All the King's Cooks (18 page)

Read All the King's Cooks Online

Authors: Peter Brears

33.

Kitchen equipment

This selection shows skimmers on their rack (1), a hair sieve (2), and a sheath of cook’s knives (3) as illustrated by Scappi in 1570. The frying pan (4) was used in Norwich in 1507, the knife (5) in Bristol in 1479, and the cleaver (6) at Northcott Manor, Middlesex, in the early fifteenth century; the salt-box (7) is based on a carving of c.1500 in Manchester Cathedral.

34.

Graffiti

This stag was probably scratched into the masonry at the side of the Hall-place dresser by a Tudor or Stuart cook, and represents the royal venison cooked across in the Privy Kitchen but never officially tasted here.

At a Hampton Court kitchen demonstration two of the visitors were very surprised to see chickens being cooked in this way. It turned out that the method was identical to one that they regularly used at home in Malta. It was fascinating to discover that this recipe, brought to England from the Mediterranean by returning Crusaders some eight hundred years ago, along with so many other fine Arab dishes, was still flourishing today in one of its countries of origin.

In another roast, thin slices of steak were rolled and stuffed to resemble larks, taking their name from

aloe

, the Old French word for this small bird. Today this dish is better known as ‘beef olives’. Probably the most prestigious roast was venison, the dietaries restricting the serving of this meat to the tables of the King and Queen. Andrew Boorde held this meat in the highest esteem:

I am sure it is a lordes disshe, and I am sure it is good for an Englisshe man, for it doth anymate hym to be as he is, whiche is stronge and hardy, but I do advertyse every man, for all my wordes, not to kyll, and so to eate of it, excepte it be [lawfully], for it is a meate for great men. And great men do not set so much by the meate, as they do by the pastyme of kyllyng of it … there is not so moche pleasure for harte & hynde, bucke, and doo, and for roo bucke and doo, as here in Englande.

5

For centuries, the accompaniment to roast venison was frumenty – a sort of whole-wheat porridge which Boorde commended, for, ‘when it is digested it doth nourysshe, and it doth strength a man’.

6

Another roast suitable for the royal table was peacock. Various authors have given peacock a poor reputation, describing it as tough and unpleasant. This may originate in historical references such as this comment in Andrewe’s

Noble Lyfe

: ‘it is evyll flesshe to disiest [digest], for it can nat be rosted or soden ynough’, while Andrew Boorde confirmed that ‘olde pecockes be harde of dygestyon [but] young peachycken of halfe a yere of age by praysed’.

7

The royal cooks certainly appreciated this difference when making their peacock ‘in hakille ryally’ (‘hackle’ being the medieval word for a bird’s skin and plumage), or for ‘a Feesste Roiall’, for which the peacock had its unplucked skin put back in place after being roasted.

8

Whenever this dish is depicted complete with its tail feathers, they are seen to be those of a young, tender bird, not the fully developed ones of an old one.

9

Certainly, modern farmed peacocks eat very well – they have a flavour midway between chicken and pheasant, and large breasts and legs ideal for carving.

In addition to being roasted and boiled, white meats were also served as a ‘mortis’ or ‘blancmange’, a sort of sweet pate thickened with rice flour, breadcrumbs or almonds.

10

It was not until the Victorian period that blancmanges were transformed into the cornflour moulds we now recognize by that name, which simply means ‘white food’.

As for fish, although the King and Queen enjoyed a much greater choice of species, the methods of cookery would have been very similar to those used in the hall-place and Lord’s-side

kitchens. They would also have enjoyed superior dishes such as mortis or roasts of the most delicate fishes.

The King was also served with puddings, these being largely meat or cereal mixtures cooked in skins, just like the black puddings, hog’s puddings and haggises which still survive from medieval times. Probably because she had a good reputation for her puddings, ‘the wif that makes the king podinges at hamp-toncourte’ was paid 6s 8d from the Privy Purse expenses.

11

She probably worked outside the royal household, bringing in her wares as required. The King’s and Queen’s dietaries included a number of sweet dishes such as custards, fritters, ‘dowcets’, tarts, ‘rascals’, jelly and cream of almonds, all made in the privy kitchen. These dishes, in addition to the fruit – baked pippins, oranges, quinces and so on – provided by the Confectionary, featured in their everyday meals as well as being served at ‘banquets’, those most exclusive of informal entertainments at which sweetmeats and fine wines were served, either in privy chambers or in the banqueting houses which stood in the Privy Gardens to the south of the palace. Some of these dishes were quite plain: ‘rascals’, alias ‘resquyles’, or ‘rysmole’ simply being a ground-rice cream.

Almond cream was similarly bland, but being ‘made with fyne sugar and good rose-water and eaten with the flowers of many vyolettes, is a commendable dysshe, specyallye in Lent, it comfortes the brayne, & doth qua-lyfye the heate of the lyvver’.

12

In contrast, jellies had been among the most spectacular dishes to be made in the royal kitchens for centuries. At the coronation of Henry VI in 1429, for example, there had been ‘Gely party wryten and noted [inscribed] with “Te Deum laudamus”’ and ‘A white leche (see p. 155) wyth a red antelop, with a crowne about his necke with a chayne of golde’.

13

Francesco Chiergato, the apostolic nuncio in England, had marvelled at the jellies that Henry VIII had served to the Spanish embassy in 1517 – ‘but the jellies of some 20 sorts perhaps, surpassed everything, they were made in the shape of castles and animals of various descriptions, as beautiful and admirable as can be imagined’.

14

The original recipes call for calves’ feet and similar gelatinous materials to be boiled, strained and clarified – time-consuming processes that made jellies very expensive to produce – but today they can be made with ready-prepared gelatin to produce identical results. The jelly listed in the Henrician dietary was called ‘jelly ipocras’, since it was essentially a jellified form of the sweet spiced wine of that name:

15

Its flavour contrasted admirably with the other main variety of jelly, the ‘leach’. This word, which simply means ‘slice’, was used to describe a luscious, cool, perfumed mass of translucent whiteness, solid enough to be cut into cubes and lifted to the lips with the fingers.

16

35.

Washing up Washing up in a cauldron mounted on an iron trivet – based on a drawing by the antiquary Thomas Wright of ‘one of the curious wooden sculptures in the church of Kirby Thorpe, in Yorkshire’.

As well as making these and many other ‘banqueting stuffs’, the Privy Kitchen would prepare various hot nightcaps for the royal family. One of these was ‘aleberry’, which was served in the special aleberry bowl listed in the inventory of 1547.

17

For the cooks in all the royal kitchens, the serving of the meals by no means marked the end of their working day, for they had all their dirty pots, pans and spits to clean and scour ready for reuse. To start washing-up, some of the large kettles would have

been filled with water and set over the fire to boil, hot water with either an alkaline lye made from wood ashes or, for more stubborn stains, the fine sand imported from Calais, being used with cloths to clean every utensil. As the fourteenth-century writer John Trevisa had observed, ‘Brazen vessels by soon red and rusty, but they be oft scoured with sand, and have an evil savour and smell but they be tinned. Also brass, if it be without tin, burneth soon.

18

If the scullions cleaned too vigorously the tinning would be quickly removed and the working life of the pots would be considerably shortened:

19

No scouring for pride

Spare kettle whole side

Though scouring be needfull, yet scouring too much

Is pride without profit, and robbeth thine hutch.

Keep kettles from knocks, set tubs out of sun

For mending is costly, and crackt is soon done.

Preparing for Dinner

Pantry and Cellars

When the cooks were busy in the kitchens, numerous other servants were fully occupied with their own preparations, largely in the rooms beneath and around the Great Hall.

In one small room beneath the screens passage (no. 56), cartloads of manchets and cheat loaves from the bread store in the bakehouse would be unloaded by the pages of the pantry.

1

The quality and quantity were then checked by the groom brever, who recorded their number by cutting notches on a split tally-stick, keeping one half for himself, and giving the other to the bakehouse staff. From here the bread was carried up to the pantry on the floor above, where the manchets would be stored in one set of bread bins, and after the pages had used their chipping knives to pare away the tough outer crusts, the cheat loaves into another.

2

One page for the King’s mouth pared the cheat loaves from the privy bakehouse and took them with manchets up to the chambers, while the other pantry staff took the ordinary cheat bread into the Great Hall. In order to see that the bread was efficiently and economically served, the yeomen brever and the pages took their meals in the pantry, and the grooms at the tables just inside the Hall. Next morning at eight the brever had to meet the clerk of the kitchens here, and present him with a precise account of how many loaves had been distributed the previous day.

The provision and serving of all the wines, ales and beers was the responsibility of William Abbott, sergeant of the cellar, constable of Cardigan Castle and keeper of the forest of Radnor.

3

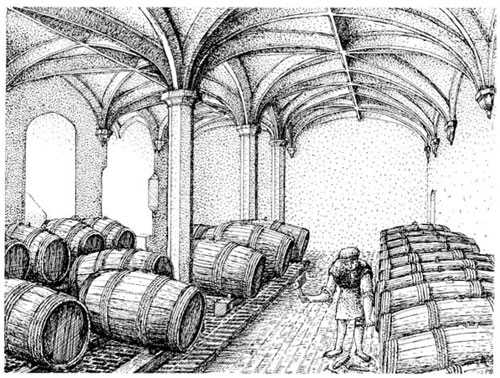

To carry out his work he had three separate departments, the Cellar itself dealing with wine, the Buttery with ale and beer, and the Pitcher House with jugs, cups and serving. The barrels of wine purchased by the purveyors, or received as gifts, were stored either in the great wine cellar (no. 50), or, if for the King’s use, in the adjacent privy cellar (no. 51), where they were checked and accounted for by the purveyors and set up on their stands, or ‘stillages’.

4

Every day the groom grobber checked the barrels, and ensured that none were tapped by the yeoman treyer, unless a clerk comptroller was there to supervise the operation. Using a tarrier, or auger, a hole would be bored, pointing slightly upwards into the vertical end of the barrel, some four fingers’ breadth up from the

bottom of the rim, to receive a cannel, or tap. A gimlet was then used to pierce a smaller hole in the top of the barrel, into which a faucet or peg was driven.

5

This allowed air to enter as the wine was drawn off by the treyer, before he delivered it to the bar at the cellar door.

6