Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe (11 page)

Read Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe Online

Authors: Ian Castle

Tags: #History, #Europe, #France, #Military, #World, #Reference, #Atlases & Maps, #Historical, #Travel, #Czech Republic, #General, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #19th Century, #Atlases, #HISTORY / Modern / 19th Century

Having taken the final decision to turn away from Britain, Napoleon’s army responded enthusiastically. They were not sailors and the thought of crossing the Channel in cramped unseaworthy vessels must have caused great consternation. But a campaign in Europe, marching on the Danube, was one they understood well.

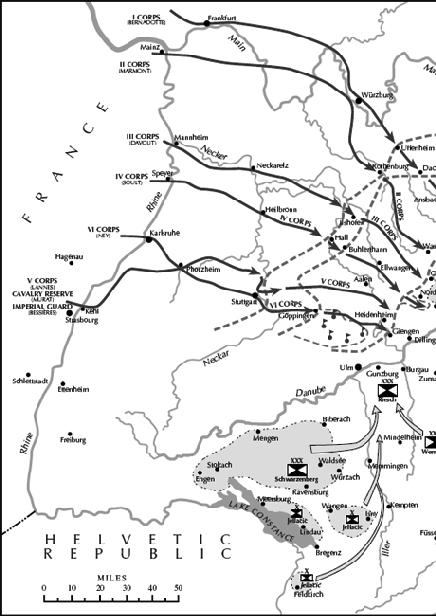

Three main routes provided the line of march to move the four corps from the Channel coast to the Rhine. Ney’s VI Corps marched from Etaples, via Arras, Laon, Reims, Vitray and Nancy to Hagenau. Lannes’ V Corps preceded Soult’s IV Corps from the Boulogne area via St Omar, Cambrai, Sedan and Metz, where the two corps diverged: Lannes heading for Strasbourg and Soult establishing himself at Speyer. Davout led the northernmost of the Channel corps from Ambleteuse via Lille, Namur, Luxembourg, and Sarrelouis to Mannheim. The leading divisions of each corps began marching on 28 or 29 August, with 48-hour intervals between each of the following divisions. The total marching distance of each corps varied between 350 and 380 miles, with Lannes’ corps due to arrive in Strasbourg by 23 September and the others in position two days later. With no danger from enemy attack, Napoleon could break up his corps into their component parts, and by moving them on three separate lines significantly increased their rate of progress. Also, he could call on the resources of France to provide food and shelter for the men as they progressed. To this end, staff officers rode ahead to make arrangements with the towns that would be required to provide succour for the army. But even for Napoleon things did not always go entirely to plan.

Due to the need for Napoleon to delay announcing the redirection of the army to the Rhine, it allowed only limited time to collect together the stockpiles of food and fuel required by the men. Requisitions for supplies often only arrived in towns shortly before the soldiers who needed them and little money was available to pay for them. Securing billets for the men also caused great difficulties. These were supposed to be found close to the road, but often the over-stretched civil authorities forced weary men to march an additional 4 or 5 miles at the beginning and end of the day to secure a roof over their heads. In Lille, the town refused to find quarters for Davout’s leading division, a

situation he immediately rectified by billeting his men on the inhabitants as though he were in an enemy’s country. His following divisions received a warmer welcome in the town. At Vitray, a division of Ney’s corps agreed to sleep in the empty barracks there if the town provided straw for the men to sleep on. This they did not do and when the officers complained to the mayor he refused to issue good conduct certificates which were required.

4

Due to the financial crisis in France it would appear that many French soldiers marched to war lacking certain items of kit: greatcoats in particular were in short supply, as were boots.

5

After the rigours of the march many units arrived barefoot on the Rhine. Horses suffered badly too, as there was little forage available for them, and both Davout and Soult had to cut back on guns or supporting wagons as losses mounted.

The lack of suitable transport forced the requisitioning of farm carts and wagons to convey essential supplies of infantry ammunition, but in these uncovered vehicles it is estimated that between 200,000 and 300,000 rounds were ruined by the weather and had to be abandoned before crossing the Rhine. Needless to say the owners of the carts, pressed into service, did not relish the thought of going to war and took any opportunity to desert, taking their horses with them. Soult reported that of the 1,200 transport horses he needed for his corps, he only secured 700, but he reported four days after crossing the Rhine that 300 of these had already deserted. Nevertheless, despite these handicaps, the four corps from the Channel coast arrived on the Rhine on schedule with 100,000 men. There, another 20,000 men of the Reserve Cavalry and 6,000 Garde Impériale, making their way from Paris, joined them.

Instructions for Marmont’s Corps in Holland did not leave Boulogne until 28 August and required him to march on 2 September from Zeist, near Utrecht, towards Mainz on the Rhine. Unable to secure enough transport horses, Marmont wasted no time and arranged instead to move his ammunition and heavy supplies up the Rhine by boat. Thus unencumbered, his corps marched some 230 miles by three roads to their destination via Nijmegen and Cologne. The whole of his corps arrived at Mainz over the 22–23 September. Then, after three days rest, they marched another 80 miles via Frankfurt to Würzburg, where the whole corps assembled on 1 October, having lost only nine men on the march.

Bernadotte, occupying Hanover with I Corps, received his orders on 1 September requiring him to march the following day. To maintain the desired level of secrecy, he was instructed to report that his command was returning to France and that Marmont was marching to relieve him. Proceeding first to the fortified city of Hameln, he stockpiled supplies for three months, placed all the artillery he captured during his occupation and left behind as garrison those of his men lacking fitness for the campaign ahead. Then he marched for Göttingen, where he assembled his corps prior to an advance towards Frankfurt. To speed his progress, Bernadotte opened negotiations with the

elector of Hesse-Cassel, whose territory lay across the most direct route. With permission secured, Bernadotte moved off but then received new orders redirecting him towards Würzburg and informing him he could not draw supplies from Frankfurt as they were reserved for Marmont. He arrived with his tired, hungry and exhausted men in Würzburg on 27 September, only to find that supplies supposed to be waiting for him had not yet arrived.

The arrival of Marmont and Bernadotte at Würzburg by the end of September added another 35,000 to the growing French force deployed along the Rhine and Main rivers. This increased further when Bernadotte received instructions to take command of the 23,000 men of the Bavarian army too. In a month Napoleon had gathered a force of about 184,000 men, extended in a great arc stretching for almost 200 miles from Strasbourg to the Bavarians’ position at Bamberg, all ready to descend on the Danube. Behind them a further 14,000 of Augereau’s VII Corps made steady progress across the breadth of France. Unaware of the strength of the storm gathering against him, Mack attentively watched the exits of the Black Forest for the emergence of the leading elements of the French army. He estimated they could muster no more than 70,000 men and remained confident that his army of 72,000 could hold them until the Russians arrived. But on 26 September, the day that Kaiser Francis left Landsberg to return to Vienna, Napoleon arrived at Strasbourg and his vast army began to cross the Rhine.

___________

*

Napoleon’s Proclamation to La Grande Armée, 30 September 1805.

Chapter 6

Refuge in Ulm

‘Ulm – the Queen of the Danube

and the Iller, the fortress of Tirol,

the key to one half of Germany.’

*

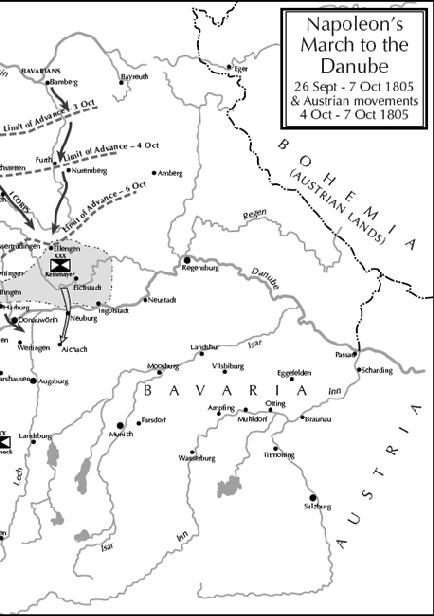

As La Grande Armée marched towards the Rivers Rhine and Main, Napoleon began to plan the second stage of the campaign. This plan, finalised on 10 September, required the army to cross the Rhine on 1 October, then swing down to the Danube, arriving along a 40-mile stretch of the river between Ulm and Donauwörth by 9 October. Three days later, on 13 September, Napoleon learned from the first of Murat’s reports that the Austrians had crossed the Inn. Then, on 18 September, he received a further report from Murat informing him that the Austrians had crossed the Lech and were pushing forward towards the Iller. This was a development Napoleon had not expected, but it presented him with a great opportunity. If he moved quickly and interposed his army between those of Austria and Russia, he had a chance to defeat his opponents separately before they could unite.

On 20 September he realigned his line of march further to the east, allowing more space in which to get behind the Austrians. With Donauwörth now selected as the central point of the advance, he directed the army against a 65mile stretch of the Danube between Günzburg, about 9 miles east of Ulm, and Ingolstadt. The French army commenced crossing the Rhine on 26 September. The Austrians’ rapid advance to the Iller made it clear to Napoleon that his opponents expected him to attack through the Black Forest. To maintain this impression for as long as possible, a feint was prepared through that difficult terrain. The longer he could hold the Austrians in this advanced position, the greater his chance of getting behind them.

One other important decision was made at this time too. On 17 September Napoleon received a communication from his aide in Berlin, Général de division

Duroc, who had been engaged in persuading Prussia to commit to an alliance with France. Duroc, fearing the failure of his mission, strongly recommended to the emperor that he should avoid sending Bernadotte’s command through the Prussian territory of Ansbach. Instead he advised that Bernadotte march via Würzburg and Bamburg, avoiding Ansbach completely. Duroc sensed that any violation of Prussian territory could bring the vacillating King Frederick William firmly down on the side of the coalition, crucially adding at least 150,000 men of the Prussian army to those of Austria and Russia. But Napoleon remained firm in his conviction. He recognised the danger posed by a belligerent Prussia, but also accurately concluded that any physical opposition would be slow to materialise. In the meantime, speed was of the utmost importance if he was to gain the advantage over the isolated Austrians in Bavaria. Accordingly, Bernadotte received orders to proceed through Ansbach. Other aides were despatched to Baden and Württemberg to win over support for the emperor’s cause, and gain approval for the advance of the army through these lands.

On 25 September Murat, now back on the Rhine after his exhausting spying mission, crossed the river at Kehl, near Strasbourg, with three dragoon divisions and a division of heavy cavalry, accompanied by Maréchal Lannes at the head of Oudinot’s Reserve Grenadier Division. These men were detailed to push through the Black Forest and occupy the attention of the Austrians.

Napoleon arrived in Strasbourg on 26 September. On arrival in the city, he was rapturously greeted by his army as they prepared to march. Cries of ‘Vive l’Empereur’ filled the air as the soldiers marched past, their hats decorated with sprigs of greenery; veteran and new recruit alike filled with enthusiasm for the task ahead. On the 27 and 28 September Napoleon despatched a number of letters in which he expressed his great wish that the Austrians would remain facing the Black Forest for another three or four days. He confided his view that: ‘If they will only allow me to gain a few marches on them, I hope to turn them and find myself with my entire army between the Lech and Isar.’

Murat’s cavalry, pushing through the Black Forest, soon encountered Austrian patrols, but the difficult terrain favoured the opposing light troops. Napoleon wanted prisoners from whom he could gain information to help unravel Austrian plans, but in this task his cavalry failed. The Austrians fell back as French columns threatened to overwhelm them, but although clouds of mounted men showed at the exits from the forest, they appeared reluctant to press on. In fact, having made a show of passing through the forest, only one dragoon division remained in front of the position. The rest of Murat’s cavalry and Oudinot’s grenadiers slipped away, back to the Rhine, to join the main advance.

Napoleon’s army pushed on from the Rhine as quickly as possible. By 1 October their right was at Stuttgart and the left at Neckarelz. Marmont and Bernadotte remained for the present at Würzburg and the Bavarians at

Bamberg. That same day, before he left Strasbourg with the Garde Impériale, Napoleon had one last meeting. Savary had returned from his spying mission to Bavaria and had grown in admiration for the special talents of his companion, the former smuggler Charles Schulmeister: talents that he felt could be exploited to the benefit of the French army. Schulmeister claimed to have friends in important positions in the Austrian army – in the field and in Vienna – and offered to infiltrate their headquarters as an agent of France. With Savary’s recommendation Napoleon agreed: Schulmeister was added to Savary’s pay roll and the following day the two men, spy master and master spy, set out for Stuttgart to finalise their plans.