A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (41 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Charles Francis Adams had neither the clarity of anger nor the cushion of complacency to comfort him. The news about the

Trent

had been followed by a letter from Charles Francis Jr. informing his family that he had joined the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry. The unexpected blow made ordinary business seem “utterly without interest,” wrote Adams.

10

The upset to the family was not enough, however, to divert attention from an embarrassing gaffe by Henry Adams. On January 10

The Times

revealed that “Mr. H. Adams,” the younger son and private secretary of the American minister, had published a mildly insulting article about English society for the American press. Henry had never intended to acknowledge “A Visit to Manchester” as his own, and so he had vented some of his frustrations about his social isolation in London society, pointedly remarking, “in Manchester, I am told, it is still the fashion for the hosts to see that the guests enjoy themselves. In London the guests shift for themselves … one is regaled with thimbles full of ice-cream and hard seed cakes.” Charles Francis Jr. had accidentally left Henry’s name on the manuscript when he sent it to the editor of the

Boston Courier.

11

Until then, Henry had been enjoying great success as the

New York Times

’ anonymous London correspondent. “The Chief,” as Henry called his father, gave his son a sharp dressing-down, so sharp that Henry briefly considered self-exile on the Continent.

12

He was teased without mercy by Benjamin Moran, who repeated ad nauseam “it is not every boy of 25 who can in 6 mos. residence here extort a leader from

The Times.

”

13

When he visited the Foreign Office on January 11 for his first meeting since the

Trent

crisis, Adams hoped that Lord Russell had not seen the

Times

article about his son. There was no cause for concern: Russell could be curiously obtuse about what he read in the papers. (Lady Russell had a far better understanding of the power of the press than her husband; she thought the American public had been goaded beyond endurance by the “sneering, exulting tone” in English newspapers after Bull Run.)

14

The two men passed the first half of the interview congratulating each other on preserving the peace, after which it was down to business again. Russell’s current concern was the risk to peace posed by Union and Confederate cruisers. The

Sumter

had recently arrived at Cadiz, having destroyed a number of U.S. merchant ships along the way. The government expected a confrontation with a U.S. Navy ship but would not tolerate a free-for-all in British waters, which in Palmerston’s words would be a “scandal and inconvenience.” In Southampton, the disruption to ordinary business had risen to unsupportable levels; the crews of the CSS

Nashville

and USS

Tuscarora

—which had been pursuing the

Nashville

since December—were fighting each other in the streets.

15

Adams was caught by surprise, not having given a thought to either vessel during the past few weeks. It was back to the old state of affairs, he realized.

Life for all the occupants of the American legation was slowly returning to normal. People had stopped inviting them, Henry told Charles Francis Jr., “on the just supposition that we wouldn’t care to go into society.” The drought ended with a dinner at the Argylls’ on January 17. The evening passed far more enjoyably than the U.S. minister expected; Gladstone sat next to him and showed genuine interest in his views, and the guest on his other side praised him for “my conduct during the difficulties.” But Adams’s enjoyment was curtailed when the conversation turned to Seward and his now infamous quip to the Duke of Newcastle. “I feel my solitude in London much more than I do at home,” Adams wrote in his diary a short time later. “The people are singularly repulsive. With a very considerable number of acquaintances, I know not a single one whose society I should miss one moment.”

16

—

Adams did not know the true state of affairs in Washington, and Seward did not wish to enlighten him. The

Trent

was only one of many crises that threatened the administration during the winter of 1862. Criticism of the Federal government’s lack of progress was growing ever louder, with Lincoln receiving the largest share of the blame. The border states had not been secured, and the vast Army of the Potomac encamped around Washington had yet to do anything other than drill. Its leader, General McClellan, remained bedridden with typhoid. The War Department was riddled with incompetence and corruption and the Treasury had run out of gold, leaving Secretary Chase with no alternative but to print more money. On the night of January 10, Seward received a summons to the White House. There he found Chase, Assistant Secretary of War Peter Watson, and two generals gathered in a solemn huddle around the president. They had to act now, Lincoln told them, and find a way to produce victories or face the possibility “of our being two nations.”

17

Frustrated by the generals’ objections, Lincoln decided he would issue a presidential order for all naval and military forces to begin an advance on February 22, regardless of obstacles or delays.

The president’s frustration presented an opportunity for Seward to strengthen their relationship at a time when his own allies were deserting him in droves. “There is a formidable clique organized against Mr. Seward,” the attorney general noted in his diary on February 2. “I do not think I heard a good word spoken of Mr. Seward as a Minister even by one of his own party,” observed Trollope of his time in Washington. “He seemed to have no friend, no one who trusted him.”

18

Frank Blair, the powerful congressman from Missouri, complained to colleagues that Seward was “selfish, ambitious and incompetent” and apparently more concerned with fighting England than the South.

19

A senator attacked Seward for being “a low, vulgar, vain demagogue.”

20

Seward gave loyal service to Lincoln; while Mary Lincoln seemed incapable of fulfilling the role of confidante, the former contender for the White House found that he could adapt to the role with ease. Seward could not solve the president’s military problems, but he was able to smooth the way for the secretary of war’s departure on January 14, 1862, and the appointment of Edwin Stanton. The new secretary was arrogant and devious but, in contrast to Cameron, was efficient and would attack the department’s problems with energy. The amiable but useless Cameron chose to spend his forced retirement in Russia, where he replaced the equally useless Cassius Clay as minister.

Simultaneously with Cameron’s removal, some flicker of life appeared in the North’s military machine. On January 14, the English volunteer George Henry Herbert learned that the “Zou-Zous”—as members of the 9th New York Infantry (Hawkins’s Zouaves) were affectionately called—were going to evacuate from Hatteras Inlet. Despite the monotony of drilling and digging at Camp Wool, Herbert had never felt so content with his life. “Since I wrote to you I have received my promotion. I am now 2nd Lieutenant,” he informed his mother. He promised to send a photograph of himself in his new officer’s uniform in his next letter in case it was his last. “Our boys here are in high glee, we are going to leave Hatteras in a day or two,” he explained. “We are part of an expedition under the command of General Burnside. It consists of somewhere about an hundred vessels of all sorts, containing a land force of as near as I can learn, about 10,000 men of all arms. Its destination is unknown. The rumour is New Orleans. I fervently hope so.”

21

The rumors were unfounded. Thirteen thousand men were leaving Cape Hatteras, heading up the North Carolina sounds to the mysterious Roanoke Island, a forlorn stretch of grass and swamp between the mainland and the Outer Banks. Its first inhabitants, Sir Walter Raleigh’s ill-fated colonists, had survived in the New World for less than four years before they mysteriously disappeared. Three hundred years later the island seemed as untamed as ever. Its chief importance was strategic: whoever owned Roanoke held the key to Richmond’s back door.

22

General Ambrose Burnside (whose name and prodigious whiskers inspired the word “sideburns”) had convinced General McClellan that he could lead a combined amphibious force in light-draft and flat-bottomed boats that would have no trouble navigating the shallow waters of Roanoke Sound. The Confederate garrison guarding Roanoke was small and unlikely to withstand a sustained assault. Burnside was so confident that he gave permission for journalists to accompany the expedition. William Howard Russell heard the news from his sickbed in a hotel in New York. The journalist had been worn down by the unrelenting campaign of abuse against him: “There is a sort of weakness and languor over me that I never experienced before,” he told Delane. Frank Vizetelly would go and report for both of them.

23

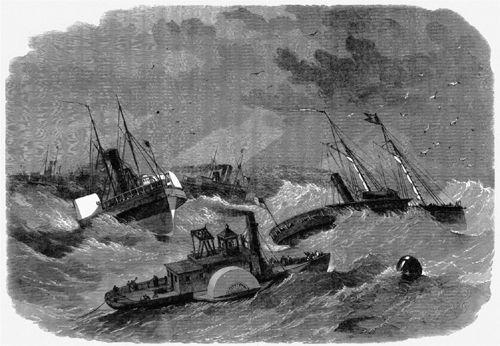

Ill.15

USS Picket leading the ships of the Burnside expedition over the Hatteras Bar in North Carolina, by Frank Vizetelly.

Vizetelly, so deep in debt that even Russell would no longer lend him money, was overjoyed at the prospect of escaping Washington. He joined Burnside’s flotilla on January 10 with nothing else except a small bag containing a change of clothes and his pencils. “Woe is me!” he wrote after several days of crashing seas and hurricane winds. One night, a thunderous wave hit the boat with such force that he was catapulted from his bed against the cabin door, which burst open, depositing him with a thud in eight inches of briny water. He decided this would be his first and last amphibious expedition.

24

The first phase of the attack was easily accomplished and the southern half of Roanoke Island was captured on February 7 without Herbert or his friends firing a shot. “Day broke cold, damp, and miserable,” Vizetelly wrote on the eighth. “After a drink of water and a biscuit for each man, the Federal force prepared to advance into the interior.”

25

Cannon fire alerted Herbert that it would soon be his regiment’s turn to leave the makeshift camp. “Near the centre of the island it is very narrow and at the narrowest point a battery was erected,” he explained to his mother. “The road is in fact nothing but a cow path through fine woods and a thick growth of underbrush.”

26

The men had to march along the track two by two in order to allow room for the stretcher bearers carrying the wounded back to the ships. “I remember after that,” commented a private in the regiment, “a sort of sickening sensation as if I was going to a slaughter-house to be butchered.”

27

“At last we came in front of the battery,” wrote Herbert. The order came to charge and they plunged into the knee-deep swamp that surrounded the Confederate position. Vizetelly watched as they hurled themselves up the slope of the battery. The men behaved, he continued, “in the most brilliant manner, dashing through the swamp and over the stumps of the pine-clearing, and into the battery, which the Confederates were hastily leaving.” When they reached the top, they discovered that the rebels had fled. The 9th took up the chase for four miles and finally cornered the defenders at the northern tip of the island, in their own camp.

Herbert was delighted to hear that a journalist from the

Illustrated London News

was with them, and he asked his mother to look out for his reports. A total of 264 Union solders and 143 Confederates had been killed in the attack; later, he would consider such casualty numbers remarkably small, but for now he thought he had survived a great battle. Vizetelly admitted to being impressed. “I will not attempt to prophesy a triumph for the Federalists,” he told readers at home, “but, seeing the improved condition in the morale of the Union forces, and feeling somewhat competent to give an opinion, I am inclined to believe that these first successes are not to be their last. I have watched the Northern army almost from its first appearance in the field. I have seen it a stripling … I now see it arrived at man’s estate.”

28

News of Burnside’s success on Roanoke Island reached Washington while the city was still under the rosy glow of Mary Lincoln’s triumphant White House ball held on February 5. The capital celebrated even harder when it learned that a great victory had been won in Tennessee. General Ulysses S. Grant had captured Fort Henry on the sixth and Fort Donelson on the fifteenth, giving him control of Tennessee’s two main rivers, the Cumberland and the Tennessee. An important water highway had been opened for the North, which ran from the north of Kentucky all the way down to Mississippi and Alabama.