Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe (25 page)

Read Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe Online

Authors: Ian Castle

Tags: #History, #Europe, #France, #Military, #World, #Reference, #Atlases & Maps, #Historical, #Travel, #Czech Republic, #General, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #19th Century, #Atlases, #HISTORY / Modern / 19th Century

Ney remained at Innsbruck while Deroy secured Kufstein, then on 11 November he ran into an Austrian rearguard, which delayed him further. Unable to wait any longer, Archduke John commenced his retreat towards the Drave, arriving at Klagenfurt on 20 November without the detachments under Jella i

i and Prince Rohan. Jella

and Prince Rohan. Jella i

i , in Vorarlberg since his march from Ulm, and unaware just how much things had changed since he left the city, had been unwilling to join John, as he felt he could still rejoin the army on the Danube. However, on 14 November Augereau surrounded him and forced his surrender, although much of his cavalry did escape and made it back to Bohemia. Prince Rohan was unable to reach the rendezvous but instead marched southwards and broke through into Italy with just under 4,000 men. He caused much concern until finally being cornered on 24 November at Castelfranco, 25 miles from Venice, by GD Gouvion St Cyr, at the head of a French force marching through Italy from Naples.

, in Vorarlberg since his march from Ulm, and unaware just how much things had changed since he left the city, had been unwilling to join John, as he felt he could still rejoin the army on the Danube. However, on 14 November Augereau surrounded him and forced his surrender, although much of his cavalry did escape and made it back to Bohemia. Prince Rohan was unable to reach the rendezvous but instead marched southwards and broke through into Italy with just under 4,000 men. He caused much concern until finally being cornered on 24 November at Castelfranco, 25 miles from Venice, by GD Gouvion St Cyr, at the head of a French force marching through Italy from Naples.

In the meantime, Maréchal Ney had failed to catch up with Archduke John. After reaching Klagenfurt, John rested for a couple of days before pushing on and was finally united with his brother, Archduke Charles, on 26 November at Marburg, still 150 miles south of Vienna. Charles now commanded a force of about 80,000 men, but learning that the French already occupied the capital he determined to retire into Hungary before striking north towards the main army congregating in Moravia.

Meanwhile, in Bohemia, Archduke Ferdinand continued to create a new formation at Pilsen. Then, having heard on 4 November of French troops at Linz, he advanced to a position roughly 60 miles to the north of them at Budweis, with just under 10,000 men. However, the rapid progress of the French army soon left him behind. On 14 November he received information that Kutuzov was retiring into Moravia after the battle at Dürnstein. He therefore began to march back towards Prague, about 130 miles to the north, before turning on the road towards Moravia, marching another 80 miles to Czaslau, where he arrived on 25 November. Here he established himself, 60 miles from the Moravian border.

Tsar Alexander was furious when he heard of the bloodless capture of the Tabor bridge. The Russian opinion of the Austrian army, already seriously damaged after Mack’s capitulation at Ulm, now took a further turn for the worse. Kaiser Francis, at Brünn, wrote: ‘I am full of consternation, this imprudent and inexcusable trick destroys the whole confidence of my Allies at a single stroke and interrupts our good harmony.’

13

But while tsar and kaiser raged, Kutuzov had no time to consider the moral rights and wrongs of the issue. Unless he moved fast his exhausted army was in very real danger of being surrounded and destroyed by the jubilant Grande Armée.

__________

*

Report of the Battle of Dürnstein, 22nd Bulletin of La Grande Armée, St Pölten, 13 November 1805.

Chapter 11

‘March! Destroy the Russian Army’

*

Napoleon entered Vienna with the Garde Impériale on 14 November, setting up his headquarters outside the city in the magnificent surroundings of the Schönbrunn Palace, the Habsburg’s summer residence. But he remained there only two days while awaiting news of Kutuzov’s army.

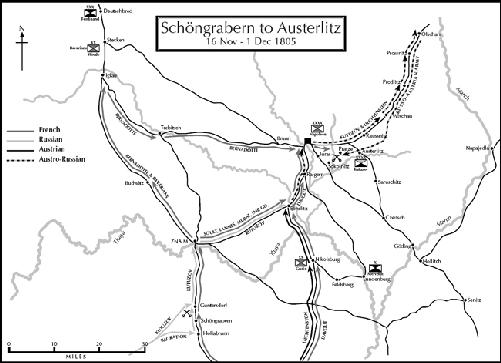

Having benefited from the unlikely capture of the Tabor bridge, Napoleon had no intention of failing to take advantage of this coup. Quickly formulating the next stage, he ordered Murat to lead a rapid advance from Vienna towards Znaim. Napoleon rightly believed this road must be Kutuzov’s new goal, for beyond Znaim the road led to Brünn and beyond that city marched Buxhöwden’s advancing army. After crossing the Danube on 13 November, Murat immediately pushed troops along the road to the north-west, two cavalry divisions advancing to Stockerau and Oudinot’s grenadiers reaching Korneuburg. The next day the rest of the Cavalry Reserve, V Corps and IV Corps also advanced on Stockerau, where they discovered a vast depot of supplies and military equipment of the Austrian army. Elsewhere, Napoleon ordered Davout to extend III Corps around Vienna to cover all the approach roads. Gudin’s division took up a position towards Neustadt, about 30 miles south of the city, from where he could offer support to Marmont, now in the Styrian Alps, watching for activity on the road to Italy. Friant’s division was east of the city, towards Pressburg, and Davout’s remaining infantry division (now commanded by Général de division Caffarelli, since the previous commander, Général de division Bisson, fell wounded at Lambach two weeks earlier), moved across the Danube to a position on the vast plain to the north of the city. Convinced that Kutuzov had no choice but to abandon his position at Krems, Napoleon ordered Bernadotte to march for the Danube and prepare a crossing close to the destroyed Krems bridge. Once across, Napoleon anticipated that Bernadotte’s rapid pursuit (I Corps and Wrede’s Bavarians) of the wily Russian from the west, would crush him against the other great pincer led by Murat from the south.

The Austrians, now commanded by Liechtenstein, fell back towards Brünn by a separate road, Murat detaching a dragoon division to follow their movements. While his command assembled at Stockerau during the day, Murat pushed patrols up the road towards Hollabrunn from where, in the early hours of 15 November, he received news of the presence of Russian troops approaching that town.

News of the capture of the Tabor bridge reached Kutuzov at Krems a few hours after the event. Instantly he abandoned his plans:

‘The forcing of the Vienna bridge by the enemy (an event which was not to be expected) and his march on Hollabrunn forced me to change my plans, and instead of defending the passage of the Danube and waiting patiently for support, I found myself obliged to march with all speed past Hollabrunn to avoid an unequal combat against infinitely superior forces and to follow my first plan of a junction with the army of the General Buxhöwden.’

1

In fact, Kutuzov now faced a race for survival. On the evening of 13 November Murat’s leading cavalry formations at Stockerau were only 15 miles from Hollabrunn on a good road. A quick glance at the map showed Kutuzov that if he was to escape he must push his tired men on a rapid march of some 25 miles, over poor tracks and paths, to reach that same town and access to the main road leading north. Fully aware of the difficulty of the situation, Kutuzov immediately gave the order for his army to prepare to march. Speed was now of the utmost importance. Reluctantly, therefore, he abandoned all the sick and wounded lying in the makeshift hospitals in Krems to the mercy of the French.

Pushing ahead, Kutuzov reached Ebersbrunn later that evening, 15 miles away to the north-east, where he established his headquarters. The rest of the army struggled in during the early hours of the following day. Fortunately for Kutuzov, while Murat needed the 14 November to assemble his full force at Stockerau, back on the Danube, Bernadotte was experiencing great difficulty collecting together boats and bridging materials for his river crossing. There was a glimmer of hope. As Kutuzov waited anxiously for his army, an Austrian officer advised him of a route which by-passed Hollabrunn and reached the Znaim road at Guntersdorf, nearly 9 miles north of the town. Denying his men any rest, Kutuzov drove them on right through the night of 14–15 November, constantly riding backward and forward, encouraging his ‘children’, as he liked to call his troops, and forever exhorting them to ‘Behave like Russians!’ But he also realised that this march alone was not enough to protect him from the French pursuit. Before leaving Ebersbrunn he called Bagration to him and explained the position. The only way to save the army was for a rearguard to make a strong defence at Hollabrunn and deny the road to the French while the

army made good its escape. General Maior Prince Peter Bagration, a descendant from an ancient dynasty of Georgian kings, had already proved his abilities in battle on many occasions during his twenty-three years’ military service. He was considered calm in a crisis and a brave, ferocious fighter. There could be no one better suited for the task.

Bagration received additional Russian troops to bolster his depleted command up to about 7,000 men, as well as Nostitz’ battered brigade: the only Austrian formation still fighting alongside the Russians. Then, diverging from the main army, Bagration headed across country to Hollabrunn on his daunting mission. Kutuzov momentarily let his feelings show and wept as they departed, convinced of the inevitable destruction of this meagre force, but he later wrote: ‘I would have nevertheless considered it satisfactory to sacrifice one corps for the sake of the army.’

2

Bagration assembled his forlorn hope at Hollabrunn at midday on 15 November, but was unable to discover a suitable defensive position. Leaving Nostitz covering the approaches to the town with the 4. Hessen-Homburg-Husaren and a number of Cossack detachments, he fell back 4 miles and established his force near the village of Schöngrabern. Within a very short time Murat’s advanced cavalry detachments arrived in sight of Nostitz, who drew back to this new position. Bagration feared an immediate attack, but it did not materialise.