B004R9Q09U EBOK (22 page)

Authors: Alex Wright

For all its exhaustive ambition, Wilkins’s scheme explicitly excluded many possible topics, including fictional and “complex” phenomena as well as place names, clothing, games, food, music, and, curiously, religious sects. He thought his language was best suited to describe simple, observable things and that more elusive concepts and ideas were best treated with “a more mixed and complicated signification.”

34

Nonetheless, Wilkins believed that the truth of God’s creation could be discovered primarily in observable nature, not through the received wisdom of the church. Elsewhere, he argued for the separation of scientific inquiry from religious doctrine, urging his contemporaries not to be “so superstitiously devoted to Antiquity as for to take up everything as canonical which drops from the pen of a

Father.”

35

Wilkins saw his life’s work as an endeavor to bring humanity closer to God by forsaking superstitious beliefs in favor of honest intellectual striving.

For a time it looked as though Wilkins’s ambitions might be realized. The book met with an enthusiastic public reception after its initial publication. The Royal Society began using the system to organize its collections, and copies of the book circulated throughout Europe. Wilkins himself hoped the

Essay

was only a beginning; for the language to reach its full realization, he thought, would require the efforts of “a College or an Age.” “I am not so vain,” he wrote, “as to think that I have here completely finished this great undertaking.” He hoped that the

Essay

would serve as an ontological beacon for future generations.

Wilkins would doubtless have been dismayed to discover that, centuries later, his life’s great work is now best remembered not as the birth of a universal language but as the butt of a literary joke. Today, Wilkins is largely known as the target of Jorge Luis Borges’s famous satire, “The Analytical Language of John Wilkins.” Taking stock of Wilkins’s system, Borges writes:

Having defined Wilkins’ procedure, we must examine a problem that is impossible or at least difficult to postpone: the value of the forty genera which are the basis of the language. Consider the eighth category, stones. Wilkins divides them into vulgar (flint, gravel, slate), middle-prized (marble, amber, coral), precious (pearl, opal), more transparent (amethyst, sapphire) and earthly concretions not dissolvible [

sic

] (pit-coal, oker and arsenic). Almost as surprising as the eighth, is the ninth category. This one reveals to us that metals can be imperfect (vermillion, mercury), factitious (bronze, brass), recrementitious (scoria, rust) and natural (gold, tin, copper). Whales belong to the sixteenth category; viviparous oblong fish.

36

Borges went on to mock Wilkins’s seemingly arbitrary classification with a modest taxonomic proposal of his own, masked as a fictional Chinese encyclopedia called

The Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge

. Here, he proposed a wildly orthogonal system for classifying animals as:

a. belonging to the Emperor

b. embalmed

c. trained

d. sloppy

e. sirens

f. fabulous

g. stray dogs

h. included in this classification

i. trembling like crazy

j. innumerable

k. drawn with a very fine camelhair brush

l. et cetera

m. just broke the vase

n. from a distance look like flies

Borges concluded that Wilkins’s system was doomed to fail because “it is clear that there is no classification of the Universe not being arbitrary and full of conjectures. The reason for this is very simple: we do not know what the universe is.” Much as Borges’s essay deserves its fame, we must ask whether it was perhaps a bit uncharitable to the unfortunate Mr. Wilkins. Wilkins never saw himself as any kind of absolutist; he railed against the arbitrary top-down hierarchies of the church and saw his system as, after a fashion, a bottomup endeavor. He was an empiricist, not an authoritarian. Paradoxically, Wilkins might even have appreciated Borges’s joke.

Barely a century after Camillo had wowed his Venetian audience with his gearbox Theater of Memory, Europe had witnessed a period of remarkable intellectual fermentation. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, the old scholastic arts of the monasteries had faded to oblivion, supplanted by a new secular ethic of scholarship. The authority of the church had eroded to make way for a new mode of intellectual self-reliance best exemplified in the emerging scientific method and the dawning Age of Reason. Meanwhile, the ongoing

caterwaul of publishing continued to fuel interest in a conceptual system capable of accommodating a growing tide of printed knowledge. The old wooden theaters, memory wheels, and artificial languages began to look like quaint relics of the bygone era of the monkish mind. While none of these systems would last, these pioneering efforts mattered less for what they actually accomplished than for the vision they suggested. These brilliant failed experiments in mnemo-technology pointed the way toward an even greater undertaking that would occupy philosophers for centuries to come: the quest for a universal classification.

With the emergence of the scientific method and the rise of Renaissance secular scholarship, seventeenth-century Europe witnessed a scholarly publishing boom. Across the growing university towns and printing centers of Europe, writers and printers turned out a growing volume of books on all kinds of topics: poetry, philosophy, politics, the arts and the natural sciences, as well as traditional religious and devotional texts. Before 1500, European printers produced about 15 million to 20 million books (from a total of 30,000 to 35,000 different titles); in the century that followed, that number mushroomed to nearly 200 million (from 150,000 to 200,000 titles).

1

As books flooded the market, the burgeoning quantity of available information created the conditions for a new kind of book to emerge: the encyclopedia.

Today we think of encyclopedias as dull reference works, secondary sources relegated to school libraries or bundled with our computers on CD-ROMs. In the seventeenth century, however, the encyclopedia represented a major innovation: a new literary technology that promised to help readers cope with a surging tide of new information. Encyclopedias did more than just give users an

easy reference source; this new technology also had revolutionary implications.

In 1624 the English playwright Thomas Heywood published an immensely popular book called the

Gunaikeion

, a proto-encyclopedia that purported to catalog all available information about his favorite subject: women. Inside this thick tome readers would find tales of brave queens, learned ladies, chaste damsels, Amazons, witches, and even a transgendered woman or two. Although Heywood’s name graced the cover, the

Gunaikeion

was a compilation of material culled from other popular books of the day, condensed, as Heywood put it, into “a small Manuell, containing all the pith and marrow of the greater.”

2

Like a kind of Renaissance hypertext, the book had no table of contents, no conceptual “top” or Aristotelian subject hierarchy.

Instead, it presented its contents in a loose structure that left the reader plenty of discretion in choosing how to navigate the text. In synthesizing a vast body of recorded knowledge on the subject of women, Heywood grappled with what literary scholars Crook and Rhodes call the “intractability of his subject matter.” Rather than try to shepherd his fair subjects into a fixed classification, Heywood instead hit on a novel scheme: “I have not introduced them in order, neither Alphabetically, nor according to custome or president; which I thus excuse: The most cunning and curious Musick, is that which is made out of discords.”

3

The term “discords” seems like a useful rubric for the problem of organizing a large collection of information drawn from many disparate sources. In our era of distributed information systems, information architects struggle with the problem of imposing a workable order on an expanding body of information drawn from remote sources. Heywood anticipated this question long before anyone started using terms like “hypertext,” articulating a system for organizing information that did not invoke a top-down hierarchical classification but emerged through a dialogue between author and readers—a kind of ad hoc network—working together to interpolate the contents of other books that had come before. As Heywood put it, his new book was “all mine and none mine. As a good hous-wife out of divers fleeces weaves one peece of Cloath, a Bee gathers Wax and

Hony out of many Flowers, and makes a new bundle of all … I have laboriously collected this Cento out of divers Writers.”

4

For example, when Heywood recounts the startling deeds of a woman who wrote an illustrated sex manual, he wonders whether she might best be classified a “poetess” or a “she-monster.” Similarly, when he tells of the great Queen Semiramis, a brave and noble woman of antiquity, he lets readers gauge whether she might best be tagged as a valorous queen, a murderess, a transvestite, or a practitioner of bestiality.

5

Writing of Queen Elizabeth, Heywood sings her praises in polymorphous terms:

Elizabeth, of late memory, Queene of England, she that was a Saba for her wisdome, an Harpalice for her magnanimitye … a Cleopatra for her bountie, a Camilla for her chastitie, an Amalasuntha for her temperance, a Zenobia for her learning and skill in language; of whose omniscience, pantarite, and goodnesse, all men heretofore have spoke too little.

6

That process of condensation led Heywood to grapple with questions of classification and values. For example, in considering possible approaches to classifying historical events, Heywood writes: “Of History there be foure species, either taken from place, as Geography; from time, as Chronologie; from Generation as Genealogie, or from gests (deeds) really done, which … may be called Annologie: The elements of which it consisteth are Person, place, time manner, instrument, matter and thing.”

7

Heywood seems to anticipate the kind of multidimensional classification that the great Indian librarian Ranganathan would propose centuries later in his famous Colon Classification (see

Chapter 9

and

Appendix D

).

Heywood’s attempts to liberate his text from fixed top-down categories, as Crook and Rhodes write, “throw into startling relief questions of classification and the logical disposition of knowledge in the period before the establishment of classical taxonomies from the late seventeenth through to the nineteenth centuries.” Heywood does more than just call those taxonomies into question. He seems to suggest a prescient alternative to top-down systems of knowledge: a world in which readers actively participate in structuring the uni

verse of available knowledge, rather than following a classification imposed from on High. “The digressiveness of both hypertext and the

Gunaikeion

represents a departure from the kind of narrow, linear thinking that we traditionally characterize as male,” write Crook and Rhodes, “and approximates more closely to ways of thinking and learning which in our present culture are considered by some to be the result of women’s socialization.”

8

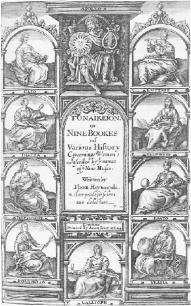

Cover plate of Heywood’s

Gunaikeion.

Reproduced by permission of the University of Edinburgh Library, Edinburgh, Scotland.

As one of the earliest examples of an encyclopedia-like volume, Heywood’s popular work proved there was a poplar market for such synthetic works. Over the next 200 years, scholars would find the notion of a meta-book drawn from the contents of other books increasingly alluring. Ultimately, this quest would lead to whole new ways of thinking about the structure of human knowledge and eventually to the great Victorian quest for a universal classification. Those efforts, as we will see in the pages that follow, would eventually find themselves bogged down with increasingly rigid hierarchical constructs; but in their earlier incarnations, encyclopedias seemed to offer the hope of a new, flexible, reader-driven experience. Heywood’s notion of a book whose structure is supplied at least in part by its readers, seems to foreshadow the self-organizing information ecosystem of the World Wide Web, which, like Heywood’s women, seems to resist categorization.