A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (56 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Lincoln’s cabinet was grim when it learned that a Confederate army was marching unopposed toward Kentucky. As Lincoln’s frustration with Buell increased, he turned to General Pope to stop the run of bad news. Pope, at least, claimed to be thirsting for battle. The self-promoting victor of Island No. 10 had recently boasted to the press that his soldiers only ever saw the backs of the enemy. Pope liked to make “hard war.” Unlike McClellan, he was less concerned about keeping casualty figures to a minimum, nor did he believe in protecting civilians from the ravages of war. He wanted Southerners to suffer, because he thought it would make them more willing to surrender. But in one important sense, Pope was just the same as McClellan: he underestimated his opponent.

The Seven Days’ Battles had brought out the fighter in Lee. The once cautious officer had undergone a metamorphosis into a resolute and audacious general. He had private reasons, too, for wanting to throw the Federals out of Virginia. At the start of the war he had lost the family home of Arlington, across the river from Washington. Shortly after the Seven Days’ Battles, his other home, the White House plantation in central Virginia, was burned to the ground by Federal soldiers, forcing his wheelchair-bound wife, Mary, to seek refuge in Richmond.

77

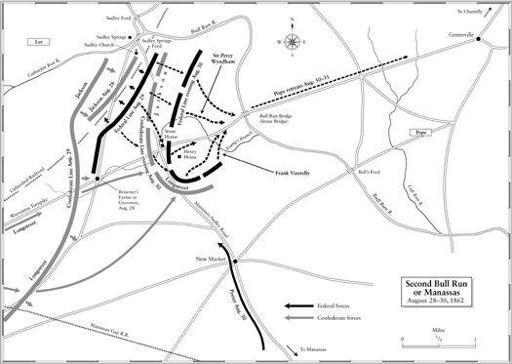

Lee divided his army of fifty thousand into two “wings” so that he could attack Pope from several directions, a risky tactic given his inferior numbers. Stonewall Jackson was given command of one, and General James “Old Pete” Longstreet, who had performed well during the Seven Days’ Battles, the other. Jackson’s division struck first, tearing into Pope on August 9. He launched another surprise attack against Pope two weeks later, and followed it up on the twenty-seventh with a raid on Pope’s supply depot at Manassas Junction. “Huzza,” crowed John Jones, the usually cynical clerk at the Confederate War Department. “The braggart is near his end.”

78

Jackson’s raid gave away his position; Pope ordered his commanders to prepare the men for battle. The name Manassas conjured up dreadful memories for the North. “Everything is ripe for a terrible panic,” Charles Francis Adams, Jr., wrote to his father from Washington. “I have not since the war began felt such a tug on my nerves.”

79

Pope had superior numbers to Jackson but not by an overwhelming margin. McClellan had played into Lee’s hands; mortified by his demotion, he had resisted for as long as possible Halleck’s orders to reinforce Pope. He knew that a battle was fast approaching and wanted to watch his rival “get out of his scrape by himself.” Among the reinforcements who did reach Pope, however, was Sir Percy Wyndham, who had been exchanged and was able to rejoin his regiment just in time to participate in the “scrape.”

12.5

The Second Battle of Bull Run began piecemeal on August 28 and roared into life on the twenty-ninth. In the thirteen months since the first battle, the armies had grown in size and the men had become hardened and more experienced. Once again, Henry House Hill became the focus of bitter fighting, although this time it was the Federals who held the hill and the Confederates who were cut down trying to dislodge them. Pope had no idea that Lee and Longstreet had arrived with the other half of the Army of Northern Virginia. After the firing drew to a halt on the evening of the twenty-ninth, Pope was so confident he had won that he sent a dispatch to Washington announcing his victory. He was unprepared for the full Confederate assault the following day. At 7:00

P.M.

on the thirtieth, a shocked and disconsolate Pope reluctantly ordered his army to retreat.

Map.10

Second Bull Run or Manassas, August 28–30, 1862

Click

here

to view a larger image.

Ill.22

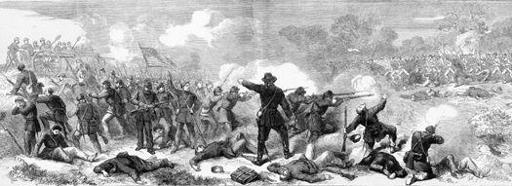

The Federal army makes its stand on Henry House Hill, Second Bull Run, by Frank Vizetelly.

The 1st New Jersey Cavalry was massed behind a thickly wooded forest with orders to stop the retreat from turning into a rout, but as tens of soldiers became hundreds and then thousands, the regiment lost its cohesion. Stray gunfire contributed to the Cavaliers’ difficulties. Above the din came the order to fall back, which some of the riders interpreted to mean they could gallop off, touching a nerve with Sir Percy. The familiar twiddling of his mustache began. Threatening to shoot any man who disobeyed, he forced the men to bring their horses back into line and perform the action as though they were on parade. “The twirl of that long moustache,” wrote the regiment’s chaplain, “was more formidable than a rifle.”

80

There were five thousand casualties at the first Battle of Bull Run; at the second, twenty-five thousand. Lee had lost proportionately more men, however, and his army was in no shape to pursue the Federals.

12.6

Lincoln had eaten dinner at Secretary Stanton’s house on the thirtieth, thinking that Pope was his man. But by the time he retired to bed, the news had come through of the army’s defeat. Once again, the residents of Washington woke up to the sight of leaderless soldiers pouring through the streets, filthy, hungry, and clearly in search of a drink. Only this time, behind them came wagon after wagon of the wounded and dying. “So,” lamented the treasurer of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, George Templeton Strong, “after all this waste of life and money and material, we are at best where we were a year ago.”

82

12.1

In the same letter, Spence also suggested that the Southerners consider changing their name from Confederate States to “Southern Union,” which sounded better to English ears. When Mason forwarded his request to Benjamin, he asked the secretary of state not to take offense. Spence’s objection to the word “Confederacy” sounded lunatic, Mason admitted, but he was speaking “from an English business point of view.” He assured Benjamin that on all other matters Spence was a “man of large research, liberal and expanded views.” Moreover, he had close ties to

The Times,

and his book,

The American Union,

continued to outsell every other work on the subject.

25

12.2

Le Constitutionnel

was generally considered to be the mouthpiece of the French government. This “seems like a preparation of the public mind for a mediation on the part of France in the American conflict,” noted the diarist Henry Greville on June 2, “and to-day

The Times

has put forth a leader strongly advocating it.”

38

12.3

Although the strike leaders Aitken and Grimshaw were able to call out large meetings all over Lancashire, achieving an unambiguous vote in favor of Southern independence was proving to be a considerable struggle. A meeting in Ashton, which was one of the most deprived towns in the area, ended with a resolution in favor of recognition for the Confederacy, but someone from the floor successfully tacked on an amendment that urged Britain and France to “crush the abettors of slavery and oppression.”

41

12.4

Although General Winfield Scott’s “Anaconda Plan” to isolate and squeeze the South was never formally adopted, this effectively became the strategy of the war.

12.5

The North and South copied the European system of parole and exchange of prisoners. Prisoners gave their word—their parole—not to take up arms until they were formally exchanged for an enemy prisoner of equal rank. If the wait for exchange was going to take more than a few days, parolees could go home or to a parole camp and wait until they received notice that the paperwork had been completed.

12.6

Among the Confederate prisoners was the accident-prone Garibaldi veteran Lieutenant Henry Ronald MacIver, who had received a bullet in the wrist. An Irish Federal surgeon bandaged his arm with more skill than he could have hoped for, and afterward MacIver was transferred to Alexandria. He was, wrote his biographer, “somewhat dismayed to find himself face to face with his old jailer … he saw that the man recognised him as his former prisoner the instant they met.”

81

THIRTEEN

Is Blood Thicker Than Water?

The possibility of intervention—Lee invades the North—Antietam, the bloodiest day—Dawson experiences Northern hospitality—The splendors and shortages of Richmond—Meeting the Confederate generals

“T

he suspense was hideous and unendurable,” Henry Adams recalled, as he waited for news from America.

1

On September 9, 1862, came a telegram from Reuter’s agency announcing a victory for Union general John Pope at Bull Run. “This has been a Red Letter Day,” Moran wrote euphorically. “If this be true it is the beginning of the end.”

2

Four days later, Moran learned they had been misled; Pope had been defeated, and the Confederate army was just twenty miles from Washington. “My heart sunk within me,” he wrote. “The rebels here are elated beyond measure. The Northern people are looked upon as cravens, and the Union is regarded as hopelessly gone.” He was alone at the legation; the Adamses were away and Charles Wilson had taken a leave of absence “for his health.” With no one to act as a moderating influence on his behavior, Moran happily insulted a British Army officer who called at the legation to volunteer for the Federal army; “they think we are unable to attend to our affairs, and that they can settle them,” he remarked testily.

3

The Adams family said goodbye to their hosts and returned to London as soon as they heard the news. Mrs. Adams told Moran that it would have been “torture” to remain, since there were Confederate sympathizers among the house party. Henry suffered pangs of guilt that so many were risking their lives while he was fighting the battle of the drawing rooms. “After a sleepless night,” Henry subsequently wrote of his younger self, “walking up and down his room without reflecting that his father was beneath him, he announced at breakfast his intention to go home into the army.”

4

Lord Russell had been wavering over whether Britain should intercede, until he received the reports about the Second Battle of Bull Run.

5

Charles Francis Adams had come away from their meeting on September 4 thinking it was business as usual, since Russell had assured him “I [could be] quite at ease in regard to any idea of joint action of the European powers in our affairs. I laughed and said I was in hopes that they all had quite too much to occupy their minds … to think of troubling themselves with matters on the other side of the Atlantic.”

6

But a day later, the Confederate commissioner in Brussels, Ambrose Dudley Mann, reported that he had just received a letter from his informant in London, “an influential Englishman,” who wrote that there was “a steady progress of opinion in one direction” regarding Palmerston and Russell. As to the latter, “I am informed upon the most credible authority, [Russell is] perfectly satisfied that there is not so much a shadow of a chance for the Yankees to overpower the united and resolute South, and that he would not be opposed to intervention if a reasonable hope could be entertained of its acceptance by the administration at Washington.”

7