Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (54 page)

Read Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder Online

Authors: Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Another illustration, this time a situation that benefits from variation—positive convexity effects. Take two brothers, Castor and Polydeuces, who need to travel a mile. Castor walks the mile at a leisurely pace and arrives at the destination in twenty minutes. Polydeuces spends fourteen minutes playing with his handheld device getting updates on the gossip, then runs the same mile in six minutes, arriving at the same time as Castor.

So both persons have covered the exact same distance, in exactly the same time—same average. Castor, who walked all the way, presumably will not get the same health benefits and gains in strength as Polydeuces, who sprinted. Health benefits are

convex

to speed (up to a point, of course).

The very idea of exercise is to gain from antifragility to workout stressors—as we saw, all kinds of exercise are just exploitations of convexity effects.

We often hear the expression “small is beautiful.” It is potent and appealing; many ideas have been offered in its support—almost all of them anecdotal, romantic, or existential. Let us present it within our approach of

fragility

equals

concavity

equals

dislike of randomness

and see how we can measure such an effect.

A squeeze occurs when people have no choice but to do something, and do it right away, regardless of the costs.

Your other half is to defend a doctoral thesis in the history of German dance and you need to fly to Marburg to be present at such an important moment, meet the parents, and get formally engaged. You live in New York and manage to buy an economy ticket to Frankfurt for $400 and you are excited about how cheap it is. But you need to go through London. Upon getting to New York’s Kennedy airport, you are apprised by the airline agent that the flights to London are canceled, sorry, delays due to backlog due to weather problems, that type of thing. Something

about Heathrow’s fragility. You can get a last-minute flight to Frankfurt, but now you need to pay $4,000, close to ten times the price, and hurry, as there are very few seats left. You fume, shout, curse, blame yourself, your upbringing and parents who taught you to save, then shell out the $4,000. That’s a squeeze.

Squeezes are exacerbated by size. When one is large, one becomes vulnerable to some errors, particularly horrendous squeezes. The squeezes become nonlinearly costlier as size increases.

To see how size becomes a handicap, consider the reasons one should not own an elephant as a pet, regardless of what emotional attachment you may have to the animal. Say you can afford an elephant as part of your postpromotion household budget and have one delivered to your backyard. Should there be a water shortage—hence a squeeze, since you have no choice but to shell out the money for water—you would have to pay a higher and higher price for each additional gallon of water. That’s fragility, right there, a negative convexity effect coming from getting too big. The unexpected cost, as a percentage of the total, would be monstrous. Owning, say, a cat or a dog would not bring about such high unexpected additional costs at times of squeeze—the overruns taken as a percentage of the total costs would be very low.

In spite of what is studied in business schools concerning “economies of scale,” size hurts you at times of stress; it is not a good idea to be large during difficult times. Some economists have been wondering why mergers of corporations do not appear to play out. The combined unit is now much larger, hence more powerful, and according to the theories of economies of scale, it should be more “efficient.” But the numbers show, at best, no gain from such increase in size—that was already true in 1978, when Richard Roll voiced the “hubris hypothesis,” finding it irrational for companies to engage in mergers given their poor historical record. Recent data, more than three decades later, still confirm both the poor record of mergers and the same hubris as managers seem to ignore the bad economic aspect of the transaction. There appears to be something about size that is harmful to corporations.

As with the idea of having elephants as pets, squeezes are much, much more expensive (relative to size) for large corporations. The gains from size are visible but the risks are hidden, and some concealed risks seem to bring frailties into the companies.

Large animals, such as elephants, boa constrictors, mammoths, and

other animals of size tend to become rapidly extinct. Aside from the squeeze when resources are tight, there are mechanical considerations. Large animals are more fragile to shocks than small ones—again, stone and pebbles. Jared Diamond, always ahead of others, figured out such vulnerability in a paper called “Why Cats Have Nine Lives.” If you throw a cat or a mouse from an elevation of several times their height, they will typically manage to survive. Elephants, by comparison, break limbs very easily.

Let us look at a case study from vulgar finance, a field in which participants are very good at making mistakes. On January 21, 2008, the Parisian bank Societé Générale rushed to sell in the market close to seventy billion dollars’ worth of stocks, a very large amount for any single “fire sale.” Markets were not very active (called “thin”), as it was Martin Luther King Day in the United States, and markets worldwide dropped precipitously, close to 10 percent, costing the company close to six billion dollars in losses just from their fire sale. The entire point of the squeeze is that they couldn’t wait, and they had no option but to turn a sale into a fire sale. For they had, over the weekend, uncovered a fraud. Jerome Kerviel, a rogue back office employee, was playing with humongous sums in the market and hiding these exposures from the main computer system. They had no choice but to sell, immediately, these stocks they didn’t know they owned.

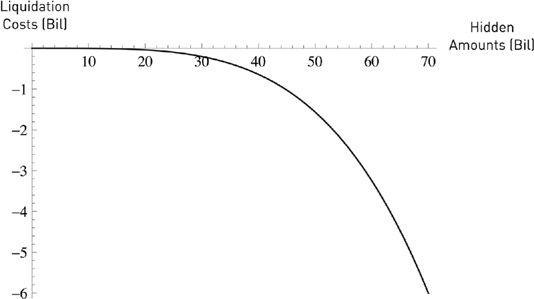

Now, to see the effect of fragility from size, look at

Figure 15

showing losses as a function of quantity sold. A fire sale of $70 billion worth of stocks leads to a loss of $6 billion. But a fire sale a tenth of the size, $7 billion would result in no loss at all, as markets would absorb the quantities without panic, maybe without even noticing. So this tells us that if, instead of having one very large bank, with Monsieur Kerviel as a rogue trader, we had ten smaller banks, each with a proportional Monsieur Micro-Kerviel, and each conducted his rogue trading independently and at random times, the total losses for the ten banks would be close to nothing.

FIGURE 15.

Small may be beautiful; it is certainly less fragile. The graph shows transaction costs as a function of the size of the error: they increase nonlinearly, and we can see the megafragility.

About a few weeks before the Kerviel episode, a French business school hired me to present to the board of executives of the Societé Générale meeting in Prague my ideas of Black Swan risks. In the eyes of the bankers, I was like a Jesuit preacher visiting Mecca in the middle of the annual Hajj—their “quants” and risk people hated me with passion, and I regretted not having insisted on speaking in Arabic given that they had simultaneous translation. My talk was about pseudo risk techniques à la Triffat—methods commonly used, as I said, to measure and predict events, methods that have never worked before—and how we needed to focus on fragility and barbells. During the talk I was heckled relentlessly by Kerviel’s boss and his colleague, the head of risk management. After my talk, everyone ignored me, as if I were a Martian, with a “who brought this guy here” awkward situation (I had been selected by the school, not the bank). The only person who was nice to me was the chairman, as he mistook me for someone else and had no clue about what I was discussing.

So the reader can imagine my state of mind when, shortly after my return to New York, the Kerviel trading scandal broke. It was also tantalizing that I had to keep my mouth shut (which I did, except for a few slips) for legal reasons.

Clearly, the postmortem analyses were mistaken, attributing the

problem to

bad

controls by the

bad

capitalistic system, and lack of vigilance on the part of the bank. It was not. Nor was it “greed,” as we commonly assume. The problem is primarily size, and the fragility that comes from size.

Always keep in mind the difference between a stone and its weight in pebbles. The Kerviel story is illustrative, so we can generalize and look at evidence across domains.

In project management, Bent Flyvbjerg has shown firm evidence that an increase in the size of projects maps to poor outcomes and higher and higher costs of delays as a proportion of the total budget. But there is a nuance: it is the size per segment of the project that matters, not the entire project—some projects can be divided into pieces, not others. Bridge and tunnel projects involve monolithic planning, as these cannot be broken up into small portions; their percentage costs overruns increase markedly with size. Same with dams. For roads, built by small segments, there is no serious size effect, as the project managers incur only small errors and can adapt to them. Small segments go one small error at the time, with no serious role for squeezes.

Another aspect of size: large corporations also end up endangering neighborhoods. I’ve used the following argument against large superstore chains in spite of the advertised benefits. A large super-megastore wanted to acquire an entire neighborhood near where I live, causing uproar owing to the change it would bring to the character of the neighborhood. The argument in favor was the revitalization of the area, that type of story. I fought the proposal on the following grounds: should the company go bust (and the statistical elephant in the room is that it eventually will), we would end up with a massive war zone. This is the type of argument the British advisors Rohan Silva and Steve Hilton have used in favor of small merchants, along the poetic “small is beautiful.” It is completely wrong to use the calculus of benefits without including the probability of failure.

2

Another example of the costs of a squeeze: Imagine how people exit a movie theater. Someone shouts “fire,” and you have a dozen persons squashed to death. So we have a fragility of the theater to size, stemming from the fact that every additional person exiting brings more and more trauma (such disproportional harm is a negative convexity effect). A thousand people exiting (or trying to exit) in one minute is not the same as the same number exiting in half an hour. Someone unfamiliar with the business who naively

optimizes

the size of the place (Heathrow airport, for example) might miss the idea that smooth functioning at regular times is different from the rough functioning at times of stress.

It so happens that contemporary economic optimized life causes us to build larger and larger theaters, but with the exact same door. They no longer make this mistake too often while building cinemas, theaters, and stadiums, but we tend to make the mistake in other domains, such as, for instance, natural resources and food supplies. Just consider that the price of wheat more than tripled in the years 2004–2007 in response to a small increase in net demand, around 1 percent.

3

Bottlenecks are the mothers of all squeezes.

Let us start as usual with a transportation problem, and generalize to other areas. Travelers (typically) do not like uncertainty—especially when they are on a set schedule. Why? There is a one-way effect.

I’ve taken the very same London–New York flight most of my life. The flight takes about seven hours, the equivalent of a short book plus a

brief polite chat with a neighbor and a meal with port wine, stilton cheese, and crackers. I recall a few instances in which I arrived early, about twenty minutes, no more. But there have been instances in which I got there more than two or three hours late, and in at least one instance it has taken me more than two days to reach my destination.

Because travel time cannot be really negative, uncertainty tends to cause delays, making arrival time increase, almost never decrease. Or it makes arrival time decrease by just minutes, but increase by hours, an obvious asymmetry. Anything unexpected, any shock, any volatility, is much more likely to extend the total flying time.

This also explains the irreversibility of time, in a way, if you consider the passage of time as an increase in disorder.

Let us now apply this concept to projects. Just as when you add uncertainty to a flight, the planes tend to land later, not earlier (and these laws of physics are so universal that they even work in Russia), when you add uncertainty to projects, they tend to cost more and take longer to complete. This applies to many, in fact almost all, projects.