B004R9Q09U EBOK (24 page)

Authors: Alex Wright

In the centuries that followed, scientists have expanded Linnaeus’s framework to include as many as 17 levels of hierarchical descriptors, notably adding the phylum (a division between kingdoms and classes) and additional subcategories. But in its original incarnation, the Linnaean system bore a striking resemblance to the folk taxonomies (see

Chapter 2

) that preceded it. This was no accident. While

traditional histories of science tend to give Linnaeus credit as the author of his system, in fact he drew on earlier folk traditions. What sets his system apart was his willingness to embrace folk conventions rather than try to assert his own idiosyncratic vision. Linnaeus intuitively recognized the wisdom of crowds. The subsequent success of his system stems from its roots in our evolutionary heritage. The du

rability of Linnaean taxonomy may have a great deal to do with the epigenetic rules governing folk taxonomy: hierarchical categorization of five to six levels deep, binomial naming conventions, and a “real name” or psychologically primary category. The genius of Linnaeus’s system owes not just to its transparency, but to its intuitive resonance with the epigenetic rules governing folk taxonomies. For many naturalists the Linnaean system simply feels “right.”

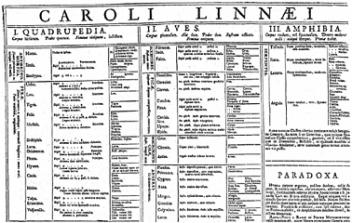

Section of the table of the Animal Kingdom from Carolus Linnaeus’s first edition of

Systema Naturae

(1735)

.

Linnaeus’s Classification

Level | Example |

Kingdom | Animals |

Class | Mammals |

Order | Primates |

Family | Hominidae |

Genus | Homo |

Species | Homo sapiens |

Whereas earlier schemes had stalled at two or three levels of hierarchy, Linnaeus seems to have hit on the precise structure of taxa that occurs among tribal societies. This should come as no surprise; Linnaeus drew heavily on these systems that had persisted through oral transmission since ancient times. Aristotle’s naturalist works were already widely known, providing a foundational work for naming conventions (the standard binomial convention of genus-species derives from Aristotle), but his Great Chain of Being provided only a one-dimensional hierarchy; it did not provide a unifying theoretical system. Meanwhile, the old folk taxonomies had always persisted in local communities, but while they shared a rough conformity, they were also highly heterogeneous.

Linnaeus’s system succeeded by incorporating aspects of folk taxonomies and Aristotelian classification and by articulating an easily understood system that relied not on the mental prowess of individual researchers but on a precise rule set. This rule set in turn lent itself to systematization and to a division of scientific labor. The hierarchical information system enabled an organizational hierarchy to take shape around it. Linnaeus created a team of researchers or, as he called them, “apostles,” to work under his guidance in fleshing out his classification; each apostle worked to complete a particular piece of the taxonomic puzzle.

By providing a rule set that other scientists could follow, Linnaeus paved the way for modern biology. Linnaeus himself allowed that his system was “artificial,” using as it did an arbitrary construct of Linnaeus’s own devising—the classification of plants according to “male” and “female” characteristics. Linnaeus even used the terms “husband” and “wife,” invoking a matrimonial metaphor that echoes

social kinship relations.

3

In fact, Linnaeus hoped someday to supplant his own system with a more “natural” classification that more accurately revealed God’s order and spent most of the rest of his career pursuing that elusive goal.

Today, Linnaeus ranks as the uncontested historical founder of modern biological classification. But his ascendance did not come easily. Linnaeus had a powerful rival on the scientific world stage: the French Comte de Buffon, the man who inspired Jefferson to send for his moose.

George-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, was, like Linnaeus, a botanist who had also worked as a royal gardener. And like Linnaeus he became fascinated with classifying flora and fauna. But unlike Linnaeus, Buffon eschewed strict hierarchies in favor of seeking a “natural” system more reflective of God’s will.

From 1749 to 1788, Buffon published his monumental

Histoire naturelle

, a compilation of information about known species. The work was a best-seller by eighteenth-century standards. Issued in 44 volumes (eight of which were published posthumously), the work became a standard text in European intellectual circles. Inspired by Pliny, author of the 37-volume encyclopedia of the natural world, Buffon rejected earlier Renaissance humanist attempts at reconciling Holy Scripture with observations about the natural world. Instead, Buffon proposed a strictly secular framework predicated on the deist view that God was more of a primal architect who set natural processes in motion, rather than the “hands-on” creator of each individual being.

Buffon believed that humans’ propensity for classifying the natural world stemmed from the inherent inadequacy of human perception. In his view the world existed more as a continuum of life forms; fixed categories were simply the insecure projections of feeble human minds. Buffon had little use for Linnaeus’s detailed classification system. He dismissed the work as an uninspired collection of tables.

Buffon’s opposition to the Linnaean system of classification, which was based on a narrow set of “essential” anatomical features, would lead him to develop an alternative system. He considered schemes that would take into account an animal’s physiology, ecology, functional anatomy (e.g., flying vs. swimming), behavior and geography. This approach ultimately proved unwieldy, but it did make him sensitive to patterns often ignored by Linnaean taxonomists.

4

It is not easy to see today who was the more “modern” of the two. While Linnaeus believed in the fixity of species, Buffon was convinced that species were constantly changing; he regarded Linnaean classification as too confining and arbitrary to reflect the true state of the natural world. In this sense, Buffon’s approach directly presaged Darwin; indeed, Darwin would later acknowledge his debt to Buffon.

In the eighteenth century, Buffon’s ideas seemed radically new. While Linnaeus believed that animal species reflected ideal forms that allowed for limited variation that did not change over time, Buffon believed that animals did indeed change in response to their environment, although each animal came preprogrammed with a

moule intérieur

(interior mold) that shaped their development. Since he believed that the natural world was constantly changing, Buffon saw that “artificial” classification systems like Linnaeus’s failed to allow for this variation. Buffon found the Linnaean system overly constraining, and thought that deriving classification from the characteristics of sexual organisms seemed too one-dimensional, failing to account for the richness and variety of nature. Instead, Buffon wanted to classify animals by their “communities of origin.”

Buffon was, in other words, an opponent of hierarchical systems. He approached classification from the bottom up, assigning classifications based on empirical observation rather than top-down categories. Most importantly, he believed that these classifications could change over time.

The scholarly rivalry between Linnaeus and Buffon spilled over into personal animosity. Linnaeus chose to name a particularly foulsmelling plant

Buffonia

. While history has relegated Buffon’s theory largely to obscurity, in its day the system commanded an influential following among Europe’s learned classes. The struggle between

Buffon’s and Linnaeus’s classifications swirled as one of that age’s most active public debates.

Buffon’s theory held one important corollary: that because species changed over time, they could also “degenerate” under adverse conditions. The discovery of such degenerate species would mark a resounding affirmation of his theory. Buffon believed he had found just such evidence in the form of the strange specimens coming back from the New World. In the

Histoire

, he wrote:

In America, therefore, animated Nature is weaker, less active, and more circumscribed in the variety of her productions; for we perceive, from the enumeration of the American animals, that the numbers of species is not only fewer, but that, in general, all the animals are much smaller than those of the Old Continent. No American animal can be compared with the elephant, the rhinoceros, the hippopotamus, the dromedary, the camelopard [giraffe], the buffalo, the lion, the tiger, &c.

5

Further, he noted that the New World appeared to have fewer species altogether—additional proof of that continent’s intrinsic inferiority. Given the paucity of species and the apparent deteriorated state of existing specimens, the New World was therefore (his theory went) an intrinsically “degenerate” place.

Which brings us back to Jefferson’s moose. As the recently appointed ambassador to France, Jefferson served as booster in chief for the young republic among the Parisian diplomatic set. He squarely faced the challenge Buffon had thrown down. Buffon’s doctrine of American degeneracy undercut the young country’s international standing. It was, Jefferson wrote, “within one step” of predicting that European immigrants would also degenerate in the New World. If true, what self-respecting European would consider picking up and relocating to such a place?

Jefferson had an especially keen fascination with the natural world. He had personally cataloged all the known plant species in the New World, compiled the 101 species of Virginia birds, filled his home in Monticello with an enormous collection of animal skulls and plant seeds, and kept exacting records of natural events around his home:

wind, temperatures, and 50 years’ worth of data on the annual springtime appearance of bugs and birds. Indeed, Jefferson was one of the primary contributors to the incoming flow of naturalist reports from the New World. His personal correspondence is peppered with disquisitions on naturalist topics ranging from philosophies of taxonomy to the genitalia of the mole.

In his

Notes on the State of Virginia

, Jefferson went to great lengths to disprove Buffon’s contention that American animals were smaller (and therefore inferior) to their European counterparts. Jefferson castigated Buffon’s theory of classification as a “no-system.” He castigated Buffon as “the great advocate of individualism in opposition to classification. He would carry us back to the days and to the confusion of Aristotle and Pliny, give up the improvements of twenty centuries, and co-operate with the neologists in rendering the science of one generation useless to the next by perpetual changes of its language.”

6

Jefferson embraced the Linnaean classification system, which he felt “offered the three great desiderata: First, of aiding the memory to retain a knowledge of the productions of nature. Secondly, of rallying all to the same names for the same objects, so that they could communicate understandingly on them. And Thirdly, of enabling them, when a subject was first presented, to trace it by its character up to the conventional name by which it was agreed to be called.” While Jefferson did not assert the Linnaean system to be intrinsically more accurate or true than other possible systems, he felt that its legitimacy derived largely from the sheer weight of its popularity.

I adhere to the Linnean because it is sufficient as a ground-work, admits of supplementary insertions as new productions are discovered, and mainly because it has got into so general use that it will not be easy to displace it, and still less to find another which shall have the same singular fortune of obtaining the general consent. During the attempt we shall become unintelligible to one another, and science will be really retarded by efforts to advance it made by its most favorite sons. … And the higher the character of the authors … and the more excellent what they offer, the greater the danger of producing schism.

7

Jefferson’s argument came in the corpse of that moose. It stood at least a third taller than its continental cousin. This was clearly no “degenerate.” It was a tangible refutation of Buffon’s theory of American degeneracy and an implicit endorsement of Linnaean classification. Jefferson presented the moose to Buffon personally, along with a copy of his

Notes on the State of Virginia,

in which Jefferson demonstrated that domesticated animals were consistently larger in America than in Europe, and made a compelling case for biodiversity by demonstrating that America harbored four times more species of quadrupeds than Europe. Buffon was sufficiently impressed with Jefferson’s argument that he promised to revise his theories. Unfortunately, Buffon died before completing the task.