A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (40 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Emotions were running high in the Senate. A last-ditch attempt by Senator Hale to force a resolution against releasing the rebel commissioners prevented Sumner from attending the meeting on the twenty-sixth. His absence allowed Seward to explain his letter to a far less critical audience. Seward kept expecting Lincoln to offer his alternative, but the president said nothing, and after comparatively little discussion, the cabinet approved Seward’s proposal. He could hardly believe the sudden change of opinion. When the others had filed out, Seward turned to Lincoln and asked him why he had not made the case for arbitration. Because “I could not make an argument that would satisfy my own mind,” the president replied.

73

The cabinet had agreed to say nothing of the matter until Lyons received Seward’s letter on the following morning, the twenty-seventh. That night, Sumner was in an ebullient mood when he attended a dinner given by William Howard Russell. After some diversionary talk about Prince Albert’s death, the discussion turned exclusively to the

Trent.

Even at this late stage, Russell told the group, he had not heard a single voice in favor of giving up the Southerners; the government would never be able to pull off something so unpopular. But Sumner corrected him. There was no need for the administration to do anything so drastic, he insisted. “At the very utmost,” he declared, “the Trent affair can only be a matter for mediation.” Russell assumed that he was hearing the official line, since Sumner was in “intimate rapport with the President.”

74

The next day Russell was reading the Washington newspapers, which were still insisting that the rebels would never be given up, when he received a note from one of the secretaries at the British legation. “What a collapse!” he wrote, a trifle disappointed that it was back to business as usual. Sumner’s surprise was even greater. Not twenty-four hours ago, the president had been adamantly opposed to any such settlement. Sumner had already accepted Seward’s invitation to dinner that night. Begging off now would only call attention to his defeat.

Among the guests at Seward’s was Anthony Trollope, who was oblivious to the drama unfolding in front of him.

75

Charles Sumner was unusually quiet and left the talking to Senator Crittenden, who made disparaging comments about Florence Nightingale to Trollope, no doubt unaware that the woman whose reputation he was trashing had recently donated her sanitation reports and hospital plans to the U.S. War Department.

76

Seward played the genial host to the hilt; after dinner, he invited the four senators at the table to accompany him to his study. He bade them all sit down while he took out the dispatches from London and Paris. To these he added his twenty-six-page reply to Lord Russell, his dispatch to Charles Francis Adams, and his response to the French foreign minister. Sumner and the others then had to sit in silence while Seward read out every line.

77

—

A week later, on January 1, 1862, the two Confederate commissioners and their secretaries sailed for England on board the warship HMS

Rinaldo.

“[The Americans] are horribly out of humour,” Lyons wrote to Lord Russell on December 31. He did not think this was the end of the story, but for now they could put their faith in Seward. “For he must do his best to maintain peace, or he will have made the sacrifice … in vain.”

78

Seward had triumphed, but only just, and only for the moment. His reply to Russell, which Seward had composed with his domestic audience firmly in mind, failed as a legal document or as a new elaboration of U.S. foreign policy, but it successfully appealed to Northern readers, especially the part where he claimed that because of the

Trent

case, Britain would never again attempt to impress American sailors (a practice last used in 1812).

Sumner tried to diminish Seward’s victory by claiming that the president had preferred arbitration but the need for a quick decision had forced him into a hasty act.

79

There was perhaps some consolation to him in the vitriolic and bitter speeches that enlivened Congress during the first week of January. On the ninth, Sumner gave a long speech in the Senate that was meant to explain and justify the government’s decision. All the press, most of the president’s cabinet, nearly every senator, and all the foreign ministers—except Lord Lyons—went to hear the performance. Senator Sumner had dressed for the occasion. Afterward, he was remembered as much for his olive-green gloves and tailored suit as for what he said. It was notoriously hard to follow Sumner. “He works his adjectives so hard,” a journalist once commented, “that if they ever catch him alone, they will murder him.”

80

He spoke for three and a half hours, flatly contradicting many of the arguments Seward had employed in his dispatch to Lord Russell.

The public’s response exceeded all Sumner’s expectations. There were tributes and editorials in the press. People who usually avoided him because of his abolition politics were eager to shake his hand.

81

Sumner’s previous criticisms of Seward’s reckless diplomacy were repeated and turned into the reason for Britain’s “overreaction.” The remarkable courage and patriotism Seward had displayed in forcing the cabinet to make an unpopular decision were brushed aside.

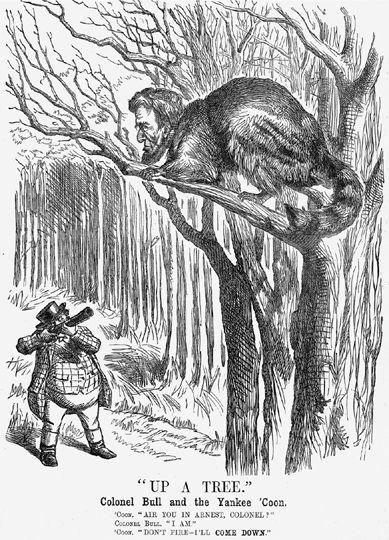

Ill.13

Punch crows after the Union backs down, January 1862.

Lord Lyons knew what it was like to have one’s intentions maligned and efforts discounted, and he was among the few people in Washington who secretly applauded Seward for his bravery. The shy minister did not know it, but he, too, had gained an admirer on account of his behavior during the crisis. As “one who witnessed the difficulties of Lord Lyons’s position here, and how his pathway was strewn with broken glass,” wrote Adam Gurowski, the State Department’s chief translator, “[I] must feel for him the highest and most sincere consideration.… During the whole

Trent

affair, Lord Lyons’s conduct was discreet, delicate, and generous … a mind soured by human meanness is soothingly impressioned by such true nobleness in a diplomat and an Englishman.”

82

8.1

It may have disappointed Northerners to know that the prisoners ate far better and had larger rooms than the regulars at Willard’s.

8.2

Gladstone was posturing for effect; Wilkes had clearly violated international law both by taking the Confederates off the ship and by acting as his own court of law in determining that they could be taken instead of going to a prize court, which alone had the authority to make such a ruling. The prize court would have set the

Trent

and the Confederates free, since people can’t be kidnapped willy-nilly off the high seas. Wilkes’s argument, that the Confederates were a living, breathing dispatch, which made them in legal terms “contraband of war,” would have been laughed out of court. But the likelihood is that Wilkes would have precipitated a crisis even if he had sailed to a prize court, because England would have demanded an apology from the United States for stopping a British mail ship without cause, and the apology would have become the sticking point.

8.3

Years later, Queen Victoria wrote of the memorandum: “This draft was the last the Beloved Prince ever wrote.”

NINE

The War Moves to England

Hard times in Lancashire—Burnside captures Roanoke—The sorrows of Lincoln—A victory at last—Mason and Slidell arrive in Europe—Dawson joins the

Nashville—Southern

propaganda—The debate in Parliament

“W

e are beginning the New Year under very poor prospects,” recorded a cotton spinner named John Ward from Clitheroe on January 1, 1862. Twenty-seven thousand workers in Lancashire had been fired and another 160,000 were, like him, surviving on short time. Families on his street were selling their furniture to buy food. “A war with America” would be the final straw, wrote Ward, “as we will get no cotton.… Every one is anxious for the arrival of the next mail, which is expected every day.”

1

In Liverpool, crowds gathered each morning on the quayside waiting for America’s response. The arrival of the

Africa

on January 2 caused brief excitement, but she carried only newspapers in her hold. The telegrapher Paul Julius de Reuter came to see Charles Francis Adams on Monday the sixth to ask if the minister would be so kind as to alert him the minute there was news. “He little imagines how entirely my government keeps me without information,” Adams wrote angrily.

2

Two days later, it was Reuter who did Adams the kindness; his office had received an early telegram announcing the commissioners’ release. Weed came an hour later to confirm that it was all over London. Adams’s relief was tempered by his vexation at being the last to know.

Benjamin Moran rushed to St. James’s, the club of the diplomatic corps on Charles Street and probably the only club in London that would have him. For once he was the center of attention as two dozen minor diplomats and secretaries “sprang to their feet as if electrified,” he wrote. Several even shook his hand before running off to the telegraph office. “In a few minutes messages were flashing over the wires to all the Courts of Europe.” In the West End theaters, evening performances were already under way, but as soon as the curtains fell on the first act the news was announced, causing audiences to rise spontaneously and cheer.

3

Within the British cabinet, however, reactions were rather more mixed: “The Admiralty is flat and dull, now there is to be no war,” the Duke of Somerset wrote sarcastically to his son, Lord Edward St. Maur.

4

Ill.14

Punch depicts the United States as a recalcitrant child in need of a whipping.

More than £2 million had been spent in the scramble to get ships and troops to America. It would be some time before soldiers came home. Jonny Stanley wrote to his parents from Montreal to say that he was safe although lonely. The infinite forests and frozen lakes of Canada were “very dull, and the people, however socially inclined, thoroughly different in manners and ways of thinking.”

5

The troops had so little to do that a sizable number would slip away over the winter months, only to reappear on the other side of the American border as Northern volunteers.

6

The press assumed that relations between the two countries would quickly return to normal. The

Illustrated London News

congratulated England for having dealt with the crisis so adroitly. “We are therefore clear of all blame in the whole transaction,” it opined on January 11, “and legally, morally, and even sentimentally, we have shown ourselves friends to the Americans.”

7

This was not the view of 20 million Americans. Huddled in his frozen headquarters in northern Virginia, Union general George Meade wrote to his wife that “if ever this domestic war of ours is settled, it will require but the slightest pretext to bring about a war with England.”

8

A congressman from Illinois swore on the floor of the House that he had “never shared in the traditional hostility of many of my countrymen against England. But I now here publicly avow and record my inextinguishable hatred of that Government. I mean to cherish it while I live and to bequeath it as a legacy to my children when I die.” From Paris, Seward’s unofficial emissary Archbishop Hughes exhorted him to remember that the “awful war between England and America must come sooner or later,—and in preparing for it, even now, there is not a moment to be lost.”

9