All the King's Cooks (17 page)

Read All the King's Cooks Online

Authors: Peter Brears

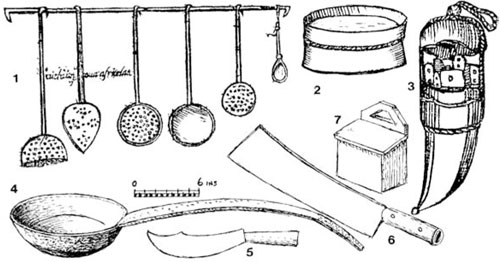

30.

â

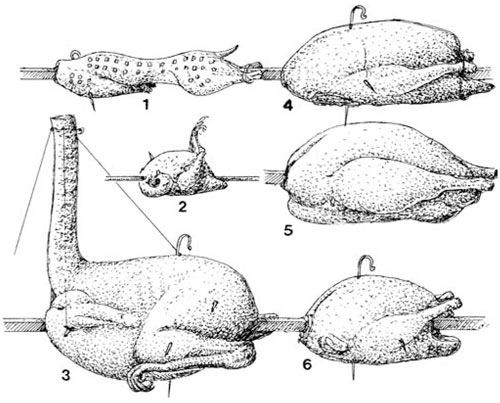

Trussing

Tudor recipe books give detailed instructions for trussing meat for the spit: rabbits were parboiled and larded (1); snipe had their bills stuck through their shoulders (2); peacocks had their legs folded and necks set erect (3); and ducks, geese and chickens had their wings and lower legs removed (4â6).

They usually carry a health warning, such as âbeware of saledis, grene metis, & frutes rawe, for they make many a man have a feble mawe', or âbeware of grene sallettes & rawe fruytes, for they wyll make your sovrayne seke [sick]'.

18

All the same, there had been a long tradition of eating salads in England. One royal recipe of 1393 included parsley, sage, garlic, spring onions, leek, borage, mint, fennel, garden cress, rue, rosemary and purslane, to be washed, picked clean, mixed with olive oil and sprinkled with vinegar and salt. In the sixteenth century similar salads were being made in an almost identical way, except that lettuces were included and the salt was replaced with sugar. Simple salads now contained lettuce dressed with oil, vinegar and sugar, or cold boiled onions, asparagus or samphire, or cucumbers dressed with oil, vinegar and pepper.

The meals would have been served from the dresser hatches into the Great Space, where waiters would carry them a few paces to the dresser office for checking by the clerks, before taking them up to the Great Watching Chamber. Dishes such as these, along with the rich meat pies and fruit tarts from the Bakehouse, would have provided the senior courtiers and senior household staff with excellent fare.

31.

â

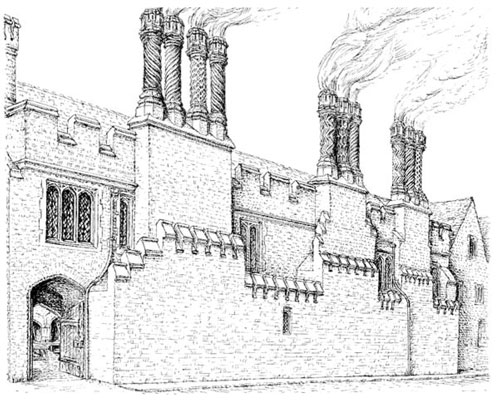

The kitchen chimneys

The north wall of the kitchens, facing on to Tennis Court Lane, is a magnificent example of early-sixteenth-century brickwork. The wide doorway provides the only access into the kitchens from the north, and was essential for bringing in the tons of logs required to keep the ten great fireplaces constantly ablaze in the kitchens and workhouses.

At the east side of the Great Space, next door to the Lord's-side kitchen-workhouse, were two rooms (no. 46) used as lodgings by the clerk of the kitchen, a spiral staircase in one corner leading up to the first-floor chambers (no. 47). These rooms were occupied by the Queen's groom porter, the officers of the Wafery, and the master surgeon and yeoman surgeon, together with their groom and either a servant or an âhonest child'.

19

While it was the doctor

of physic who advised on the King's diet, concocted his medicines and sought out lepers and those with contagious diseases at court, the surgeons were responsible for all the more practical aspects of health care.

20

As well as carrying out actual surgery, they received an allowance of âbroken meats' left over after meals, which presumably included fats for ointments, bread for poultices and so on. Worn-out cloths and towels from the Ewery they used to make bandages and plasters for sick officers of the court. Some of these items, together with medicines for the King's use, were stored in these chambers in a small coffer.

Details of the organisation of a surgical operation at court, and the roles played by the kitchen staff, appear in an account of the trial of Sir Edmund Knevet, held at Greenwich on 10 June 1541.

21

Having been found guilty of striking one Master Clere at the King's court, Sir Edmund was sentenced to lose his right hand, and so the appropriate officers were assembled. The yeoman of the scullery brought two forms to hold the equipment: the sergeant of the woodyard brought his mallet and chopping block, the King's master cook brought his knife â and the sergeant of the poultry brought a cock which would have its head cut off with these items so as to check that they were in good order. The sergeant of the larder, with his great knowledge of butchery, was there to set the knife in the best position on the wrist, and the sergeant farrier brought his searing irons â for sealing the veins â these first being heated in a chafing dish and their ends cooled in a dish of water brought by the yeoman of the scullery. The sergeant surgeon was in attendance with his instruments to close up the wound, which would then be dressed with âsear-cloth' brought by the yeoman of the chandlery. In addition, the sergeant of the cellar brought wine, ale and beer, and the yeoman of the ewery, deputising for his sergeant, brought a ewer, a basin and towels for hand-washing.

Fortunately, Sir Edmund's appeal to the King was successful, and he both kept his hand and received a full pardon. But this description clearly shows how closely the surgeons and the household staff were expected to work together, and suggests how useful they would all be when on active military service.

32.

â

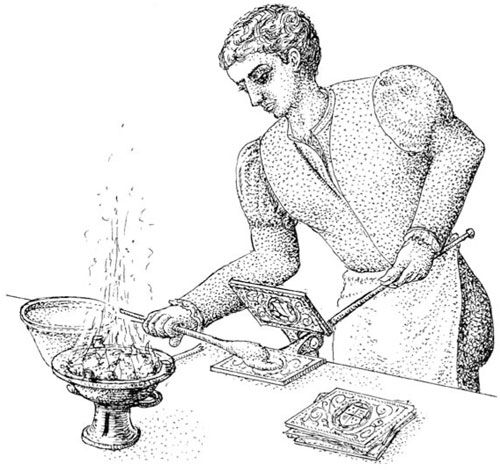

Wafers

Here iron wafer-tongs cut with the Tudor royal arms are being filled with an egg, flour, sugar and rosewater batter before being cooked over the chafing dish.

The last room in this first-floor area that should be mentioned is

the Wafery. This office produced wafers â broad discs or rectangles of thin, crisp, delicately-flavoured biscuit, made only for the King, dukes, earls, the White Sticks, the cofferer, and a privileged few as authorised by the Counting House. Lesser mortals might only enjoy them at the four great feasts of the year.

22

The yeoman of the wafery, assisted by a groom skilled in wafer-making and, at the discretion of the Counting House, a page to learn the craft and give general assistance, were solely responsible to the clerk of the spicery. The sugar, eggs and baking irons they needed came from the Spicery, while the flour was obtained from the sergeant of the bakehouse either daily or weekly. A sweet spiced batter would be made, then small quantities ladled on to the âirons' â flat plates engraved with various patterns and mounted on long handles like tongs â which had been pre-heated over a charcoal-

fired chafing dish. Having closed the irons together, the batter cooked rapidly, sending jets of rosewater steam spouting from the edges. After this, the irons were opened, and the crisp wafers removed. The newly baked wafers would be carefully locked away in fine coffers. When the time came, they would be delivered to the sewer of the privy chamber, for the King's mouth; to the sewers of the presence chamber, for distribution as directed by the Counting House; or to the sewer of the hall â to be served there only on the important feast days.

The Privy Kitchen

Food for the King

The hall-place and Lord’s-side kitchens were designed to serve the household servants and the courtiers with their main meals at ten and four o’clock each day, the vast scale of their operations making any unexpected changes in their routines extremely difficult to manage. It would therefore have been impossible for them also to meet the needs of a monarch, especially one as mobile as Henry VIII, who was usually unwilling to return to the palace ‘upon the time prefixed for dinner and souper’, particularly if he had ‘gone further in walkeing, hunting, hawking, or other disports’.

1

These activities made it essential for him to be served by a separate office, the Privy Kitchen. Flexibility of mealtimes was only one of the advantages of this arrangement; perhaps more importantly, it also protected him from the risk of poisoning, ensured the security of the rarest and most expensive of foodstuffs in the kitchen, and enabled the King’s personal cooks to create the finest of dishes in kitchens that were entirely under their own control. In addition, special diets could be prepared for the King and the closest members of the royal family, as advised by the physician.

In the 1540s the King’s privy kitchen was located beneath his Long Gallery in the wing separating the present Clock Court and Fountain Court; the Queen’s privy kitchen, built in 1533 for Anne Boleyn, was beneath her Presence Chamber, midway

between the chapel and Fountain Court.

2

In these positions the two kitchens were ideally situated to provide hot food directly to the rooms in which the King and the Queen took their meals, as well as keeping their personal apartments extra-warm and comfortable. Working from the dietaries of the King and Queen it is possible to make informed suggestions as to the dishes prepared here by Pero, the French cook to the King’s mouth, and his fellows.

3

The foods prepared for the King were particularly rich and flavoursome. They included a large number of delicious pottages of meat, fish and vegetables. One was of particular interest, since it took a fresh-killed chicken, made a cut in the back of its neck into which the cook blew hard, inflating the skin like a balloon to separate it from the flesh. Once the chicken had been drawn, washed and had its head removed, the space between the skin and the flesh was packed with a rich stuffing, which was first set in place by parboiling. Then the chicken was lifted from the pot and spit-roasted before the fire. As it rotated, the fats and flavours of the stuffing permeated the chicken, while its juices were encased inside the stuffing layer. The result was the most succulent and delicious of dishes.

4