Blood-Dark Track (20 page)

Authors: Joseph O'Neill

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Literary

O

n 3 February 1942, around the time my grandfather was making his fateful visa application to the British consulate in Mersin, Sir Patrick Coghill, the SIME agent based in Adana, visited Beirut. The baronet learned, to his ‘stupefaction and horror,’ that he had been appointed head of the British Security Mission in Syria. The BSM had been founded by Arthur Giles, the head of CID Palestine Police, and had accompanied the invasion force into Vichy-controlled Syria in the summer of 1941 with a view to assuming the counter-espionage activities of the Vichy Sûreté. In the event, the Sûreté records were destroyed before the British could get their hands on them. Coghill noted that, at the time, the loss of the records ‘was a bitter disappointment – but looking back I wonder whether we were not better off without them. As practically all the French agents and informers were Lebanese Christians, all their reports were hopelessly biased and distorted – yet if we had taken them over we would certainly have believed them and relied on them.’ At any rate, it soon became apparent that the Axis had no significant espionage capability in Beirut or elsewhere in the region. Little trouble was experienced from its agents, which, Coghill speculated, was perhaps due to the large number of ‘suspects and known pro-Axis sympathizers’ held in ‘internment camps for Enemy Aliens and Agents and Suspects’.

The administration of the camps – indeed, practically all internal administrative power in Syria – was in Free French hands. Nonetheless, when Sir Patrick Coghill assumed command of the British Security Mission in the summer of 1942, he was from that time on responsible for the continued detention of Joseph Dakak. Not surprisingly, there was no mention of my grandfather in Coghill’s autobiographical papers, which I read in an Oxford library. There was, however, another omission which did strike me as a little curious. Although he referred frequently to his life and home in Castletownshend, West Cork, and to his family, Sir Patrick Coghill made no reference to his uncle, who also lived in the village of Castletownshend, Admiral Somerville.

4

There are crimes of passion and crimes of logic.

– Albert Camus,

The Rebel

S

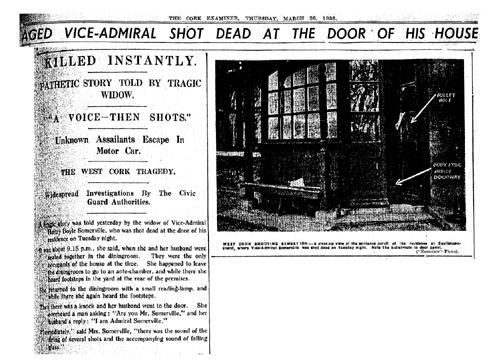

hortly after nine o’clock on the evening of Tuesday 24 March 1936, the occupants of The Point, Castletownshend, County Cork – Vice-Admiral Henry Boyle Townshend Somerville and his wife – heard footsteps on the gravel path outside their dining room window. Mrs Somerville said to her husband, ‘Perhaps that’s one of the boys coming to see you’ – the boys, in this case, being the young men of the locality who dropped by to ask the Admiral’s help in joining the British navy. ‘I’ll go and see,’ the Admiral said. He rose to his feet to receive the visitors personally: the cook and the housemaid were out for the evening at a play presented in the village by a travelling company. There was a knocking at the door. Admiral Somerville picked up an oil lamp, crossed the hall, and stepped into the porch at the entrance to the house. Mrs Somerville, who remained in the dining room, heard an indistinct voice outside the glass-panelled front door: ‘Are you Mr Somerville?’ ‘I am Admiral Somerville,’ Somerville replied correctly. Mrs Somerville heard gunshots and the sound of glass shattering. She grabbed a lamp

and rushed into the hall. As she entered, a strong gust of wind blew in through the open door of the porch, extinguishing the flame she carried. Mrs Somerville found herself in complete darkness. She called her husband’s name – ‘Boyle! Boyle!’ – but received no response. All that was audible was the sound of footsteps – the steps of two persons, was her impression – retreating down the gravel avenue towards the gate of the house. Mrs Somerville advanced in the darkness towards the porch. She saw her husband lying motionless by the doorway among the broken remains of his lamp.

Alongside the body was a piece of cardboard on which letters cut from newspapers had been glued. The message read, ‘This British agent has sent 52 boys to the British Army in the last few months.’

By order of Chief Superintendent McCarthy, the Corkman initially in charge of the investigation, the body was left untouched until the arrival from Dublin, on Thursday, of Chief Superintendent Woods of the Special Crimes Department, and Chief Superintendent Sheridan, Head of the Technical Bureau of the Civic Guards. Friday saw the arrival of Commandant Stapleton, the Free State army’s ballistics expert, and Dr John McGrath, the State Pathologist, who carried out a post-mortem examination.

At the inquest held later that day in the Somerville home, Dr McGrath gave evidence that the body was that of an elderly man, 5 feet 11 inches in height, dressed in a dinner suit and a bloodstained white dress shirt. On examination, the pathologist found six wounds. The first was a bullet wound in the left groin at the level of the pubis. The direction of the wound was from the left of the deceased towards the right, and downwards. The bullet was extracted from muscles in the right thigh, having travelled through the belly cavity, puncturing the intestine twice, and through the pubic bone. The second wound was situated at the crest of the ilium on the left side. This wound also tracked in a downwards direction. Dr McGrath found the bullet in the muscles on the right side of the small of the back. Wound number three was in the chest, situated 1½ inches to the left of the midline and 2¾ inches above the nipple line. This wound went partly through the breastbone, then through the membranes that covered the heart, then it punctured the left artery of the

heart at a point above the heart. Then the track went under the lining and through the back of the chest wall between the third and fourth ribs; it continued through the muscles of the back and the shoulder-blade bone, and terminated in the muscles at the back of the shoulder-blade, where a bullet was lodged. The fourth and fifth wounds (an entrance wound and an exit wound on the left upper arm caused by a bullet passing through and breaking the bone) were the only horizontal wounds. The sixth wound was at the angle of the lower jaw, an inch in front and below the left earlobe. The track of this wound was through the jawbone, which was broken, then downwards and rightwards and through the front of the spine, and through the tissues of the neck and the right shoulder blade, and finally into the muscles on the right side of the spine. Here another bullet was found. In total, at least five shots were fired.

The State Solicitor, a Mr T. Healy, addressed the inquest jury at length. He described Admiral Somerville as ‘the descendant of a proud family, the descendant of people who won distinction at home and abroad, the descendant of one of our incorruptible band who had fought to keep in this country a Parliament which had legislated for the entire country, the descendant of one who had disdained rank and wealth in order to fight for that Parliament which legislated for 32 counties and not for a dismembered and partitioned country.’ This was a reference to a great-grandfather of the deceased, Charles Kendal Bushe (1767–1843), the Lord Chief Justice of Ireland from 1822 to 1842, who in January 1800 spoke in the Dublin parliament against its forthcoming union with the English parliament. People also noted that the Admiral’s father, Tom Somerville, had been a friend of a local republican hero, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa (1831–1915). O’Donovan Rossa died in New York, and it was on the occasion of the repatriation of his remains, at Glasnevin Cemetery, that the republican Patrick Pearse famously proclaimed, ‘Life springs from death; and from the graves of patriot men and women spring living nations … [T]he fools, the fools, the fools! They have left us our Fenian dead, and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace.’

The deceased, Mr Healy continued, was a man who ‘had acted as

a kindly gentleman to all, and everybody who came to him for help and aid was assisted by him’. The suggestion that he was a recruiting agent for the British armed forces was, Healy stated, false. ‘Admiral Somerville never asked, sought or induced any person to join that army or navy, but when people came to him and asked him for a recommendation he gave it freely in so far as it lay in his power where he knew people, and when he did not know them he told them the procedure to be adopted. But he used no influence to get any man or boy into the English navy. Now, if every person who had signed a recommendation for boys to join the English navy is to be shot, I am afraid there will be a great number of people in this country who will be shot, because men in all stages and positions, clergy, have signed such recommendations. Surely, the least that might have been given to the deceased was a warning that his action was distasteful, and was regarded as unworthy of the conduct of Irishmen. No notice or warning was given to the deceased, but instead he was hurled to his death. No stain will lie on the memory of the deceased where he was known, and throughout the country the action which has taken place is abhorrent, and I again repeat that every effort will be made to trace the authors of it, though goodness knows, with modern means of communication, the assassin has the advantage on his side.’

The State Solicitor’s gloomy remark was directed at the fact that the killers had fled in a car that two schoolgirls had seen driving away from the house at great speed. It was not until the following day that guards arrived. A minute investigation began. Castings were taken of the tyre-marks left by the car, photographs and measurements were taken of the scene, fingerprints and footprints were thoroughly examined. A week after the homicide, forensic searches were still being carried out at Point House.

While the detectives went about their work, more details began to emerge in the press about the late Admiral. He was born in Castletownshend in 1863, the son of Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Henry Somerville (who served as High Sheriff of Cork in 1888) and Adelaide, daughter of Admiral Sir Josiah Coghill, Bt. Ships on which the Admiral served included the HMS

Shandon

, the

Agincourt

, the

Audacious

, the

Heroine

, the

Sphinx

and the HMS

Sealark

. He had seen active service in the Chilean–Peruvian war and the first Egyptian war, and as a hydrographic surveyor had sailed in waters by China and Ceylon and in the western and eastern Pacific Ocean. During the Great War he had commanded the

Victorian

,

Argonaut

,

Amphitrite

and

King Alfred

. He was awarded the CMG and made an officer of the

Légion d’Honneur

. After his retirement from the navy in 1919, the Admiral was employed by the Hydrographic Department at the British Admiralty. He wrote several books, including dictionaries of languages spoken in New Hebrides and New Georgia, Solomon Islands. Writing ran in the family: Edith Somerville, co-author of the Somerville and Ross books, was his sister. Boyle – the Christian name he went by – Somerville was a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Society and a Vice-President of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society. He was a charitable man and frequently contributed to the funds of the Skibbereen Conference of the (Catholic) St Vincent de Paul Society.

And indeed the assassination outraged the Catholic Church. In an address that was read out in every parish in his diocese, the Bishop of Ross stated that in respect of the crime there was ‘no single circumstance to palliate guilt in the slightest. It was not the result of sudden and overwhelming passion, an outbreak of uncontrollable excitement, momentarily taking away the full use of reason. No. It was a well-planned, carefully thought out and deliberately organized crime, with every move coolly forecasted and every precaution taken to ensure the subsequent safety of the perpetrator. It bore every mark of the crime of the coward, who will strike only when assured of impunity.… It is to be hoped,’ the bishop said, ‘that this awful crime will be a warning to our young men, who may be tempted to join Secret Societies, so often and deservedly condemned by the Catholic Church.’

Condemnation also came from the political establishment. In the Dáil, a government spokesman sympathized with the relations of the victim of ‘this cowardly crime’, and Cork County Council also passed a resolution expressing its sympathies. Councillor D. O’Callaghan said that the Admiral, whom he’d known for fifty

years, never did anything in his life that either Catholic or Protestant could be ashamed of. He was an idol of the people. He was not a recruiting agent for the British. Mr O’Callaghan himself had recommended persons to British armed forces for the last twenty to thirty years, poor men who came home with a pension of £300 and £400 to support their families. Senator Fitzgerald, speaking on behalf of Fianna Fáil, stated that even if the Somerville family differed from the rest of the country with respect to the national outlook, there must be room in this country for all shades and classes of opinion. (Hear, hear.) Mr O’Mahony, who wished to be associated with the vote, said that the Somerville family had, in the past, suffered for its convictions as far as Irish nationalism was concerned. Mr O’Mahony did not agree with the Admiral politically, but it was a terrible thing that he had received no warning.