A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (60 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Unable to spare even a single tent for the travelers, Lee gave them a two-horse wagon so that they would be able to visit the camps of the other generals. “Upon leaving him,” wrote Wolseley, “we drove to Bunker’s Hill … at which place Stonewall Jackson, now of world-wide celebrity, had his headquarters.” The normally taciturn Jackson made a particular effort with his guests, and even reminisced about his time in England, leading them to think that his reputation for moroseness was rather overblown. Indeed, the general talked so much that the three visitors never had the chance to ask him anything. “As we rode away,” wrote the Confederate officer escorting the group, “I said: ‘Gentlemen, you have disclosed Jackson in a new character to me, and I’ve been carefully observing him for a year and a half. You have made him exhibit

finesse,

for he did all the talking to keep you from asking too curious or embarrassing questions. I never saw anything like it in him before.’ ”

55

Jackson’s ruse did not prevent the visitors from making their own judgments. Lawley noticed that the general had achieved a kind of mythical stature. Civilians flocked to his camp just for a glimpse of the great man; even his staff regarded him with reverence. The journalist thought it was dangerous that the hopes of so many should rest on just one commander. Yet he could understand why. Jackson lived the part. “Dressed in his grey uniform,” wrote Wolseley, “he looks the hero that he is.”

56

General Longstreet, their final stop on the tour, could only suffer by comparison to Lee and Jackson. Lawley, however, saw much to praise. “His frame is stout and heavy, his countenance florid and cheery, and eminently English in appearance.”

57

They watched a review of ten thousand of his soldiers. “Among this body there were no shoeless or barefooted sufferers,” wrote Lawley; “a finer or more spirited body of men has never been assembled together on the North American continent.” According to Wolseley, the boots and shoes had only recently arrived in a large shipment from England.

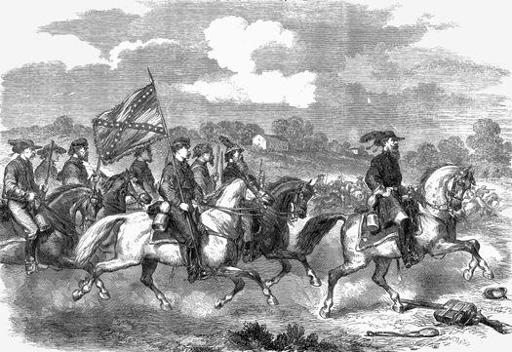

Wolseley’s leave was coming to an end and he had to begin his journey home. He was able to achieve only a brief glimpse of Lee’s cavalry commander, J.E.B. (“Jeb”) Stuart. The travelers arrived at his headquarters, an elegant plantation house called “The Bower,” to discover that the famed general was off on a raid in Pennsylvania. The Bower’s owners were still there, however, as were numerous pretty female relatives whose chief raison d’être appeared to be making the officers comfortable. Stuart returned on October 10 with twelve hundred captured horses and not a single man lost. Wolseley observed the riders galloping home and was impressed by their superiority to Northern cavalry, “who can scarcely sit on their horses, even when trotting.”

58

Francis Lawley and Frank Vizetelly were a great hit among Stuart’s staff. Lieutenant Colonel William Blackford recalled the officers’ delight when they returned to camp on October 16 and found the journalists waiting to meet them. “These gentlemen were often after this our guests, and we all became very fond of them,” he wrote. They already had a Prussian officer serving as a volunteer aide, Major Heros von Borcke, and were used to eccentric foreigners.

59

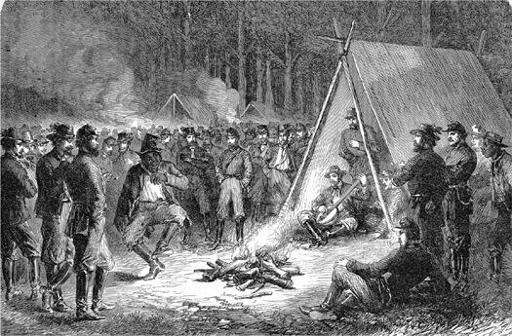

A partially recovered Henry MacIver was also pottering in and out of Stuart’s camp, trying to be useful but more often simply passing the time with friends from his Garibaldi days. He was delighted to see Vizetelly again. The hard-drinking journalist “was the most interesting narrator I have ever listened to around a campfire,” wrote Blackford.

Ill.24

General Jeb Stuart scouting in the neighborhood of Culpeper Court House, Virginia, by Frank Vizetelly.

There was not a disreputable or reputable place of prominence in the civilized world that he did not know all about.… We had a shrewd suspicion that he drew a little on his imagination for his facts, but what difference did that make to us. Late into the night we all sat around the embers of our fire out under the grand oaks listening to the fascinating tales he told, his expressive countenance and gestures giving full effect to his words by their play. Mr. Lawley was an exceedingly intelligent and refined Englishman and in another style we enjoyed his instructive conversation very much, but Vizetelly was fascinating.

60

Ill.25

Night amusements in the Confederate camp, by Frank Vizetelly.

Blackford and Borcke invited them to pitch their tents on the vacant plot next to their own. “Regularly after dinner,” Borcke recalled, “our whole family of officers, from the commander down to the youngest lieutenant, used to assemble in [Vizetelly’s] tent, squeezing ourselves into narrow quarters to hear his entertaining narratives.”

61

During the journey home, Wolseley mused on the scenes he had witnessed down south. He had seen many armies, “but I never saw one composed of finer men, or that looked more like

work,

” he wrote. “Any one who goes amongst those men in their bivouacs, and talks to them as I did, will soon learn why it is that their Generals laugh at the idea of Mr. Lincoln’s mercenaries subjugating the South.”

62

By the time he reached Montreal, he had made up his mind to campaign for Southern recognition. Wolseley was aware that the question remained open in Britain. Like so many Englishmen, he assumed that slavery would quickly die out after independence. The real moral issue, in his eyes, was how long the suffering should be allowed to continue. In a bid to reach the widest possible audience, he decided to write an essay for the literary

Blackwood’s Magazine

entitled “A Month’s Visit to the Confederate Headquarters.” “The first question always asked me by both men and women was,” he declared in the article, “why England had not recognised their independence.… Had we no feelings of sympathy for the descendants of our banished cavaliers? Was not blood thicker than water?”

63

13.1

Lincoln continued to be hamstrung by the opposition to emancipation from influential leaders such as John Hughes, the archbishop of New York, who had already issued this warning: “We Catholics … have not the slightest idea of carrying on a war that costs so much blood and treasure just to gratify a clique of Abolitionists in the North.” With elections coming up and the military tide against him, Lincoln felt that he could not afford to alienate anyone.

13.2

Mackay had been a foot soldier in the army of underpaid hacks until 1843, when, at the age of twenty-nine, he made his reputation with a book called

Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds.

But in his heart he always considered himself a poet rather than a journalist. He did not intend to do any traveling for

The Times.

Mackay had toured the United States in 1858 and felt that he had experienced enough trains and American hotels to last him a lifetime.

FOURTEEN

A Fateful Decision

British reaction to Antietam—Gladstone’s Newcastle speech—Battle in the cabinet—The emperor proposes joint intervention—Russell turns tail

B

ritain did not receive word of Antietam until the very end of September. “I hope more than I dare express,” wrote Adams in his diary on the twenty-ninth. “For a fortnight my mind has been running so strongly on all this night and day, that it seems to almost threaten my life.” His son Charles Francis Jr., now Lieutenant Adams in the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry, had last written to the family to say that his regiment was joining the Army of the Potomac in Maryland. The following day, on the thirtieth, the legation heard that Lee’s advance had been stopped. “But [McClellan] failed to follow it up and let them escape,” raged Benjamin Moran.

1

Adams was also disappointed. Nor were his fears allayed about his son. It was several more days before they received a letter from Charles Francis Jr. His regiment had sat on their horses in readiness while shells exploded on the surrounding hills, but McClellan never sent them into battle.

Reports of the terrific slaughter at Antietam shocked the nation; the 25,000 casualties on a single day seemed almost inconceivable, especially when compared to the 25,000 Britain suffered during the entire Crimean War.

2

“The Federals in their turn have had a victory; and so it goes on; when will it end? Fanny Kemble says not until the South is coerced back into the Union,” wrote Henry Greville, reflecting the horror felt by many people at the thought that the war might continue for many months more.

3

Five days later, on October 5, 1862, there was a second uproar in the press, this time over Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. As Seward had feared from the outset, the Proclamation was widely denounced as a cynical and desperate ploy. Charles Francis Adams understood its symbolic importance, but even pro-Northern supporters could not understand why Lincoln had allowed the border states to keep their slaves, unless the emancipation order was directed against the South rather than slavery itself. “Our people are very imperfectly acquainted with the powers of your Federal Government,” explained the antislavery crusader George Thompson to his American counterpart William Lloyd Garrison. “They know little or nothing of your constitution—its compromises, guarantees, limitations, obligations, etc. They are consequently unable to appreciate the difficulties of your president.”

4

The

Spectator

declared itself to be disappointed with the Proclamation: “The principle is not that a human being cannot justly own another,” it insisted, “but that he cannot own him unless he is loyal to the United States.”

5

For the radical Richard Cobden, the moral contradiction proved that “the leaders in the Federal government are not equal to the occasion.”

6

The Times

went further and accused Lincoln of inciting the slaves in the South to kill their owners, imagining in graphic terms how the president “will appeal to the black blood of the African; he will whisper of the pleasures of spoil and of the gratification of yet fiercer instincts; and when blood begins to flow and shrieks come piercing through the darkness, Mr. Lincoln will wait till the rising flames tell that all is consummated, and he will rub his hands and think that revenge is sweet.”

7