Read Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse Online

Authors: David Maislish

Tags: #Europe, #Biography & Autobiography, #Royalty, #Great Britain, #History

Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse (11 page)

At last, with the battle all but over, Prince Edward arrived with his men. Seeing the disaster before them, the majority turned and fled, leaving Edward to take refuge in a friary. The following day, surrender terms were agreed, with the royal army laying down their arms and the King and Prince Edward taken prisoner. No physical harm was done to either of them, because Simon and his supporters were monarchists; it was just that they wished to limit the monarch’s powers as agreed at Oxford.

With the King under rebel control, the country was governed by the Earl of Leicester (that is, Simon de Montfort), the Earl of Gloucester (Gilbert de Clare) and the Bishop of Chichester (much of the clergy having supported the rebels in their moral crusade).

They summoned a parliament in 1265 that was made up of 23 barons, two knights from each county and two citizens and burgesses from each of the major towns and boroughs. With part non-nobility non-clergy membership for the first time, this was the origin of the House of Commons.

As always, one man became the absolute ruler. Simon began to govern as a dictator. With the King now a figurehead and a dictator in power, the mood of the barons and the populace changed. Gloucester withdrew to his estates. Then, one day when he was out riding, Prince Edward escaped from confinement. He rushed to join Gloucester and the others opposed to Simon’s rule.

Ten weeks later, at the brutal Battle of Evesham, the two sides met once more. King Henry was at the battle, still in the custody of Simon and his knights as they fought in a circle around him. As Simon and his colleagues were slaughtered in the effort to kill all the Montfortian leaders, one of Prince Edward’s knights, not realising whom he was attacking, struck Henry across the face with a sword, knocking the King to the ground. By pure chance, Henry was not killed. Looking up, the desperate Henry, bleeding severely from the face, screamed out, referring to his birthplace, “I am Henry of Winchester, your king! I am Henry your king!”. The attacker held back, and Henry was rescued and removed from danger as the battle came to an end.

Surrender by traitors did not lead to a negotiated peace. Most Montfortians not already killed were butchered after the battle. Simon was dead, so when the fighting ended, his corpse was decapitated, his private parts cut off, his body dismembered and his trunk thrown to the dogs as an example to would-be traitors. It was also a lesson to others not to show clemency to a defeated king.

Henry reigned for another five years. Nevertheless, the principle of regular parliaments containing barons, knights and citizens was maintained.

However, there was a matter of greater importance for Henry: the reconstruction of Westminster Abbey. That building is the main consequence of the failure of the attempts to kill the King at Lewes and Evesham.

of Provence

of Provence

EDWARD I Margaret===King Beatrice===Duke [see page 80] Queen of

Scotland Alexander III of

Scotland John II Lady===Edmund===Blanche Katherine

Artois

Margaret Queen of Norway

+

Alexander Prince of Scotland

David

Arthur

+

John

+

Marie

+

Pierre

+

Blanche +

Eleonore Thomas 2

nd

Earl of Lancaster +

Henry

3

rd

Earl of Lancaster +

John

+

Mary

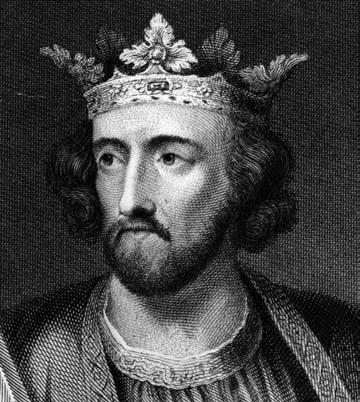

EDWARD I

16 November 1272 – 7 July 1307

After the victory of the royal army at Evesham, followed by the killing of the surviving Montfortian soldiers, peace reigned in England.

With Edward’s record of slaughtering fleeing Londoners at Lewes and surrendering Montfortians at Evesham, it is no surprise that the papal legate invited Edward to take part in the Eighth Crusade. Edward set sail in 1270, taking 1,000 knights with him. He also took his wife, Eleanor of Castile. Edward and Eleanor had married in 1254, when he was fifteen and she was thirteen. She would bear him fifteen children.

By the time they arrived in Tunis, where King Louis IX of France had been trying to establish a Christian kingdom, Louis had died and the Eighth Crusade was over. So Edward journeyed on to the Holy Land to take part in what would be the Ninth Crusade. Shortly after landing, Edward’s knights joined the other crusading forces in attacking the town of Qaqun. Edward was denied the opportunity of further killing when, despite his objections, a truce was agreed.

The crusaders then moved on to relieve Acre from a siege led by the Sultan of Egypt. Next, Edward took Nazareth, after which he had all its inhabitants (Muslims, Jews and even some Christians) massacred. As the armies prepared for further slaughter, one of the emirs sent a representative to discuss terms with Edward. When the negotiator arrived, he was quickly ushered into Edward’s room.

It was a trick, this man was a member of the secret order of Nazaris. They were a sect of the Ismailis, themselves a splitoff from the Shiite Muslims. Their creed required them to kill those whom they regarded as their enemies.

The founder of the order, Hasan bin Sabah, taught his followers that anyone who did not believe as he did was a legitimate target for murder. He lived in what is now Iran, and he demanded total obedience, recruiting impressionable young men, and indoctrinating them until they became fanatics. They were then schooled in deception so that they could infiltrate the lands of their enemies and live there quietly without revealing their true purpose. Trained to kill, they operated not by open warfare, but by murdering the leaders of their enemies, usually with a dagger and preferably in public. That meant that the murderer was invariably apprehended and executed. It was actually the desired result, as Hasan bin Sabah had promised the killer that he would be a martyr and would go to Paradise to be rewarded with 72 virgins.

People believed that these young men must have been drugged with hashish to carry out such missions. For that reason they became known as ‘Hashishim’, which in time was corrupted to ‘Assassin’ – a word later adopted in many languages for the killers of prominent people.

Suddenly the Assassin drew a large dagger from within his robe and leapt forward. Edward was unprepared for the attack; nevertheless he managed to turn to the side, and he was stabbed in the arm. However, Edward was a formidable adversary, so tall that his nickname was ‘Longshanks’. The injured Edward kicked out at his assailant and then picked up a stool with which he hit his would-be murderer, knocking him to the floor. Now Edward leapt on top of the man, and they grappled fiercely until Edward managed to wrench the dagger from the Assassin’s hand, although not before Edward had been slashed across the forehead.

Having heard the noise of the scuffling, armed men came running to Edward’s aid, and the Assassin was killed. Edward’s wounds were not of themselves life-threatening, but the dagger had been dipped in poison. After several days the wounds turned a dark colour, and there were fears that the poisoning would be fatal. Eleanor realised the danger and – so the doubtful story goes – she sucked out the poison. Then the skills of the court physician ensured Edward’s recovery. Now it was time to return to England.

Edward and the Assassin

Edward and the AssassinOn the journey home, news arrived that King Henry III had died and that as the first son Edward had been proclaimed king, heredity now being the accepted test. As the fourth king named Edward, he was initially called Edward IV following Edward the Elder, Edward the Martyr and Edward the Confessor. Some time later it was decided that the numbering of English monarchs should start afresh after the Norman Conquest (supporting the dynasty’s claim that they founded the English nation), so Edward became known as King Edward,

then Edward I when his son was crowned Edward II.

Edward replenished his treasury by selling confiscated estates back to the barons who had sided with de Montfort. Suitably enriched, Edward’s first target was the Welsh. The selfappointed Prince of Wales, Llewellyn ap Gruffydd, refused to pay homage to Edward, so in 1277 Edward marched his army into Wales and defeated Llewellyn and his forces with great bloodshed. Five years later, Llewellyn and his brother, Dafydd, led a rebellion against English rule. Edward took his army back to Wales, and after some early reverses he crushed the Welsh, Llewellyn being killed and decapitated. Dafydd escaped, but he was eventually handed over, tortured and executed. Edward then built a series of castles across Wales to ensure the continued subjection of the Welsh and the incorporation of Wales into England.

Now it was time for the Scots. When King Alexander III of Scotlanddiedin1286by‘fallingoffacliffatnight’,hissuccessor was his granddaughter, Margaret of Norway (Alexander’s daughter had married the King of Norway). Edward insisted that Margaret marry his heir, Edward Prince of Wales, so that the crown of Scotland would be obtained by the Plantagenets. The plan failed when the seven-year-old Margaret died at sea while travelling from Norway to Scotland. Then the Scottish lords asked Edward to decide which of the several contenders for the crown should be their king. He selected John Balliol, who was a 3 x great-grandson of King David I of whom Alexander III was a 2 x great-grandson. Balliol went on to rule Scotland as Edward’s puppet.

With the Welsh and the Scots suppressed, Edward turned on the Jews. They had served a useful purpose by raising money for the crown and for the citizens, mainly through their foreign contacts. As such, they were treated as chattels of the King and were entitled to his protection. However, Edward was now able to borrow money from the Lombards and Florentines, so he banned the Jews from moneylending and most other trades, and ordered them to wear a yellow badge. It was not enough, so he had 600 Jews imprisoned in the Tower and held for ransom. On payment of the ransom, 300 of the Jews were hanged and many more were dragged from their homes and killed.

The murder of the Jews enabled whatever they had left of value to be seized by the Crown, as Jews belonged to the King and consequently so did their assets when they died. Now that they were destitute, the Jews were no longer a source of tax revenue. In 1290 by the Edict of Expulsion, Edward confiscated their remaining property and expelled the surviving Jews from England. Many were thrown overboard by sailors on the voyage to France. The Edict also provided that no Jews could return to England, and any who were found were to be decapitated.

Borrowing from Lombards and Florentines would bring problems. When it was time to repay, as Christians they could not be murdered so easily. Also, they had a country to return to, so taxation of moneylenders had to be limited.

It was also in 1290 that Queen Eleanor died. Three years later, Edward decided to marry Blanche, the half-sister of King Philip IV of France. Philip agreed, provided Gascony was handed over. As Edward waited for his bride, Blanche was dispatched to marry the son of King Albert I of Habsburg, the founder of the dynasty. Philip told Edward that it was no problem, he could have Blanche’s sister, Marguerite, instead. But Marguerite was only 11 years old, and the 55-year-old Edward angrily rejected the proposal. So Philip seized Gascony, and Edward declared war.

With the war against France going badly, Edward again turned to the Scots. He humiliated Balliol by summoning him to Westminster, and the Scottish barons rebelled. Then Balliol renounced his fealty to Edward and made a treaty with the French. That was something Edward could not allow. In 1296 he marched into Scotland with his army, stopping en route to sack Berwick, killing all 11,000 inhabitants and razing the town to the ground. After defeat at Dunbar, Balliol was forced to abdicate and was imprisoned in the Tower until he was released into the custody of the Pope. Having lost their king, the Scottish barons surrendered.

That surrender did not end the spirit of resistance; a Scottish army led by William Wallace won a significant victory over the English at Stirling Bridge, and he followed up with a guerrilla campaign. In the end, Wallace was defeated at Falkirk. The Scots handed him over, and Edward had Wallace hanged, drawn and quartered.