All the King's Cooks (14 page)

Read All the King's Cooks Online

Authors: Peter Brears

In lent season porray [leeks] be bold.

On the opposite side of the Paved Passage, to the north between the dry larder and the main kitchens, were two rooms, each having a wide fireplace with a small oven set to one side of it (nos 30–31). In 1674 these were listed as the comptroller’s and master of horse’s kitchens, but this must be a later usage. From their position and their facilities, it is obvious that in the 1530s–40s they were the workhouses for the adjacent hall-place kitchen. These smaller kitchen workhouses were ideal for carrying out the more delicate cookery procedures, particularly the making of hot sauces which formed an integral part of many major dishes, and the better-quality small-scale roasting and baking. Unfortunately, there are neither inventories nor written descriptions to tell us how they were equipped and used. However, it is possible to make informed suggestions by comparing them with the contemporary commercial kitchens probably operating on a similar scale.

The ovens, for example, would be used exactly like those in the bakehouse and pastry and so could turn out dozens of small pastries and tarts. As for the fireplaces, they would appear to be unsuitable for full-scale roasting fires, particularly in view of the relatively small size of the rooms. Probably they would have had raised masonry hearths, where the cooking could take place at a convenient table-top height. As in the seventeenth to mid nineteenth century royal kitchens, they may have incorporated charcoal stoves. The seventeenth century charcoal stoves that still survive in the hall-place kitchen, presumably the very same that were used by great royal cooks such as Patrick Lamb, First Master Cook in the King’s Kitchen from 1688 to 1709, perfectly

illustrate their construction. Built of brick, they have a number of arched recesses set into their vertical fronts. Every other arch is simply a bunker for holding supplies of fresh charcoal, but the ones in between have square ducts going off to each side, each duct bridged by parallel rows of square wrought-iron firebars a few inches from the worktop. These form the bases of circular firepits, which held the burning charcoal. The fuel drew up a strong draught from below, while the ashes fell directly down into the empty arches beneath.

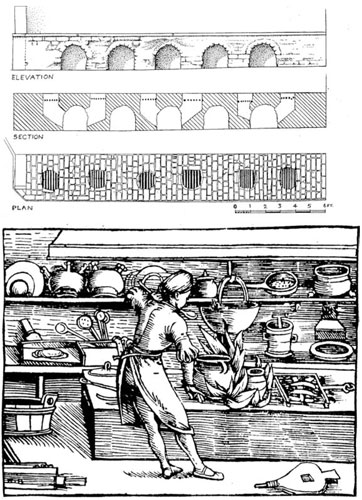

23.

Charcoal stoves

These seventeenth century charcoal stoves (top) in the hall place kitchen are probably very similar to those used by the Tudor cooks. As the cross-section shows, three of the open arches have pairs of combined draught- and ash-holes serving the six fireplaces on the top, so that the fuel could burn with a clear, fierce heat. The other two arches formed convenient bunkers for fresh charcoal.

Hans Burgkmair’s woodcut published in 1542 (bottom) shows a charcoal stove in use for boiling and broiling. Other interesting features include a chopping board with raised sides, cast-bronze cooking pots, a mortar and pestle and, to the right, a typical wooden salt-box with a sloping, hinged lid.

24.

High-level roasting

Town cook-shops used table-height roasting ranges, as seen in Hoefnagel’s painting,

The Marriage Feast at Bermondsey

(1). Here the turnbroach operates two spits at once, like his late fifteenth century Italian counterpart at the Castello d’lssogne (2). Since this was the standard commercial practice of the period, it may have been adopted by cooks working in the royal household. They probably used jacks, too, like the one in drawing 3, based on a woodcut from

Kuchenmeisterei

(printed by Froschauer, Augsburg, 1507), and a drawing based on Bartolommeo Scappi’s illustrations of 1570 (4). A jackshaft (5) was excavated from a cellar dated to 1507 in Norwich. The chicken roasting in the woodcut from Marx Rumpolt’s

Ein Neu Kochbuch

of 1581 (6) is being turned by a rope driven from the smoke-jack in the chimney above.

These stoves are far superior to any modern barbecue, burning efficiently with a steady, clear heat ideal for boiling or frying, and immeasurably more practical for undertaking the more delicate aspects of cookery than the great open hearths of the adjacent kitchens. They are very clean to use, too, their combustion gases leaving only a light coat of ash on the bases of the cooking vessels, and producing no visible smoke. Under normal conditions, when the fumes are drawn straight upwards, these stoves present the cook with few problems, but when sudden draughts direct the invisible gases into his face the effects are devastating – rather like being punched on the nose by a scorching phantom boxing glove, leaving one gasping for breath, eyes watering and nostrils burning. Since the open top of each firepit was its effective chimney, pans could not be placed directly over it or the fire would be stifled. Instead, a triangular wrought-iron trivet with three legs a few inches high was used to support the cooking vessels; this also had the advantage of leaving the fire open to view, so that it could be poked to shake out the ash or have fresh charcoal added whenever necessary.

With cooking facilities like these, along with all the smaller implements such as the graters, sieves, spice-boxes, salt-boxes, bowls, knives, spoons, skimmers, mixing bowls, cooking pots and frying pans, the palace cooks would be fully equipped to perform the tasks allotted them by the clerk of the kitchen.

The Hall-place and Lord's-side Kitchens

Boiling, Broiling, Roasting

At the east end of the Paved Passage lie the great kitchens â two huge rooms, each measuring forty feet (12m) up to the ridge of their arch-braced wooden roofs. These are the most impressive rooms in the whole suite of kitchen offices, and provide ample visual evidence of the importance of the kitchens within the royal household.

The chief cook was John Bricket. Although he was entitled âthe King's master cook', his responsibilities extended far beyond the King's Privy Kitchen to embrace the operation of the whole kitchen complex, from the larder doors through to the dresser hatches where the food was despatched to the dining areas. He was a man of considerable importance: the King granted him the stewardship of Caversham in Oxfordshire and an annuity for life from the issues (tax income) of the counties of Cheshire and Flint, in addition to his wages.

1

Along with his other duties, he had to get rid of all âcorruption and uncleanesse ⦠which doth ingender infection, and is very noisome and displeasant unto all noblemen and others' coming to court.

2

More especially he had to prevent the scullions, or junior kitchen staff, from going ânaked or in garments of such vilenesse as they now doe, and have been accustomed to doe, nor

lie in the nights and dayes in the kitchens or ground by the fireside'. From 1530, such practices â which must surely have befouled the kitchens and everything that passed through them â were banned. From now on the scullions had to be selected from candidates who might reasonably be expected to become cooks, and they were trained with this in mind. Instead of sleeping warm and cosy by the fireside, they were probably sent up to the garrets over the rooms to the north of the Paved Passage â quarters that I know from personal experience would be freezing cold in winter, and therefore probably very unpopular! In addition, the master cook was now issued with a sum of money each year for providing the scullions with âhonest and whole coarse garments', which were to be kept so clean that their appearance would never cause offence. In 1541, he was given £50 âfor appareling of 33 galapines [scullions] for one year fully to be run at Christmas next coming'.

3

The palace's perceptive management policies extended to making sure that not only were the kitchen staff always supplied with clean and adequate clothing, and personally clean, but that, by making them clean up the courtyards and passages around the palace, they also had the opportunity for some healthy outdoor exercise. The household ordinances instructed that the âsaid scullions, a certain number alternately to be deputed, shall daily, once in the forenoone and once in the afternoone, sweepe and make cleane the courts, outward galleryes, and other places of the court, so there remaine no filfth or uncleannesse in the same', to the satisfaction of the sergeant of the hall. The sum of £55 allotted for 33 such âgalapines' shows that they received each year clothing costing, on average, £1 13s 4d each. In contrast Pero Doulx, the French yeoman cook for the King's mouth, received six times as much â £10 a year â for his clothing, in addition to his wages of £13 16s 8d, reflecting his much higher status.

4

To keep themselves clean and tidy, the cooks wore white linen aprons, which were fairly short; and wide in comparison to those worn today. The quality of the fabric varied according to the status of the wearer. Presumably they were very similar to those worn by the junior staff in the Counting House, where on the four great feasts of the year the sergeant received 7 feet 6 inches (2.3 metres) of linen costing about 9½d a yard, the yeomen 3 feet 9

inches (1.1 metres) costing about 6½d a yard, and the groom the same amount at 5d a yard.

5

If it came in 18-inch (46cm) widths, this would make up a pair of aprons nearly two feet (60cm) wide and a foot and a half (46cm) deep, which would look similar to those worn by the cooks in sixteenth-century illustrations.

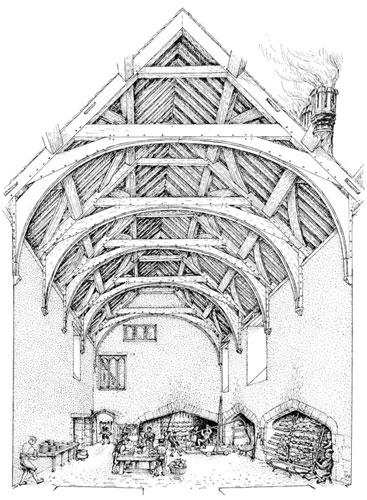

25.

â

The Hall-place Kitchen

Built for Henry VIII about 1530, this kitchen prepared all the food for the lesser courtiers and household officers who dined in the Great Hall. Raw food came in from the larders at the end, was cooked in the fireplaces, then served through the hatches in the left-hand wall.

Although the administrators of Henry VIII's household left ample documentary evidence of their activities, his cooks left virtually none. They were certainly very experienced professionals: the written descriptions of the great feasts they prepared show that they were capable of achieving the highest of international standards. To give us some impression of the hall-place and Lord's-side cookery, we have only three contemporary sources, of which is anywhere near as complete as we might wish. The first is the âdietary' of the court, which forms part of the household ordinances.

6

It lists the dishes served to each division of the household, and sometimes gives brief details of the way they were cooked. The second is the body of high-class recipes recorded in a late fifteenth century manuscript which includes dishes cooked by one of Henry VIII's sergeant cooks.

7

The third is a group of cookery books published from the mid sixteenth century for the use of noble and upper-class wives.

8