Alex's Wake (35 page)

Authors: Martin Goldsmith

The food, such as there was, was bad. Meals always consisted of a thin soup made with potatoes, squash, turnips, parsnips, or cabbage. Occasionally, bread was served along with the soup, but never meat. There was also corn, but not the sort of sweet corn found growing stalk by stalk in the lush fields of Iowa or Illinois. This was feed corn, usually served by French farmers to their pigs; in Rivesaltes, it was fed to the Jews. In the spring of 1941, a representative of a Jewish relief agency visited Rivesaltes and reported that “while the normal daily ration

required by a human being lies between 2,000 and 2,400 caloriesâthe essential requirement being 1,500 caloriesâmost of the internees consume barely 800 calories.” The relief worker went on to point out that, due to the cold in the barracks and the often inadequate clothing worn by the unfortunates in the camp, many of those precious calories were lost every day to the exertion of shivering.

One latrine served every three or four barracks. Like the barracks, the latrines were made of concrete. To use the latrine, a person would walk the forty or fifty yards from the barracks, climb a half-dozen steps to a platform divided into five or six spaces that offered the bare minimum of privacy, stood or squatted on two pieces of wood, and contributed to the contents of the large petrol tanks below. From the same relief worker's report of 1941: “Access to lavatories is generally difficult because of the mud surrounding them. They are so poorly maintained and so rarely disinfected that not only is there a dreadful stink but also a permanent risk of infection, especially during the hot season when flies and mosquitoes proliferate and spread contagious diseases. Rodents have appeared, which besides attacking the food reserves also carry harmful bacteria.”

When the first internees arrived at the newly organized accommodation center of Rivesaltes in January 1941, they found the water pipes frozen and, thus, access to showers nonexistent. This obstacle to cleanliness persisted even with the arrival of warmer weather, as there were few washbasins and the flow of water was frequently interrupted. For weeks, those trapped within the barbed wire were only rarely able to wash themselves and even then, hastily and incompletely. Another eyewitness account declared, “Some internees have not undressed for six months. One can only imagine their present state of destitution.”

The consequences of living in crowded, unhealthy living quarters with a seriously inadequate diet and almost total lack of hygiene quickly manifested themselves. Many prisonersâfor that is what they wereâsoon fell ill. Cases of tuberculosis, dysentery, and enteritis, on top of simple malnutrition and exposure, swept through the camp. Many prisoners died in the arms of family members or, even more wretchedly, alone on their mattresses of straw. Medical facilities within the camp,

not surprisingly, were insufficient. Severe cases were occasionally moved to the St. Louis Hospital in Perpignan; an exasperated social worker wrote of the institution, “although it resembles the worst medieval general hospitals, it continues to receive patients.”

In August 1941, the U.S. State Department forwarded a memorandum on conditions at Rivesaltesâwritten by a relief worker hired by the American Jewish Congressâto a Monsieur de Chambrun of the Foreign Ministry of the Vichy government. The memo concluded, “No self-respecting zoo-keeper would allow the animals in his care to be housed under the conditions prevailing here.” There is no evidence of any reply from the ministry.

Rivesaltes, it must be said, was not an extermination camp. No one there died by design of the authorities. There were no roll calls, no guard towers, no snarling police dogs, no overt brutality meted out by the French guards. There was at least one instance, reported by a survivor whose testimony was videotaped by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, of a coordinated sexual assault by French soldiers. This witness told of soldiers entering one of the women's barracks and going up and down the center aisle, lifting blankets bunk by bunk to decide which women to take back to their quarters. But for the most part, prisoners were not hounded, harassed, or humiliated.

They were simply left alone in that vast empty space to lean into the constant stiff winds that blew winter and summer, the mistral that stirred up the dust and dirt into little cyclones of torment in the dry season and wrinkled the puddles that covered the endless mud when it rained. They were left alone with no books or newspapers to read, no work to accomplish, no place to walk but on the well-worn path to the latrine, no place to sit but on their bunks in their crowded, uncomfortable barracks, nothing to do but wait or hope or dream increasingly threadbare dreams. Children played with stones and sticks. The days seemed endless . . . and yet they ended far too soon for many prisoners of Rivesaltes.

In August 1942, the Vichy government ordered that part of the camp at Rivesaltes be reorganized as the

Centre National de Rassemblement des Israélites

, or the National Center for the Gathering of Jews. Foreign-born Jews in the Unoccupied Zone were rounded up, brought to Rivesaltes, and temporarily housed in blocks F, J, and K. Beginning on August 11 and continuing until October 20, nine convoys of prisoners, including both these newly “gathered” Jews and those who had been residents of Rivesaltes for the prior two-and-a-half years, were all loaded onto boxcars and cattle cars and shipped to the extermination camps of Eastern Europe.

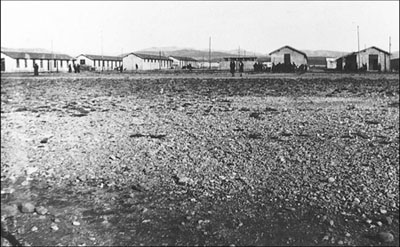

Barracks within the enclosure of Camp Rivesaltes, circa 1941. Today the flat sandy ground is overrun with scrubby stunted evergreens that push their way into what remains of those structures

.

(Courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

During the years 1941 and 1942, about twenty-one thousand internees passed through Camp Rivesaltes. More than two hundred died in the camp, including fifty-one children aged one year or younger. More than twenty-three hundred were shipped to their slaughter.

In November 1942, the German army invaded the Unoccupied Zone and, finding the camp no longer useful for its murderous purposes, ordered the closing of Rivesaltes on November 25. But nearly two years later, after the liberation of France, Rivesaltes was reopened as Camp 162 to house German and Italian prisoners of war. During the following two years, nearly ten thousand inmates lived there. As proof that the harshness

of the camp's climate respected no national boundaries, more than four hundred POWs died in the camp before it was closed again in 1946.

But the unhappy history of Camp Rivesaltes was far from complete. Beginning in 1954, France waged an eight-year war against the independence-minded population of Algeria, which had existed as a French colony for more than a hundred years. Within that country, there was a sizable population of Algerians, mostly Muslims, who had fought for the French in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and in both world wars. In the war for Algerian independence, those soldiers, known as Harkis, once more took the side of the French government, and after Algeria secured its independence in 1962, the Harkis were subject to often brutal reprisals from their newly independent countrymen. Many tens of thousands of Harkis were shot, burned alive, castrated, dragged behind trucks, and tortured in other unspeakable ways. Thousands of Harkis fled to France, thinking that the country for which they had fought would shelter them. Instead, the French government refused to recognize the right of these former soldiers to live peaceably within French society and confined more than twenty thousand Harkis behind the same barbed wire fences in Camp Rivesaltes that had imprisoned the Jews twenty years earlier.

Even in the twenty-first century, Rivesaltes has served as a prison for “undesirables.” As recently as 2007, the better-preserved barracks were home to immigrants, many of them also Muslim and in the country without proper papers. The camp, constructed as a base for the French army to prepare for the defense of its homeland, has instead largely served as a place of misery and anguish for nearly eighty years.

O

NE OF THE FIRST PIECES

of documentary evidence from my grandfather and uncle's long, sad journey through France that found its way into my hands is a list of Rivesaltes detainees that I discovered among the holdings of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. Listed above such names as Szpitzman, Lippmann, Stern, Levy, and Wiesenfelder, Alex and Klaus Goldschmidt were among twenty men who entered the gate of Camp de Rivesaltes on January 14, 1941âthe

date it officially opened as an accommodation centerâand were assigned to Block K, Barracks No. 21. A dossier was filled out for each of themâNo. 222 for Alex and No. 223 for Klaus Helmutâlisting their names, the city of their birth (misspelled in Alex's case), their nationality (German), their religion (“Israelite”), their marital status, and their profession (“salesman” and “student,” respectively).

For six months, they survived the brutal cold, the never-ending mistral winds that Alex declared sapped his strength, the flies and vermin, the suffocating boredom that was only occasionally leavened by letters from his wife and children, and the wretched, inadequate food. Neither of them was particularly robust to begin with, and they both lost considerable weight during their time in Rivesaltes. Alex's weight dropped from 136 pounds to 104, Helmut's from 127 pounds to just 94. By the time spring came to the Pyrenees and the chill of their barracks gave way to oppressive heat, Alex feared that they would not live to see another winter. His apprehension was intensified by the brutal evidence of his immediate surroundings. In a letter written to my father in early 1942, Alex declared, “We saw people literally dying of hunger before our eyes.”

Partly to pass the time and partly to earn a small salary that might aid them in acquiring more and better food, Helmut took a job in the camp infirmary, first as an assistant and later as a medical orderly. In that same letter, Alex reported that “part of Helmut's job was to transfer the deadâsometimes 2 or 3 a dayâand carry the bodies out. These were men who, had they had some degree of nourishment, would not have died.”

In his own letter to his older brother, written the following spring, Helmut recounted his days and nights in Block F, the Rivesaltes camp hospital. Given the severe deprivations he and his father faced daily during their imprisonment, I'm struck by the ironic, sometimes almost playful tone my uncle struck in his narrative. Since I never knew him, of course, his words are all I have to form an impression of his character. I must say that I find him very appealing.

First, along with two Spaniards, I was what one could best describe as a “Girl Friday” in the three barracks that served as the infirmary. Then I was “promoted” and made responsible for

cleanliness. I had to make the beds of the seriously ill patients (Careful! Lice!), distribute medicine (“pill giver”), take patients' temperatures, etc. Part of my job took place in the operating room: I served as the

Infirmius

, in cases of death to help carry off the dead, which was almost a daily occurrence. I also became adept at helping with bandaging. In dealing with sick people I learned a lot, but it was truly not easy. There were two main reasons that prompted me to stay in the job: 1) I didn't want to and couldn't do without the meager pay, and 2) I saw no other way to stay out of the Jewish Tent where I visited Father every evening while he was ill. There the care and treatment were even worse. Of course, I didn't get fat in Block F either.

During those first six months of 1941, as Helmut and Alex struggled to stay alive in Rivesaltes, their dire situation was somewhat ameliorated thanks to the successful attempts of three family members to achieve what they had failed to do: attain freedom in America. The first to make the crossing were Johanna Behrens, the sister of Alex's wife, Toni, and Johanna's husband, Max Markreich. Max and Johanna emigrated to the West in 1939, spent months in a displaced persons facility in Trinidad, and finally reached safe haven in the United States in January 1941. Immediately, Max began writing letters on behalf of his relatives and some friends he had made during his time in the West Indies. He wrote to the Mizrachi Organization of America to request that a tallith (a traditional prayer shawl) and a set of prayer books, with texts in both Hebrew and English, be sent to the camp he'd recently left in Port of Spain, Trinidad. And on March 17, he wrote an impassioned letter to a New York Jewish relief organization called the National Refugee Service with regard to Alex and Helmut. “Dear Sirs,” the letter begins,

Alex Goldschmidt is my brother in law, he emigrated together with his son in May 1939 to Cuba, but they could not be landed, because the emigrants on the S/S “St. Louis” got no permits for debarcation. So they returned again to Europe and my relatives came to France, where they have been placed at once

in an internment camp. Since that time they changed their stay at several times, and according to a letter which I received just now from Mrs. Goldschmidt (Berlin) they are now in the camp: Ilot K, Bar. 21, Camp Rivesaltes, Pyr. Orientales.