B004R9Q09U EBOK (20 page)

Authors: Alex Wright

So Camillo’s theater represented the culmination of an apostasy long in the making, the conflation of memorization with learning. With the decline of monasticism, however, it also represented an important effort to translate the previously secretive technique for a broader lay audience. And while the simplistic literalism of Camillo’s boxes and windows may have represented a debased version of the original art, it also marked a philosophical turning point at the beginning of the Renaissance. It represented, as Yates puts it, “a new Renaissance plan of the psyche, a change which has happened within memory, whence outward changes derived their impetus.” By giving the once-ethereal art a concrete form, Camillo transformed the old monastic art into a vehicle for secular aspiration. In so doing, he also anticipated the broader philosophical trajectory of the Renaissance. For the medieval monastics the art of memory was an antidote to the weakness of the human mind; by contrast, “Renaissance Hermetic man believes that he has divine powers; he can form a magic memory through which he grasps the world, reflecting the divine macrocosm in the microcosm of his divine

mens

.”

9

Camillo, it should be noted, never actually completed his theater. He died before he could finish raising the funds to complete his ambitious vision. Soon after Camillo died, the first generation of European humanists began to decry the old scholastic ways. Writers like Erasmus (Viglius’s friend) criticized the old medieval art, enjoining scholars to embrace a new rationalism that relied on more “natural” or linear forms of memory. Other influential European thinkers like Philipp Melanchthon, Cornelius Agrippa, and Michel de Montaigne all pilloried the monastic art of memory. Thomas Fuller bemoaned the “Memory-mountebanks” who had corrupted the classical art of memory by locking it in the cloister and keeping it from being used for practical purposes.

10

“For the Erasmian type of humanist the art of memory was dying out,” writes Yates, “killed by the printed book, unfashionable because of its mediaeval associations, a cumbrous art which modern educators are dropping.”

11

For the early modern humanists, the art of memory “belonged to the ages of barbarism; its methods in decay were an example of those cobwebs in monkish minds which new brooms must sweep away.”

12

As Europe entered into a new period of secular reason and scientific inquiry, the old art of memory would slowly fall into disrepute. At the end of the sixteenth century, however, it would see one more burst of popular interest, thanks in part to the high-profile heresies of Europe’s great intellectual maverick Giordano Bruno.

On February 9, 1600, Bruno bowed on one knee before the Grand Inquisitor, after 6 years in papal custody. The charge was heresy, and the Inquisition had pronounced him guilty. When the executioners presented Bruno with a cross at the moment of his death, he waved it away. He thought he had already found his salvation.

Born in 1548, Bruno had trained as a Dominican friar in Naples, where he had studied and mastered the art of memory. He eventually forsook the monastery for a wandering life that took him through France, England, and Germany. Along the way he began teaching the art to interested lay students, including no less a personage than King Henri III of France. Bruno would later recall that when the king summoned him to court, he first “asked whether the memory which I had and which I taught was a natural memory or obtained by magic art; I proved to him that it was not obtained by magic art but by science.”

13

In truth, however, Bruno’s version of the art contained a great deal of “magic.” Bruno saw the practice not just as a tool for strengthening the memory but as a transcendental gateway to “innumerable worlds.” He expanded the scope of the art beyond the usual doctrinaire topics of the monasteries, using it to integrate the classical wisdom of the Greeks, the magical religion of the Egyptians, ultimately penetrating, he believed, the highest truths of creation. In Bruno’s rendition the art joins the lower world of physical reality with the incorporeal essences of the celestial sphere, for “it is by one and the same ladder that nature descends to the production of things and the intellect ascends to the knowledge of them.”

14

In attempting to join heaven and earth, Bruno embraced an Aristotelian conceit: that the phenomena of the material world are expressions of inner essences, that things are, in a sense, symbols of themselves. It was, as Yates puts it, “a highly systematized magic.”

15

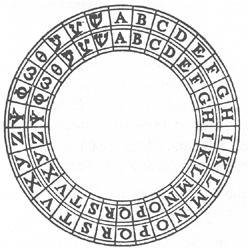

Bruno interpolated the old art into a new occult form of practice,

claiming to have unlocked the deepest mysteries of the phenomenal world thanks to a complex mnemonic device called the memory wheel. The memory wheel relied on a series of ostensibly magic numbers, especially 30

16

and 150, with 150 images broken out into five sets of 30 images each, all arranged in concentric circles, or wheels.

Memory wheel, from Giordano Bruno’s

De Umbris Idearum

, 1582.

In a meticulous feat of literary reverse-engineering, Yates managed to decipher Bruno’s dense text in sufficient detail to construct a working model of the memory wheel—a feat that, as far as we know, no one had attempted in 400 years. She describes how she believed the mnemonic device must have operated:

The lists of images given in the book are marked off in thirty divisions marked with these letters, each division having five subdivisions marked with the five vowels. These lists, each of 150 images, are therefore intended to be set out on the concentric revolving wheels. Which is what I have done on the plan, by writing out the lists of images on concentric wheels divided into thirty segments with five subdivisions in each. The result is the ancient Egyptian looking object, evidently highly magical, for the images on the central wheel are the images of the decans of the zodiac, images of the planets, images of the mansions of the moon, and images of the houses of the horoscope. The descriptions of these images are written out from Bruno’s text on the central wheel of the plan. This heavily inscribed central wheel is the astral power station, as it were, which works the whole system.

17

The system builds on wheel after concentric wheel, spinning out into innumerable combinations whose mastery demands extraordinary dedication and concentration. Bruno’s path calls to mind the tantric practices of Tibetan Buddhism, which similarly rely on intricate visualizations and extreme feats of memorization as pathways to spiritual liberation. Bruno’s “astral power station” was a prodigious piece of conceptual engineering, with its endless combinations of juxtaposed letters revealing layer upon layer of nested meaning. At the first level the wheel contains an inventory of empirical facts concerning the kingdoms of animals, vegetables, and minerals. Additional turnings of the wheel reveal new layers of abstraction, as the concentric circles expand to catalog the whole sweep of human achievement, encoding the names of mythical figures who represent the enabling technologies of civilization: Pyrodes, the inventor of fire; Aristeus, the discoverer of honey; Coraebus, the potter; and so on. The list then moves through more advanced technologies like glassblowing, surgery, writing (represented by our old Platonic friend Thoth), and up through the rarefied magical arts like necromancy, chiromancy, and pyromancy, and then to higher and higher degrees of celestial wisdom. It is a breathtakingly complete array of the known intellectual universe. And with a touch of authorial chutzpah, Bruno places himself squarely in his own cosmology, invoking himself as “Ior” (short for Iordano Bruno), the inventor of the “key.”

Whereas the medievalists of the Thomist tradition treated the art of memory as a remedy for the failings of the human mind, Bruno saw it as a fruitional path, a means to put people in touch with their innate divinity. “If you contemplate this attentively,” Bruno wrote, “you will be able to reach such a figurative art that it will help not only the memory but also all the powers of the soul in a wonderful manner.”

18

Like the Gnostics, Bruno thought he had found a path of liberation that relied purely on training the mind, rather than on pious obedience to the top-down dictates of the Church.

While Bruno based his memory technique on the art of memory that would soon fall into disfavor among Renaissance scholars, his particular use of the technique anticipated the scientific method. By using the technique to articulate a system for classifying information

about the natural and cosmological worlds and articulating the rules of that system in writing, he paved the way for the emergence of empirical methods that would soon transform Renaissance scholarship.

In Howard Bloom’s parlance, Bruno would qualify as a first-rate diversity generator, a fount of alternative hypotheses who failed to survive the intergroup tournament—the Inquisition—and ultimately perished at the hands of conformity enforcers—the Church (see

Chapter 1

) .

19

But despite Bruno’s unfortunate demise, his ideas found their way into the mainstream of Renaissance thought, paving the way for the advent of the scientific method.

Ultimately, Bruno’s practices amount to an aberration from the art of memory as it had been practiced beforehand. As historian Rhodri Lewis writes, “Bruno’s ambitions—if not his achievements—were at variance with the history of mnemotechnique.”

20

Throughout most of its history, the art of memory had been a practical tool for improving recollection; it was only in the latter years of the scholastic fascination that it began taking on mystical airs. After Bruno’s execution, the monastic practice of the art of memory faded almost entirely from public view, but traces of its impact would linger for centuries to come. An Englishman named Robert Fludd wrote about the practice in the seventeenth century. Some scholars have even speculated that the art of memory went back underground into esoteric occult circles, as it had during the Dark Ages. Yates believes that Bruno’s writings also embedded themselves into the secret practices of the Freemasons and Rosicrucians. Esoterica aside, however, the old medieval knowledge systems—with their cathedrals of imagery, theaters of memory, and books of mythological animals—were fast giving way to a new era of scientific reason. Soon, the old monkish ways would be all but forgotten, thanks in no small part to an Englishman well versed in the art of memory: Francis Bacon.

The most striking feature of Francis Bacon’s house in Gorhambury, England, was a lattice of stained glass windows, “every pane with severall [

sic

] figures of beast, bird and flower.”

21

Bacon, who had stud

ied the old art of memory in his youth, had taken great pains to create a physical facsimile of the old scholastic art in his house. Perhaps we can envision him gazing out his multicolored window, imagining the memory palaces he had visited in his monastic youth.

By the time Elizabeth I ascended to the throne in 1558, English intellectuals had started abandoning the mystery cults of the scholastics. The Cambridge-educated Bacon ultimately came to deride the old scholastic methods as overly stylized exercises in meaningless abstraction. His years in the monastery had given him a first-hand perspective on the futility of esoteric debates that seemed removed from practical problems: the medieval equivalent of the ivory tower syndrome. Along with Erasmus and other early humanist writers, he condemned the art of memory—in which he himself had trained—as a superfluous exercise that paled in comparison to an empirical style of reasoning based on direct observation and logical reasoning. “[W]e are certain that there may be had both better Precepts for the confirming and increasing

Memory

, than that Art comprehendeth,” he wrote, “and a better Practice of that Art may be set downe than that which is receiv’d.” He wrote of the art of memory, “it seemeth to me that there are better practices of that art than those received,” deriding the monastic tendency to celebrate their elaborate memory feats as “points of ostentation.”

22

He further derided the practitioners of the monastic art as a kind of intellectual gymnasticism practiced by “Tumblers; Buffones, & Iug[g]lers.”

Despite his condemnation of the monastic art of memory, Bacon did not reject the technique altogether, but yearned for a “better Practice of that Art,” stripped of scholastic excess. In his landmark

Novum Organon

(“New Tool of Reason”), he recommended the use of “artificial places in memory, which can either be places in the literal sense … or familiar or famous persons, or whatever you like (provided that they are organized properly).”

23

Bacon longed for a new intellectual philosophy that rejected the cloistered model of scholastic learning in favor of practical inquiry into real-world problems. While he rejected the idle contemplations of the monastics, he nonetheless recognized the value of mnemonic techniques as a bridge toward a new way of understanding the natural world.