A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (36 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Charles Francis Adams was not at the legation to hear the news. He had accepted an invitation from Richard Monckton Milnes to join a large house party at Fryston Hall in Yorkshire. Neither Charles Francis nor Abigail had experienced life in a grand country house before; Fryston’s “somewhat ancient” decoration and total lack of modern conveniences confirmed their prejudices about the superiority of New England to Olde England. The wet weather forced the guests to huddle together in Milnes’s library, whose relatively efficient fireplace made it also double as the breakfast room. By the twenty-seventh, the guests had become restless. Unable to stand the confinement any longer, the group—which included the MP William Forster, the novelist Elizabeth Gaskell, and Austen Henry Layard, the excavator of the ancient city of Nineveh (who had recently put away his tools to become Lord Russell’s undersecretary for foreign affairs)—accepted Milnes’s invitation to brave the rain for a visit to the ruins of Pomfret Castle.

A messenger bearing Moran’s telegram from London tracked Adams down at the ruins. The minister would always remember standing in the persistent drizzle making polite conversation with his fellow guests while in his hand he clutched the news about the

Trent.

“We had a very dark and muddy walk home,” he recorded. William Forster accompanied him, but Adams did not reveal the contents of the telegram, Forster told his wife, until “as we got in, Adams said, in his cool, quiet way ‘I have got stirring news.’ ” Forster continued: “I think he is as much grieved as I am, and does not think a hundred Masons and Slidells would be worth the effect on us.” The news had spread by dinner, making it a torturous affair. No one knew what to say, and Forster’s attempts to make conversation were so ham-fisted that Adams could not help commenting in his diary: “He is no courtier.” In the end, it was left to a local manufacturer who had been invited to make up the numbers to fill the void, which he did at great length in a diatribe addressed solely to Adams on the iniquities of the Morrill Tariff.

60

The next morning, Layard and Forster went to London immediately after breakfast. Adams thought it best to travel by a different train and left at noon. Milnes and his wife were so warm and earnest at the parting that Adams felt rather emotional; it seemed at that moment as though no one in England had ever been so kind to him. He arrived at the legation in the evening to find Henry, Moran, and Wilson overexcited and once again making inappropriate comments to a crowd of visitors. A note from Lord Russell was waiting on Adams’s desk. The hour was late, he realized with a tinge of relief. The meeting would have to wait until tomorrow, giving him a little more time to prepare.

“There was a shade more of gravity visible in his manner, but no ill will,” Adams wrote after the interview on the twenty-ninth. He had decided to be frank with the foreign secretary. “Not a word had been whispered to me about such a project,” he confessed. This seemed to reassure Russell, who then asked whether the

Adger

had received orders respecting British vessels. Adams replied no, not as far as he knew. There was nothing more to be said by either man. “The conference lasted perhaps ten minutes,” Adams recorded. He could not imagine Seward being as civil in similar circumstances. But he was under no illusions that Lord Russell’s politeness signified an unwillingness to retaliate. During the carriage journey home, Adams wondered if this had been his final visit to the Foreign Office: “On the whole, I scarcely remember a day of greater strain in my life.”

61

The press, he saw, was urging the government to stand up for British rights. Even liberal papers like the

Manchester Guardian

accused the American government of testing “the truth of the adage that it takes two to make a quarrel.”

62

Lord Russell described his conversation with Adams at a hastily called cabinet meeting on Friday, November 29. Every member was present, except for the Duke of Argyll, who was on holiday in France. Palmerston was bristling with pugnacious indignation. He had spent the past few days calculating ship distances and totting up troop numbers. Whether Captain Wilkes’s act had been premeditated or not, Palmerston had decided it was time “to read a lesson to the United States which will not soon be forgotten.”

63

7.1

Lyons suspected that Seward and Mercier had only a vague idea of what the other was saying, and although he faithfully reported all that Mercier told him, Lyons warned Lord Russell not to take his words too literally. “Your Lordship will not fail to recollect that the conversation, which was carried on in English, was repeated to me by M. Mercier in French, and that it took place between a Frenchman not very familiar with English, and an American having little or no knowledge of French.”

18

7.2

Cambridge House, wrote Sir George Trevelyan memorably, was “Past the wall which screens the mansion, hallowed by a mighty shade, / Where the cards were cut and shuffled when the game of State was played.”

EIGHT

The Lion Roars Back

Captain Wilkes seizes the

Trent—

Northern glee—Britain prepares for war—Prince Albert’s intervention—Waiting for an answer—Seward’s dilemma—Lord Lyons takes a risk—Peace and goodwill on Christmas Day

“A

cold, raw day,” William Howard Russell noted in his diary on November 16, 1861. “As I was writing,” he continued, “a small friend of mine, who appears like a stormy petrel in moments of great storm, fluttered into my room, and having chirped out something about a ‘jolly row,’—‘Seizure of Mason and Slidell,’—‘British flag insulted,’ and the like, vanished.” Russell hastily grabbed his coat and followed him outside, where he bumped into the French minister, Henri Mercier, coming from the direction of the British legation. “And then, indeed, I learned there was no doubt about the fact that [on November 8] Captain Charles Wilkes, of the U.S. steamer

San Jacinto,

had forcibly boarded the

Trent,

a British mail steamer, off the Bahamas, and had taken Messrs. Mason, Slidell, [and their secretaries] Eustis, and Macfarland from on board by armed force, in defiance of the protests of the captain and naval officer in charge of the mails.”

1

The American press was jubilant over the capture. “Rightly or wrongly, the American people at large look upon it as a direct insult to the British flag,” wrote Lord Lyons.

2

But the opportunity to humiliate England was not the only reason behind the public’s excitement. Mason and Slidell had been needling the North from the Senate floor for many years, and their banishment to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor was deemed a fitting punishment.

8.1

The New York Times

’ first editorial on the affair called for Wilkes to be honored with a medal or a public holiday. The Philadelphia

Sunday Transcript

went further and committed the country to war, reminding its readers that American soldiers had routed “the best of British troops” in 1812 and would do so again. “In a word, while the British government has been playing the villain, we have been playing the fool,” the paper declared. “Let her now do something beyond driveling—let her fight. If she has a particle of pluck … if she is not as cowardly as she is treacherous—she will meet the American people on land and on the sea, as they long to meet her, once again, not only to lower the red banner of St. George … but to consolidate Canada with the union.”

3

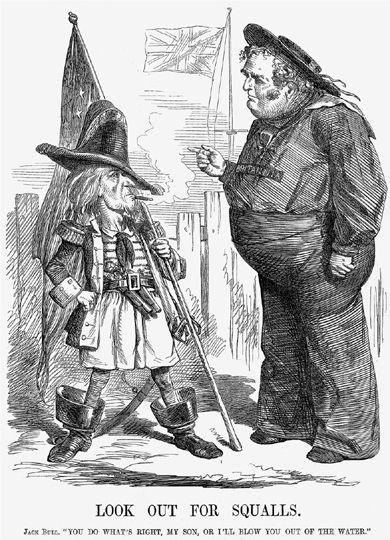

Ill.11

Punch sends a British warning to the United States, December 1861.

What was not clear to Russell, however, was whether Captain Wilkes had acted on his own or in accordance with secret U.S. government instructions. His visits to the State and Navy departments on November 18 were inconclusive, since the former was not prepared to comment, but the latter had obviously been taken by surprise.

4

No one at the Navy Department had a good word to say in Wilkes’s defense. Although a renowned cartographer, he had the reputation of being a bully and a braggart.

5

The command of the

San Jacinto

had been given to him with great reluctance; “he has a super-abundance of self-esteem and a deficiency of judgment,” warned an official in August. “He will give us trouble.”

6

Since his appointment, Wilkes had been trawling the oceans in defiance of his actual orders on a personal hunting expedition for Confederate ships. It was sheer luck that he stumbled onto the Confederate commissioners, and it was pure Wilkes—his colleagues told William Howard Russell—to decide that a search and seizure of the four men on a neutral ship would be legal under international law.

At the British legation, Russell encountered Lord Lyons politely fending off questions from a group of foreign ministers who had come ostensibly to offer their support, but really to ascertain England’s probable response. This, Lyons made clear, would have to come from London. He explained to Russell that his overriding concern was to prevent anything coming from himself or the legation that might help the warmongers. The staff had been given orders not to discuss the

Trent

with anyone, although Russell could see from the look on their faces that they thought war was inevitable.

The following day, Russell prepared his letter to

The Times.

“I rarely sat down to write under a sense of greater responsibility,” he admitted in his diary.

7

Russell assumed that his report would be “the first account of the seizure of the Southern Commissioners which will reach England,” and the thought of how the public would react to the news filled him with foreboding. He was no longer just describing the attack on the

Trent,

but also the North’s exultation and the U.S. government’s silence, which he feared would be as provocative to the English as Wilkes’s original act. Without excusing the Lincoln administration, Russell tried to explain the pressures placed upon it by democracy: “There is a popular passion and vengeance to be gratified by the capturing and punishment of Mr. Mason and Mr. Slidell,” he wrote, “and I believe the Government will retain them at all risk because it dare not give them up.”

8

Russell was only partially correct about the administration. Public opinion naturally played a role in its deliberations, but from the start virtually all the members of the president’s cabinet were adamantly opposed to releasing the commissioners. Lincoln allegedly complained to a journalist on November 16 about the embarrassment Wilkes had caused the country. “I fear the traitors will prove to be white elephants,” he reportedly said. “We must stick to American principles concerning the rights of neutrals. We fought Great Britain for insisting, by theory and practice, on the right to do precisely what Captain Wilkes has done.”

9

If that is true, Lincoln would have been the only member of his administration, apart from Montgomery Blair, the postmaster general, to accept that Wilkes had violated international law and the only member to realize the grave threat to America’s moral reputation if the government supported him. The United States had fought the War of 1812 in part to defend its broad interpretation of “neutral rights.” It had protected the slave trade, allowing it to flourish, and had expelled the British minister, John Crampton, in 1856, risking a third Anglo-American war, for his perceived violation of these rights. The United States would be inviting the censure and mockery of the entire world if the government suddenly repudiated a fundamental principle of American foreign policy because it was no longer expedient to maintain.

Regardless of how Lincoln originally understood the issue, within twenty-four hours of hearing the news he had joined the celebrations. He wrote about the seizure with exclamation marks to Edward Everett, the former American minister in London. To General McClellan, who came to deliver a warning from the Prince de Joinville that England would demand an apology, Lincoln replied categorically that the commissioners were not going to be released. The cabinet, excepting Montgomery Blair, behaved shamefully. The worst offender was the attorney general, Edward Bates, who gave ill-judged and incorrect legal advice to his colleagues. “Some timid persons are alarmed, lest Great Britain should take offense at the violation of her Flag,” he wrote in his diary. “There is no danger on that score. The law of Nations is clear upon the point, and I have no doubt that, with a little time for examination, I could find it so settled by English authorities.”

10