Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk (17 page)

Read Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk Online

Authors: Peter L. Bernstein

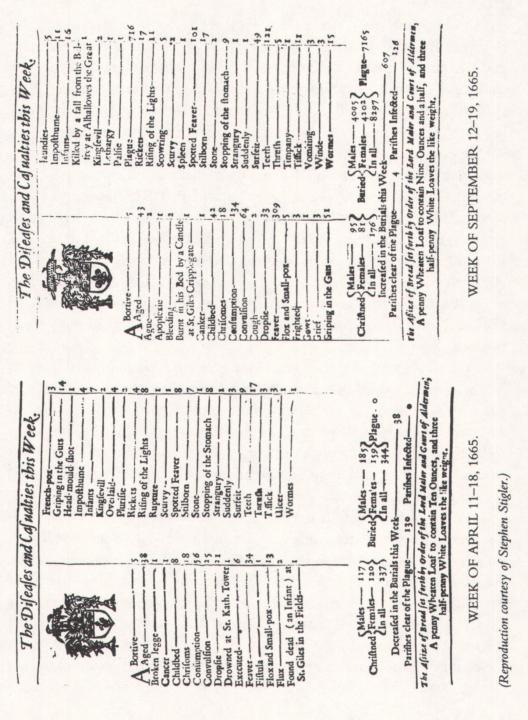

Graunt was particularly interested in the causes of death, especially "that extraordinary and grand Casualty" the plague, and in the way people lived under the constant threat of devastating epidemic. For the year 1632, for example, he listed nearly sixty different causes of death, with 628 deaths coming under the heading of "aged." The others range from "affrighted" and "bit with mad dog" (one each) to "worms," "quinsie," and "starved at nurse." There were only seven "murthers" in

1632 and just 15 suicides.

In observing that "but few are Murthered ... whereas in Paris few nights came without their Tragedie," Graunt credits the government and the citizen guard of the City of London. He also credits "the natural, and customary, abhorrence of that inhumane Crime, and all Bloodshed by most Englishmen," remarking that even "Usurpers" during English revolutions executed only a few of their countrymen.

Graunt gives the number of deaths from plague for certain years; one of the worst was in 1603, when 82% of the burials were of plague victims. From 1604 to 1624, he calculated that 229,250 people had died of all diseases and "casualties," about a third of which were from children's diseases. Figuring that children accounted for half the deaths from other diseases, he concluded that "about thirty six per centum of all quick conceptions died before six years old." Fewer than 4,000 died of "outward Griefs, as of Cancers, Fistulaes, Sores, Ulcers, broken and bruised Limbs, Impostumes, King's evil, Loprosie, Scald-head, Swinepox, Wens, &c."

Graunt suggests that the prevalence of acute and epidemical diseases might give "a measure of the state, and disposition of this Climate, and Air ... as well as its food." He goes on to observe that few are starved, and that the beggars, "swarming up and down upon this City ... seem to be most of them healthy and strong." He recommends that the state "keep" them and that they be taught to work "each according to his condition and capacity."

After commenting on the incidence of accidents-most of which he asserts are occupation-related-Graunt refers to "one Casualty in our Bills, of which though there be daily talk, [but] little effect." This casualty is the French-Pox-a kind of syphilis-"gotten for the most part, not so much by the intemperate use of Venery (which rather causes the Gowt) as of many common Women."`

Graunt wonders why the records show that so few died of it, as "a great part of men have, at one time or another, had some species of this disease." He concludes that most of the deaths from ulcers and sores were in fact caused by venereal disease, the recorded diagnoses serving as euphemisms.

According to Graunt, a person had to be pretty far gone before the

authorities acknowledged the true cause of death: "onely hated persons,

and such, whose very Noses were eaten of, were reported ... to have

died of this too frequent Maladie."

Although the bills of mortality provided a rich body of facts, Graunt

was well aware of the shortcomings in the data he was working with.

Medical diagnosis was uncertain: "For the wisest person in the parish

would be able to find out very few distempers from a bare inspection

of the dead body," Graunt warned. Moreover, only Church of England

christenings were tabulated, which meant that Dissenters and Catholics

were excluded.

Graunt's accomplishment was truly impressive. As he put it himself,

having found "some Truths, and not commonly believed Opinions, to

arise from my Meditations upon these neglected Papers, I proceeded further, to consider what benefit the knowledge of the same would bring

to the world." His analysis included a record of the varying incidence of

different diseases from year to year, movements of population in and out

of London "in times of fever," and the ratio of males to females.

Among his more ambitious efforts, Graunt made the first reasoned

estimate of the population of London and pointed out the importance

of demographic data for determining whether London's population was

rising or falling and whether it "be grown big enough, or too big." He

also recognized that an estimate of the total population would help to

reveal the likelihood that any individual might succumb to the plague.

And he tried several estimating methods in order to check on the reliability of his results.

One of his methods began with the assumption that the number of

fertile women was double the number of births, as "such women ...

have scarce more than one child in two years."12 On average, yearly burials were running about 13,000-about the same as the annual nonplague deaths each year. Noting that births were usually fewer in number

than burials, he arbitrarily picked 12,000 as the average number of births,

which in turn indicated that there were 24,000 "teeming women." He

estimated "family" members, including servants and lodgers, at eight per household, and he estimated that the total number of households was

about twice the number of households containing a woman of childbearing age. Thus, eight members of 48,000 families yielded an estimated 384,000 people for the total population of London. This figure

may be too low, but it was probably closer to the mark than the common

assumption at the time that two million people were living in London.

Another of Graunt's methods began with an examination of a 1658

map of London and a guess that 54 families lived in each 100 square

yards-about 200 persons per acre. That assumption produced an estimate of 11,880 families living within London's walls. The bills of mortality showed that 3,200 of the 13,000 deaths occurred within the walls,

a ratio of 1:4. Four times 11,880 produces an estimate of 47,520 families. Might Graunt have been figuring backwards from the estimate

produced by his first method? We will never know.

Graunt does not use the word "probability" at any point, but he was

apparently well aware of the concept. By coincidence, he echoed the

comment in the Port-Royal Logic about abnormal fears of thunderstorms:

Whereas many persons live in great fear and apprehension of some of

the more formidable and notorious diseases, I shall set down how

many died of each: that the respective numbers, being compared with

the total 229,520 [the mortality over twenty years], those persons

may the better understand the hazard they are in.

Elsewhere he comments, "Considering that it is esteemed an even

lay, whether any man lives ten years longer, I supposed it was the same,

that one of any ten might die within one year."t3 No one had ever proposed this problem in this fashion, as a case in probability. Having

promised "succinct paragraphs, without any long series of multiloquious

deductions," Graunt does not elaborate on his reasoning. But his purpose here was strikingly original. He was attempting to estimate average

expected ages at death, data that the bills of mortality did not provide.

Using his assessment that "about thirty six per centum of all quick

conceptions died before six years old" and a guess that most people die

before 75, Graunt created a table showing the number of survivors from ages 6 to 76 out of a group of 100; for purposes of comparison,

the right-hand column of the accompanying table shows the data for

the United States as of 1993 for the same age levels.

No one is quite sure how Graunt concocted his table, but his estimates circulated widely and ultimately turned out to be good guesses.

They provided an inspiration for Petty's insistence that the government

set up a central statistical office.

Petty himself took a shot at estimating average life expectancy at

birth, though complaining that "I have had only a common knife and

a clout, instead of the many more helps which such a work requires." 14

Using the word "likelihood" without any apparent need to explain

what he was talking about, Petty based his estimate on the information

for a single parish in Ireland. In 1674, he reported to the Royal Society

that life expectancy at birth was 18; Graunt's estimate had been 16.15

The facts Graunt assembled changed people's perceptions of what

the country they lived in was really like. In the process, he set forth the

agenda for research into the country's social problems and what could

be done to make things better.

Graunt's pioneering work suggested the key theoretical concepts

that are needed for making decisions under conditions of uncertainty.

Sampling, averages, and notions of what is normal make up the struc ture that would in time house the science of statistical analysis, putting

information into the service of decision-making and influencing the

degrees of belief we hold about the probabilities of future events.

Some thirty years after the publication of Graunt's Natural and

Political Observations, another work appeared that was similar to Graunt's

but even more important to the history of risk management. The

author of this work, Edmund Halley, was a scientist of high repute who

was familiar with Graunt's work and was able to carry his analysis further. Without Graunt's first effort, however, the idea of such a study

might never have occurred to Halley.

Although Halley was English, the data he used came from the

Silesian town of Breslau-Breslaw, as it was spelled in those dayslocated in the easternmost part of Germany; since the Second World

War the town has been part of Poland and is now known as Wrozlaw.

The town fathers of Breslaw had a long-standing practice of keeping a

meticulous record of annual births and deaths.