A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (57 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Whether or not Russell was “perfectly satisfied” before Second Bull Run, afterward he became a thorough convert to the idea that the war must be stopped. “I agree with you that the time is come for offering mediation to the United States Government, with a view to the recognition of the independence of the Confederates,” he wrote to Palmerston on September 17. “I agree further, that in case of failure, we ought ourselves to recognize the South States as an independent state.” Russell ordered their ambassador in Paris, Lord Cowley, to have a quiet word with the French foreign minister, Édouard Thouvenel, about cooperation from the emperor.

8

—

For the Confederates, Lee’s victory at Second Bull Run was the signal to begin creating a groundswell of public sympathy in favor of Southern recognition. In France, Confederate commissioner John Slidell had heard through intermediaries that the emperor would not state publicly that the Powers should intervene until he had received unambiguous reassurances from Britain that it would follow suit. Henry Hotze put his stable of writers to work. “Since one journalist usually writes for several publications,” he explained to the Confederate secretary of state, Judah P. Benjamin, “I have thus the opportunity of multiplying myself, so to speak, to an almost unlimited extent.” He was not worried about “the sympathies of the intelligent classes [which] are now intensified into a feeling of sincere admiration.” But James Spence’s failure to stir up unrest in the manufacturing districts made Hotze fear that the working classes were implacable enemies of the South. “I am convinced,” he admitted, “that the astonishing fortitude and patience with which they endure [the cotton famine] is mainly due to a consciousness that by any other course they would promote our interests.”

9

Hotze was overestimating his success with the “intelligent” classes and underestimating the unpopularity of the North among the workers. But what united all the classes in England, regardless of his efforts, was an ingrained hatred of slavery; the institution was an insurmountable stumbling block. Slidell and Mason could and did mislead potential Southern sympathizers when the occasion demanded. Camouflaging the South’s total dependence on slavery was the only way, for example, that Slidell was able to persuade the veteran abolition campaigner Lord Shaftesbury to give them his support. Slidell had targeted Shaftesbury because “his peculiar position as the leader of an extensive and influential class in England, and the son-in-law of Lady Palmerston gives a value and significance to his opinions beyond that of a simple member of the House of Lords,” he explained to Benjamin. But the relationship almost foundered in September when Shaftesbury asked him, in all innocence, “if the [Confederate] President could not in some way present the prospect of gradual emancipation. Such a declaration coming from him unsolicited would have the happiest effect in Europe.” Slidell circumvented the question by replying that abolition was an issue for the individual states to decide and he could not speak for all of them.

10

Slidell was grateful that Lincoln was still publicly maintaining an ambivalent stance on slavery.

11

On August 19, Lincoln declared in a letter published by the

New York Tribune,

“If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it.”

13.1

It enabled him to suggest to Lord Shaftesbury that the chances of emancipation “were much better if we were left to ourselves than if we had remained in the Union.”

12

Slidell heard from Shaftesbury that a decision regarding Southern recognition was “close at hand, a very few weeks at the furthest.” Ironically, of all the concerns that might delay or precipitate the decision, Palmerston and Russell never mentioned slavery or public opinion as being among them. They were far more worried that the North would simply reject Britain’s offer to mediate. The Duke of Argyll had warned Palmerston at the beginning of September that the Americans would never accept any interference from Europe. “I think it right to tell you of a letter we have had from Sumner,” wrote the duke on September 2. “He says that there is

no thought

of giving up the Contest. He speaks, indeed, as if doing so were simply impossible.” It would therefore “be folly, I think, to attempt any intervention.”

13

But there had been more momentous news from America since Russell and Palmerston had agreed to hold a cabinet meeting on the subject. General Lee had apparently marched with his Confederate army north into Maryland. “The two armies are approaching each other to the North of Washington and another great conflict is about to take place,” Palmerston wrote to Russell on September 22. “Any proposal for mediation or armistice would no doubt just now be refused by the Federals. [But] if they are thoroughly beaten … they may be brought to a more reasonable state of mind.”

14

Two days later, on the twenty-fourth, Palmerston informed a delighted Gladstone about the mediation plan. “The proposal would naturally be made to both North and South,” he wrote. “If both accepted we should recommend an Armistice and Cessation of Blockades with a View to Negotiation on the Basis of Separation.” If only the South accepted, “we should then, I conceive, acknowledge the Independence of the South.” Russell had suggested that the cabinet meeting should be held at the end of October, but Palmerston was now thinking it should be sooner. “A great battle appeared by the last accounts to be coming on … a few Days will bring us important accounts.”

15

—

Britain was waiting for news even as thousands of American families were already grieving after the single bloodiest day of the war. Forty-eight hours after his victory at Second Bull Run, Robert E. Lee had indeed ordered his Army of Northern Virginia to move north. On September 4, his exhausted and underfed troops traversed the Potomac River into the border state of Maryland. Lee’s plan was to reach Pennsylvania, cut the rail links there, and isolate Washington from the rest of the country. He understood as well as the Confederate government that Europe was waiting for a clear-cut victory, but this was not the reason behind his decision to invade the North. He hoped that the very presence of Confederate soldiers on Northern soil would give President Davis the authority to demand “of the United States the recognition of our independence.”

16

If that failed, Lee thought it would be a sufficient shock to the North to make the upcoming elections, which included several state governorships, turn in favor of the antiwar Democrats.

On September 12, Lincoln overruled his cabinet and reinstated General McClellan to lead the Army of the Potomac. The soldiers trusted Little Mac, as they called him, and Lincoln felt strongly that this was no time for Washington to play favorites. Among the 80,000 troops who chased after Lee were Ebenezer Wells of the 79th New York Highlanders and George Herbert of the 9th New York Zouaves. Five major battles and twelve engagements in eighteen months had drained the regiments of their lifeblood. In the words of one chronicler, the Highlanders had withered to a “body of cripples.”

17

Ebenezer Wells had been wounded during the Second Battle of Bull Run. “My Sargent said to me, Wells, leave the field,” he recalled. “I said what for, he pointed to my leg. I looked and saw blood, I soon felt where it came from: I had been shot in the side.… [In] the intense excitement of that minute I only remember of having felt a slight stitch.” He was well enough to join the exodus from Washington a week later. The knowledge that McClellan was again their leader “revived the spirits of the men and without any rest we marched into Maryland.” It was probably fortunate that McClellan preferred to move his army at a crawl rather than a jog. Once again, the general’s remarkably inefficient intelligence had magnified Lee’s forces to twice their actual size, causing McClellan to become hypercautious.

Ill fortune was, however, dogging Lee at every turn. His army should have had at least 15,000 more men, but many had straggled to the point of desertion or refused on principle to invade the North. Lee himself began the incursion with a nasty fall that left both his hands in splints. Generals Jackson and Longstreet also suffered minor but incapacitating injuries. All three had to be conveyed through Maryland in ambulances rather than gallantly leading their men on horseback. As the shoeless army tramped its way through the quiet countryside, it became clear that the Marylanders would not rise up or even offer breakfast to the Confederates. The men had to feed themselves with unripe apples and green corn snatched from the fields.

18

Lee naturally worried about his supply line. Aware that there were Federal forces behind him that could cut off his army, he decided that he would have to neutralize the threat they posed before he proceeded farther north. He would have to detach his small army into even smaller, autonomous divisions—a risky maneuver, but it had worked against Pope, and Lee believed that he had the initiative.

On September 13, the 27th Indiana Volunteers trailed into an abandoned Confederate camp outside Frederick. Four of them lay down on the grass to talk and rest in the late summer haze. One soldier, the future president of Oregon State University, noticed a yellow envelope lying in the field.

19

Inside, the group found three cigars and Lee’s detailed plans for the next four days. The document, entitled Special Orders 191, was speedily relayed up the chain of command to McClellan. Almost as quickly, a Confederate sympathizer galloped off to report the dreadful news. At first, McClellan believed the orders were a trick, but a captain from Indiana recognized the handwriting and could vouch that the copyist on Lee’s staff had been a friend before the war.

20

“I have all the plans of the rebels, and will catch them in their own trap,” McClellan telegraphed Lincoln. “Will send you trophies.”

21

McClellan delayed his move for two days, even though his 95,000-strong Army of the Potomac was facing a Confederate force of only 18,000. By September 16, Lee had managed to reunite two-thirds of his divided army and take up a position around a quiet Maryland village named Sharpsburg. About a mile away, on the other side of Antietam Creek, McClellan’s soldiers gathered in readiness. “Our Brigade stole into position about half-past 10 o’clock on the night of the 16th,” recalled a private in Company G of the 9th New York Volunteers. “No lights were permitted, and all conversation was carried on in whispers.” Their place in the line was inside a thin cornfield that sloped down toward a creek. They sat down on the plowed earth and watched dark moving masses in the distance. “There was something weirdly impressive yet unreal,” the private continued, “in the gradual drawing together of those whispering armies under cover of the night—something of awe and dread, as always in the secret preparation for momentous deeds.”

22

The fighting began as the first rays of dawn revealed the countryside. At first there was sporadic firing, which grew louder and heavier as pockets of engagement blossomed into fields of thunder and flying debris.

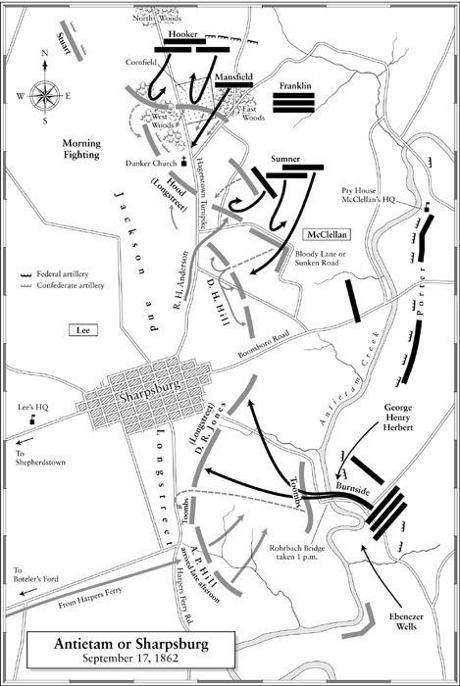

Map.11

Antietam or Sharpsburg, September 17, 1862

Click

here

to view a larger image.

As in previous battles, the landscape imposed itself on the fighting. “At Antietam it was a low, rocky ledge, prefaced by a corn-field,” wrote a Union soldier. “There were woods, too, and knolls, and there other corn-fields; but the student of that battle knows one cornfield only

—the

corn-field … about it and across it, to and fro, the waves of battle swung almost from the first.” By 10:00

A.M.

the Confederates were in possession of the field that, instead of corn, contained the bodies of more than a thousand dead and wounded men.

23

When the fighting shifted to the woods, Federal troops discovered to their horror that a battery of Confederate artillery had been swiftly moved to block the retreat. John Pelham, the twenty-four-year-old captain in charge of the artillery, was already something of a hero in the South. During Antietam, his unflinching precision under fire made him a legend. After the battle, Stonewall Jackson said of him, “Every army should have a Pelham on each flank.” Henry MacIver happened to be delivering a message to Pelham when Federal cavalry attacked the position. The charge was so swift that Pelham and his men had only enough time to draw their revolvers. But the Scotsman never had a chance to use his: a bullet smashed through MacIver’s mouth, taking four teeth and part of his tongue with it before exiting through the back of his neck.

24