley, by Frank Vizetelly.

Frank Vizetelly witnessed the battles between Jubal Early’s similarly exhausted Confederates and Sheridan’s hard-driving cavalry in the Shenandoah Valley. Early was relying on the help of John Singleton Mosby and his Partisan Rangers to harass the Federals, and at first Vizetelly was dazzled by Mosby, whose guerrilla raids reminded him of the daredevil spirit of Jeb Stuart. “His achievements are perfectly marvellous,” wrote Vizetelly after hearing how the Rangers swooped down on a six-hundred-foot-long Federal wagon train in mid-August and captured the entire contents, suffering only two casualties in the raid.

29

Mosby had been able to outlast his former rival Sir Percy Wyndham, but his new opponent, the English colonel L.D.H. Currie, could not be tricked into making the sort of mistakes that had been Wyndham’s undoing. Although Currie could not prevent Mosby’s raids, he kept the wagon trains moving and intact. Nor were the raiders much help to Jubal Early in a real cavalry battle. Early had lost an entire brigade in a combined Union cavalry and artillery attack on September 24.

33.4

Since then, he had been able to mount only insignificant skirmishes against Sheridan, who was carrying out Grant’s order to lay waste to the region. Vizetelly had covered many campaigns, but none that so explicitly targeted the enemy’s will to fight. The sight of emaciated women pleading with soldiers for bread to feed their children led him to accuse Union troops of deliberately causing mass starvation among the civilians. Sheridan’s declaration that “the people must be left nothing but their eyes to weep with over the war” was repeated many times in the British press. This sort of “wanton destructiveness,” asserted the editor of the

Illustrated London News,

is “unknown to modern warfare.”

33.5

30

There was nowhere safe for refugees anymore: families who thought they would find sanctuary in Richmond risked losing their adolescent sons to the Confederate army. Despite President Davis’s dictum against “grinding the seed corn of the Republic,” boys as young as fifteen were now being rounded up and marched to the trenches. “No wonder there are many deserters—no wonder men become indifferent as to which side shall prevail,” wrote the War Department clerk John Jones bitterly.

31

Nevertheless, those who risked the journey to Richmond sometimes met with surprising generosity. “Virginians of the real old stock,” in Mary Sophia Hill’s words, gave her a corner to sleep in when she arrived ill and penniless in early October. The military tribunal in New Orleans had returned a guilty verdict with the recommendation of imprisonment for the duration of the war. But her defense lawyer, a “Union man” named Christian Roselius, had protested against the sentence and won a commutation to banishment from New Orleans. Consul Coppell also interceded on her behalf, offering to buy passage for Mary on the

Sir William Peel,

which was about to depart for England, but General Banks refused, saying, “She will have to run the blockade. She will have plenty of trouble; perhaps it will teach her to behave herself the rest of her days.”

32

“He had his desire,” recalled Mary. “I did have plenty of trouble.” Despite the insistence of the new legation secretary, Joseph Burnley, that “everything that could be done in this matter has been done,” Mary was carried across the picket lines into Confederate territory and left by the road to fend for herself.

33

Mary never revealed how she made the one-thousand-mile journey from New Orleans to Richmond without a horse or money, but the memory would forever haunt her, driving her to seek justice years after the war.

—

Mary had arrived in Richmond shortly after the Federals captured another of the forts guarding the approach to the capital on September 29. The enemy, wrote John Jones on October 4, “is now within five miles of the city, and if his progress is not checked, he will soon be throwing shells at us.… Flour rose yesterday to $425 a barrel, meal to $72 a bushel.”

34

Mary risked her life to look for her twin brother, Sam, who had been sent to the trenches with the other engineers in his office. While crossing a pontoon bridge she stood aside to allow General Lee to ride past. “I consider it an honor,” she wrote, “and a great one too, to have seen the General of the age, Robert E. Lee, the soldier’s friend, the Christian warrior.”

35

Lee had grown used to such hero worship; his determination to endure the same hardships as his men was widely known, though it had not deterred Southerners, particularly women, from delivering food and gifts to his tent. But another side to Lee had become apparent of late. No man, not even the great “Christian warrior,” could withstand the relentless attrition of troops, supplies, and options without showing the strain. Francis Dawson was taken to Lee’s mess and subjected to a tirade of sarcastic remarks:

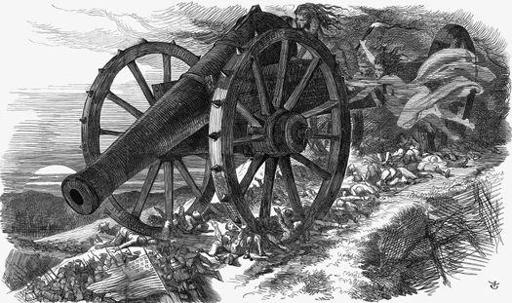

Ill.56

Punch’s terrifying depiction of the human cost of the Civil War, September 1864.

It was the most uncomfortable meal that I ever had in my life [he wrote]. My frame of mind can be imagined when General Lee spoke to me in this way: “Mr. Dawson will you take some of this bacon? I fear that it is not very good, but I trust that you will excuse that. John! Give Mr. Dawson some water; I pray pardon me for giving you this cup. Our table service is not as complete as it should be. May I give you some bread? I fear it is not well baked, but I hope you will not mind that.” Etc., etc., etc.; while my cheeks were red and my ears were tingling, and I wished myself anywhere else than at General Lee’s headquarters.

36

Only a month of fighting weather remained. On October 7, 1864, Lee ordered his final large-scale assault of the year, sending two divisions along Darbytown Road with orders to flush the Federals out of their new position. They started off well and overran the first line of trenches, capturing more than three hundred soldiers in the process, among them the English fugitive Robert Livingstone, who had been released from the hospital on September 30 and had only rejoined the 3rd New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry the day before. As Livingstone was marched away, he could hear his side responding with a massive barrage of fire. The Confederates were faltering. Lee galloped toward the retreaters, waving his hat and shouting for them to make another stand. On previous occasions the very sight of him had been enough to stem a flight, but this time the men continued to run.