Alex's Wake (32 page)

Authors: Martin Goldsmith

We have traveled from the North Sea to the south sea, from sea to shining sea, in the space of one week. It took Alex and Helmut eighteen months to make the same journey. Our transportation has been an air-conditioned car cruising along superhighways and meandering through sometimes gentle, sometimes spectacular countryside. They made the journey on a bus and then by train at the point of a gun. We've lived off the fat of the land. By the time they reached Agde, they were lucky to receive two small meals a day. Tonight we will sleep on a comfortable mattress in a fine hotel with the waves of the Mediterranean murmuring in our ears as we drift off to a peaceful slumber. They spent their two months three miles inland, sleeping on unyielding wooden planks in a barracks that was made of reinforced cardboard and was open to the wind and winter weather, in a field surrounded by barbed wire.

I'm finding it very hard to stomach the contrast.

T

HERE HAS BEEN A SETTLEMENT

on this spot for more than twenty-five hundred years. The Greeks founded the city in the fifth century BC

and named it Agathe Tyche, or “Good Fortune.” Its fortune came largely from the waters; for centuries, Agde was one of the busiest fishing ports in the Mediterranean. The city's fish market is still dominated by a statue of Amphitrite, a sea goddess and the wife of Poseidon in Greek mythology. In the seventeenth century, Agde became the southern terminus of the Canal du Midi, an infrastructural wonder that connected the sea with the Atlantic Ocean one hundred fifty miles to the northwest, thus enabling travelers to save a month of travel time and to avoid the hostile Barbary pirates who lurked menacingly off the coast of Spain. Since 1697, Agde's coat of arms has featured three blue waves on a golden background, the waves representing the confluence of sea, ocean, and canal. During the last forty years, the neighboring town of Cap d'Agde has been transformed into one of the shimmering playgrounds of the Mediterranean, with many high-rise hotels on its shore and yachts moored in the safety of its slips.

As far as Alex and Helmut were concerned, the history of Agde began in early 1939, when the first of nearly five hundred thousand refugees from the Spanish Civil War began to stream across the French border. In February 1939, the French government gave the order to build six new camps to house those refugees, most of whom had fled over the cloud-topped passes of the Pyrenees in freezing weather and now found themselves homeless and penniless in a foreign land. The new camps, mostly in the southwestern regions of France, included facilities in Gurs, Le Vernet, Argelès-sur-Mer, Rivesaltes, and Agde, which received its first convoy of Spanish refugees on February 28.

Built to accommodate twenty thousand people, the Agde camp's population grew to more than twenty-four thousand by the middle of May. It was situated on what was then the outskirts of town, bordering the old Route Nationale 110, the Rue de Sète, now known as the D912. The conditions were primitive and the food scarce, but the refugees felt fortunate to no longer be in the line of Generalissimo Franco's fire. Among the inhabitants of the camp were Spanish artists who volunteered their services to paint colorful murals in the Agde City Hall and Spanish archaeologists who assisted in excavations that unearthed artifacts from the city's ancient Greek heritage.

In the summer of 1939, the French government offered the Spanish refugees three options for leaving the camp. They could join the French army and thus begin the process of becoming French citizens, they could return to Spain, or they could emigrate to Mexico. By late September, the refugees had made their choices and the Agde camp was nearly empty. But not for long. The previous year's infamous Munich Agreement had delivered a part of Czechoslovakiaâthe region referred to by Adolf Hitler as the Sudetenland, or South Germanyâto the expanding German empire. Tens of thousands of Czech citizens fled their homes. As part of its attempt to persuade the Czech government to accede to Hitler's demands, the French government offered temporary shelter to some of those refugees. In the autumn of 1939, about five thousand displaced Czechs moved into the same barracks in Agde that had recently housed the Spanish refugees. Then in May 1940, the Agde camp's population was increased by about fifteen hundred former citizens of Belgium who, like their Czech counterparts, had been displaced by the advancing German army. But after the signing of the armistice in June and with the assistance of the International Red Cross, the refugees slowly began returning home, and by late August the Agde camp was empty once more.

So when the Statute on Jews of October 3, 1940, went into effect, and zealots such as René Bousquet began their campaign to separate undesirables from mainstream French society, the camp at Agde was fully prepared to take in this new population. The first of the

Israélites étrangers

âforeign Jewsâarrived at the railroad siding in Agde in the last days of October. They were former citizens of Germany, Austria, Armenia, and Yugoslavia who had made their way to France thinking they had found a refuge from the Nazi plague that had infected their homelands. Alex and Helmut joined them on November 9, after having made the journey from Montauban in a boxcar designed for transporting cows and horses. I wonder if Alex, given his family's history with horses, ever gave thought to the tragic irony of this manner of transportation.

He and his son walked from the train station to the gates of the camp, carrying their meager luggage. Once they arrived, the travelers were divided into two groups: the women and children went in one

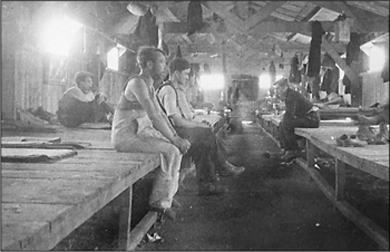

direction, while men and boys fourteen years of age and older were sent in another. Husbands and wives were kept apart. Alex and Helmut were assigned to Barracks No. 13 in Agde Camp No. 3, which was separated from the other camps and from the outside world by a fifteen-foot fence topped with barbed wire. The barracks were each about one hundred feet long, made of heavy cardboard to which had been added a layer of tar. The floors were slabs of concrete, the windows made of screens coated with plastic. On warm days, it was stifling inside the barracks; on cold days, it was bone-chilling.

A scene from the interior of one of the barracks of Camp d'Agde, showing the wooden benches that served as sleeping quarters. Conditions inside the barracks were either stifling or bone-chilling and there was nothing to do

.

(Services des Archives, Commune d'Agde)

When Alex and Helmut entered Barracks No. 13 on November 9, they were each handed a sack about three feet long and told to fill their sacks with straw from a pile in the corner of the barracks. The result was a makeshift mattress that would rest atop the wooden bench that would serve as their sleeping quarters. Their only privacy from other families was provided by a blanket hung from the low ceiling. Outside the barracks, there were a few taps that provided water for drinking

and washing, but no containers for transporting water into the barracks. Latrines were concrete structures with individual spaces for standing or squatting and large petrol drums below. The latrines naturally attracted vermin and clouds of flies.

Each camp had its own kitchen where meals were served twice a day, usually a thin soup with potatoes, occasionally supplemented with brown bread. One night in late November, when Alex and Helmut had been in Agde nearly three weeks, a fire broke out in the kitchen of the women's camp. Some of the men, realizing that a fire could easily consume the other tarred-cardboard barracks, attempted to cross into the women's camp to douse the flames, but they were beaten back by the camp's guards. The fire was extinguished before it spread, but soon thereafter the women's kitchen was replaced by a brick structure.

The guards of Camp Agde, the men (and a few women) who had prevented the prisoners from crossing into the women's camp, were all French. There were no Germans barking orders in their clipped, angular language; everything was spoken in the smooth vowels and throaty consonants of the Gallic vernacular. There were no beatings, no physical intimidation, no overt violence.

There was also nothing to do. The residents of Camp Agde aimlessly wandered the confines of their enclosures every day, “vegetating,” as one survivor described it. No one was killed; instead one rotted slowly.

After nearly a month of this existence, Alex characteristically decided to take matters into his own hands. He found some writing materials, sat down on his bench in his barracks, and wrote a letter, in literate and rather elegant French, to the prefect of Hérault in Montpellier. The letter, which I discovered in the holdings of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., is dated 5 December 1940 and displays the return address Camp 3, Barracks 13, Agde.

It is my honor to request your benevolence to help liberate myself and my son, Klaus Helmut, age 19, from the Camp in Agde.

On May 13, 1939, we boarded the steamship St. Louis, headed for Cuba, but due to a change in government we were unable to disembark in Havana, and we, along with a number

of the other passengers, had to disembark on June 20, 1939, in Boulogne-sur-Mer, where the French government kindly took us in.

A portion of Alex's letter to the prefect of Hérault, dated December 5, 1940. “It is my honor to request your benevolence to help liberate myself and my son . . . from the Camp in Agde.”

(Courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

During the winter of 1939â1940, my son and I became gravely ill. I myself was hospitalized in Contrexéville (Vosges) at the Central Hospital, where I remained for four months. My son suffered from chronic throat infections and, at one point, from pleurisy, and the doctor ordered an operation for him (attached please find the medical certificate). [Alas, the medical certificate disappeared sometime in the last seven decades.]

The American Joint Distribution Committee deposited $500 for each of us, thus a total of $1,000, so that we would not be a burden to the state. The Committee made this commitment to subsidize our needs until our departure oversees, which I hope is not far off.

I beseech you once again to grant our freedom, as the state of our health will not enable us to spend a winter in the camp.

In the hope that you will follow up my request, Monsieur le Prefet, I send my most respectful greetings.

Alex Goldschmidt

My grandfather's letter did not go unnoticed. Apparently, the prefect looked into the matter and asked a lower official, the

sous-préfet

of the town of Béziersâabout ten miles northwest of Agdeâto make some inquiries. On December 16, eleven days after Alex wrote his letter, the

sous-préfet

sent a note to the prefect of Hérault on paper bearing the words

Ãtat Français

, meaning “French state,” the name the Vichy government had adopted. The note read:

I have the honor to address herein the request made by Goldschmidt, Alex, who is currently interned at Camp Agde. He is soliciting the liberation of himself and his 19-year-old son Klaus.

The following information has been collected regarding the person concerned: German, resident of Martigny-les-Bains (Vosges) since July, 1939. No resources. Claimed by the

Comité d'Assistance aux Réfugiés

in Marseille (48 Rue de la Paix). The committee certifies that the American Joint Distribution Committee has made available to him and his family all the relief necessary to meet and sustain their needs.

Franz Kafka himself could not have written a more opaque, witless communiqué. Monsieur

sous-préfet

learns from the well-meaning people at CAR that the Joint has pledged some funds so that Alex and Helmut would not become, in Alex's words, “a burden to the state,” and concludes that all their needs are being met. The fact that Alex and his son have “no resources” is apparently trumped by the unseen but overwhelming benevolence of the Americans. Alex's request for liberation is mentioned but neither granted nor denied. Neither is the state of the two men's health a matter for consideration, despite the undeniable fact that winter weather has descended upon Agde and its weakened internees. A letter

has been received; the matter has been looked into; the bureaucracy's wheels grind on; there is nothing to be done.