A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (59 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Dawson could not rejoin Longstreet’s army until his exchange was official, which would not be until the end of November, but he was able to wangle a military pass from Colonel Gorgas, who recognized that the foreign volunteer could simply resign if he became fed up. Dawson left the city to visit the Pegrams. Though he did not like to admit it, he was in love—in love with the South, with its people, its culture, and at this particular moment, with Miss Pegram. “You will think me partial, but it is not so,” Dawson insisted in a letter to his mother. Yet he could not help dwelling on certain attributes of Captain Pegram’s niece: “Loving brown eyes, perfect hands and a rich mass of glorious auburn hair.”

42

The delightful Miss Pegram had nursed him during his convalescence in the summer, and was pleased to do so again.

Dawson’s departure from Richmond at the beginning of October coincided with the arrival of Francis Lawley and Lieutenant Colonel Garnet Wolseley. They had met in Baltimore shortly before the Battle of Antietam when they were trying to slip into the Confederacy, the former to report for

The Times,

the latter, who was stationed in Canada, to satisfy his curiosity about volunteer armies. The twenty-nine-year-old Wolseley had been among the first wave of soldiers sent out by the British government during the

Trent

affair. After the possibility of war had subsided, Wolseley continued to be fascinated by the events south of the border. “It is not easy to describe the breathless interest and excitement with which from month to month, almost from day to day, we English soldiers read and studied every report that could be obtained of the war as it proceeded,” he wrote later. Wolseley badgered his superiors until he and a friend secured a two-month leave of absence.

43

They then flipped a coin to decide who would go to the North and who would have the harder task of going to the South. Wolseley “won” the South.

44

During the summer,

The Times

had offered Lawley the now vacant post of special correspondent. The middling poet and bon vivant Charles Mackay had replaced J. C. Bancroft Davis in New York and was supplying the paper with business and political analysis.

13.2

But Delane needed the eyewitness reports previously supplied by Russell. Lawley knew nothing about military matters, but in two other important respects he had changed a great deal since February. He was a hardier traveler, and he had decided that the South had a right to independence. No single event was responsible for Lawley’s apostasy, but the Anglophobia displayed before and during the

Trent

affair, not to mention the untrammeled hounding of his friend William Howard Russell, had helped to convince him that a strong Confederacy was essential if the North’s aggressive tendencies were to be restrained.

45

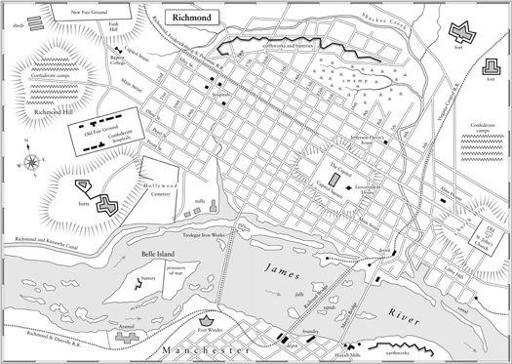

Map.12

Richmond

Click

here

to view a larger image.

Just surviving the tortuous journey past Federal pickets and scouting parties into Confederate territory was an education for Lawley. W. W. Glenn’s contacts were finding it harder to slip back and forth. Lawley had never before shared a room, let alone a bed, with several dirty strangers. In his autobiography, Field Marshal Viscount Wolseley, as he was to become, recalled with amusement being woken up in the middle of the night by Lawley, who was standing in the corner of the farmer’s shed where they were sleeping, frantically waving his stick at the rats scurrying over his feet. Less comical was their train ride from Fredericksburg to Richmond. The travelers had to squeeze in beside hundreds of amputees who were being conveyed to hospitals in the city. The men lay stretched across the seats and were bumped and jolted continuously. “That train,” wrote Wolseley, “opened Frank Lawley’s eyes to the horrible side of war, made all the more in this instance because no chloroform or medical supplies of any sort were available.”

46

When Lawley and Wolseley reached Richmond, they were lucky to secure an attic room in the Exchange Hotel. Frank Vizetelly, they learned, had snagged the last remaining bed at the Spotswood, the Willard’s of Richmond. He was glad of their company and went with them to the war secretary’s office to obtain a travel pass. The sight of the captured flags of the enemy lying in heaps on the floor shocked Wolseley, but he held his tongue while they received their papers and letters of introduction. The following day, October 9, the little party set off to find General Lee’s headquarters.

Wolseley came away with fragmentary but vivid impressions of the city. Richmond had hardly changed since Charles Dickens had described it in 1842 as “delightfully situated on eight hills, overhanging the James River.” It was still a city of churches rather than saloons, and despite the arrival of five railway lines over the past thirty years, the pace of life remained slow and decorous. The residents prized the city’s reputation as the premier cultural center of the South. Richmond boasted five daily newspapers, a literary journal, several theaters, and an academy of fine arts. The city did share one characteristic with Washington: its hotels were similarly uncomfortable and dirty. But otherwise the capitals were a study in contrasts. Washington was a city built to order, lacking in history or tradition; Richmond was formed shortly after the first settlers arrived in Jamestown, and its history was indistinguishable from many of the most famous events of the Revolutionary era. Patrick Henry’s “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” speech in 1775 was made in St. John’s church on Broad Street.

Unlike the domeless Capitol building in Washington, Richmond’s neoclassical capitol was not only finished but also widely admired and imitated. Designed by Thomas Jefferson, it stood proudly on the highest hill of the city, within a twelve-acre park called Capitol Square, dominating the skyline like the Parthenon on the Acropolis. Here, in a cluster of classical buildings, lay the seat of the Confederate government. The Confederate presidential residence was situated four blocks away, in an Italianate mansion that had been donated to the government by the owner.

Richmond was built on a rising slope, and its streets were regular and easy to navigate. The industrial district—the flour mills, tobacco and wheat processing plants, and ironworks—was down by the river. Shops and businesses of the better class were below Capitol Square, along Main Street, and the residential neighborhoods were on the crests of the hills. The city’s busiest slave auction house, owned by Robert Lumpkin, was only three blocks from the capitol. Wolseley avoided it when he went exploring, though it was almost the only establishment in town with goods to sell. The bookshops were empty of books, and the general stores were denuded of everyday items like shoe polish and pins.

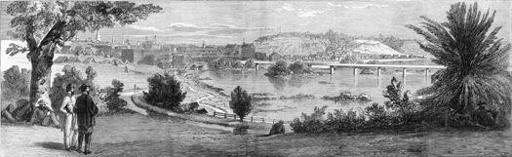

Ill.23

View of Richmond from the west, by Frank Vizetelly, who sketched his own image on the left, under the tree.

Before they left, Lawley gave his

Times

dispatch to the French consul, who was less of a stickler than Consul Moore when it came to preserving the sanctity of the diplomatic bag. Like Wolseley, Lawley had noticed the effects of the blockade, but he airily dismissed them in his article as merely depriving Southerners of a few unnecessary luxuries. Nor did it matter, he declared, that Confederate soldiers often had to march without shoes, hats, or coats: “These men, many of them bearing some of England’s most honoured names, and descended from England’s best families, are in the field, and have been so for 19 months, fighting against [Northern] mercenaries!” (The article prompted the paper’s managing editor, Mowbray Morris, to remind Lawley that they required his newsgathering skills, rather than his opinions, since they had plenty of the latter at home.)

47

Had he read the dispatch, Consul Moore would have been infuriated by Lawley’s insouciance. The beleaguered diplomat was, at this moment, writing pathetic letters to the Foreign Office saying he was wretchedly understaffed, overwhelmed, and unable to buy even such commodities as coal for the office: “I leave it to your Lordship to judge if we are not entitled to extra aid.”

48

Lawley had never had to suffer a moment’s hardship that was not the direct result of his own profligacy. Perhaps this was why he came to idolize the Confederate army. The young plantation aristocrats who so readily sacrificed everything for the sake of an ideal put his own idle existence to shame. Many of them, like the ambulance driver who conveyed Lawley and his friends away from Richmond, were utterly unsuited for soldiering. The driver, the son of a wealthy farmer, had accepted the relatively menial occupation because his battle wounds were too severe to allow him to continue to fight. Yet he had no idea how to look after himself, even to the extent of becoming drenched because he had never had to fetch his own blanket before.

49

Observing the Southerner’s inability to shift for himself, Wolseley decided that the difference between a professional army and a collection of armed volunteers was, for want of a better term, the existence of esprit de corps. Without it, as he and other English observers noticed, nothing worked as it should.

50

There appeared to be little internal cooperation or forward thinking. Regiments would march along muddy roads, making them worse, without stopping to lay new tracks so that the next regiment would not become bogged down. Wolseley admitted to feeling “sorely puzzled” about the South. Slaves were referred to as “servants,” and white servants as “the help,” but the euphemisms were simply window-dressing the obvious. Its people combined genteel manners with ancient barbarism; they were brave in the face of appalling deprivation, and personally charming even when proclaiming their bitterness at being betrayed by their British cousins.

51

As the three Englishmen traveled to General Lee’s headquarters near Winchester, they were treated to the full glory of Virginia in the autumn, the gentle golden light reminding Wolseley of a country scene from a Claude painting.

52

When they arrived at Lee’s camp in the Shenandoah Valley in mid-October, Wolseley and Lawley were surprised by its spartan appearance. The headquarters was nothing more than eight pole tents placed in a row on hard, rocky ground. Horses roamed loose, wagons were pitched willy-nilly and were clearly serving as makeshift beds for some of the officers.

Lee himself inspired a strong reaction in the travelers; Wolseley developed an immediate case of hero worship. Though still recovering the use of his hands, the Confederate general was a “splendid specimen of an English gentleman, with one of the most rarely handsome faces I ever saw.… You only have to be in his society for a very brief period to be convinced that whatever he says may be implicitly relied upon.” Wolseley recognized in Lee a military genius: “I never felt my own individual insignificance more keenly than I did in his presence.”

53

Lawley was equally enthusiastic. Lee was “impressive and imposing,” he wrote, “his dark brown eyes remarkably direct and honest as they meet you fully and firmly.… It is certain that General Lee has no superior in the Confederacy and it may be doubted whether he has any equal.”

54

Vizetelly quickly set about sketching a portrait of him for English readers while Lee conversed with the visitors. Not once, Lawley and Wolseley observed, did the general express any bitterness toward the North, even though his homes had been pillaged without restraint. Nor did Lee discuss the recent battle at Antietam.