Bloody Times (2 page)

Authors: James L. Swanson

Jefferson Davis walked from St. Paul’s to his office. He summoned the leaders of his government to meet with him there at once. Davis explained to his

cabinet

that the fall of Richmond would not mean the death of the Confederate States of America. He would not stay behind to surrender the capital. If Richmond was doomed to fall, then the president and the government would leave the city, travel south, and set up a new capital in Danville, Virginia, 140 miles to the southwest. The war would go on.

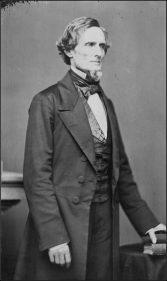

Jefferson Davis at the height of his power.

Davis told the cabinet to pack their most important records and send them to the railroad station. What they could not take, they must burn. The train would leave tonight, and he expected all of them to be on it. Secretary of War John C. Breckinridge would stay behind in Richmond to make sure the evacuation of the government went smoothly, and then follow the train to Danville. Davis ordered the train to take on other cargo, too: the Confederate

treasury

, consisting of half a million dollars in gold and silver coins.

After spending most of the afternoon working at his office, Davis walked home to pack his few remaining possessions. The house was eerily still. His wife, Varina, and their four children had already evacuated to Charlotte, North Carolina. His private secretary, Burton Harrison, had gone with them to make sure they reached safety.

Varina had begged to stay with her husband in Richmond until the end. Jefferson said no, that for their safety, she and the children must go. He understood that she wanted to help and comfort him, he told her, “but you can do this in but one way, and that is by going yourself and taking our children to a place of safety.” What he said next was frightening: “If I live,” he promised, “you can come to me when the struggle is ended.”

On March 29, the day before Varina and the children left Richmond, Davis gave his wife a revolver and taught her how to use it. He also gave her all the money he had, saving just one five-dollar gold piece for himself. Varina and the children left the White House on Thursday, March 30. “Leaving the house as it was,” Varina wrote later, “and taking only our clothing, I made ready with my young sister and my four little children, the eldest only nine years old, to go forth into the unknown.” The children did not want to leave their father. “Our little Jeff begged to remain with him,” Varina wrote, “and Maggie clung to him . . . for it was evident he thought he was looking his last upon us.” The president took his family to the station and put them aboard a train.

While Jefferson Davis spent his last night in the Confederate White House, alone, without his family, he did not know that Abraham Lincoln had left his own White House several days ago and was now traveling in Virginia. Lincoln was visiting the Union army. The Union president did not want to go home until he had won the war. And he dreamed of seeing Richmond.

On March 23 at 1:00

P.M.

, Lincoln left Washington, bound south on the ship

River Queen

. His wife, Mary, came with him, along with their son Tad. A day later the vessel anchored off City Point, Virginia, headquarters of General Grant and the Armies of the United States.

Lincoln met with his commanders to discuss the war. General William Tecumseh Sherman asked Lincoln about his plans for Jefferson Davis. Many in the North wanted Davis hanged if he was captured. Did Lincoln think so, too? Lincoln answered Sherman by saying that all he wanted was for the Southern armies to be defeated. He wanted the Confederate soldiers sent back to their homes, their farms, and their shops. Lincoln didn’t answer Sherman’s question about Jefferson Davis directly. But he told a story.

There was a man, Lincoln said, who had sworn never to touch alcohol. He visited a friend who offered him a drink of lemonade. Then the friend suggested that the lemonade would taste better with a little brandy in it. The man replied that if some of the brandy were to get into the lemonade “unbeknown to him,” that would be fine.

Sherman believed that Lincoln meant it would be the best thing for the country if Jefferson Davis were simply to leave and never return. As the Union president, Lincoln could hardly say in public that he wanted a man who had rebelled against his government to get away without punishment. But if Davis were to escape “unbeknown to him,” as Lincoln seemed to be suggesting, that would be fine.

At City Point Lincoln received reports and sent messages. He haunted the army telegraph office for news of the battles raging in Virginia. He knew that soon Robert E. Lee must make a major decision: Would he sacrifice his army in a final, hopeless battle to defend Richmond, or would he abandon the Confederate capital and save his men to fight another day?

In the afternoon of April 2, Lee telegraphed another warning to Jefferson Davis in Richmond. “I think it absolutely necessary that we should abandon our position tonight,” he wrote. Lee had made his choice. His army would retreat. Richmond would be captured.

Davis packed some clothes, retrieved important papers and letters from his private office, and waited at the mansion. Then a messenger brought him word: The officials of his government had assembled at the station. The train that would carry the president and the cabinet of the Confederacy was loaded and ready to depart.

Davis and a few friends left the White House, mounted their horses, and rode to the railroad station. Crowds did not line the streets to cheer their president or to shout best wishes for his journey. The citizens of Richmond were locking up their homes, hiding their valuables, or fleeing the city before the Yankees arrived. Throughout the day and into the night, countless people left however they could—on foot, on horseback, in carriages, in carts, or in wagons. Some rushed to the railroad station, hoping to catch the last train south. Few would escape.

But not all of Richmond’s inhabitants dreaded the capital’s fall. Among the blacks of Richmond, the mood was happy. At the African church, it was a day of jubilation. Worshippers poured into the streets, congratulated one another, and prayed for the coming of the Union army.

When Jefferson Davis got to the station, he hesitated. Perhaps the fortunes of war had turned in the Confederacy’s favor that night. Perhaps Lee had defeated the enemy after all, as he had done so many times before. For an hour Davis held the loaded and waiting train in hopes of receiving good news from Lee. That telegram never came. The Army of Northern Virginia would not save Richmond from its fate.

Dejected, the president boarded the train. He did not have a private luxurious sleeping car built for the leader of a country. Davis took his seat in a common coach packed with the officials of his government. The train gathered steam and crept out of the station at slow speed, no more than ten miles per hour. It was a humble, sobering departure of the president of the Confederate States of America from his capital city.

As the train rolled out of Richmond, most of the passengers were somber. There was nothing left to say. “It was near midnight,” Postmaster General John Reagan, on board the train, remembered, “when the President and his cabinet left the heroic city. As our train, frightfully overcrowded, rolled along toward Danville we were oppressed with sorrow for those we left behind us and fears for the safety of General Lee and his army.”

The presidential train was not the last one to leave Richmond that night. A second one carried another cargo from the city—the treasure of the Confederacy, half a million dollars in gold and silver coins, plus deposits from the Richmond banks. Captain William Parker, an officer in the Confederate States Navy, was put in charge of the treasure and ordered to guard it during the trip to Danville. Men desperate to escape Richmond and who had failed to make it on to Davis’s train climbed aboard their last hope, the treasure train. The wild mood at the station alarmed Parker, and he ordered his men—some were only boys—to guard the doors and not allow “another soul to enter.”

Once Jefferson Davis was gone, and as the night wore on, Parker witnessed the breakdown of order: “The whiskey . . . was running in the gutters, and men were getting drunk upon it. . . . Large numbers of ruffians suddenly sprung into existence—I suppose thieves, deserters . . . who had been hiding.” If the mob learned what cargo Parker and his men guarded, then the looters, driven mad by greed, would have attacked the train. Parker was prepared to order his men to fire on the crowd. Before that became necessary, the treasure train got up steam and followed Jefferson Davis into the night.

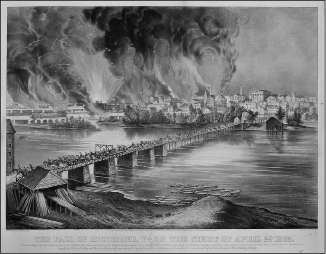

To add to the chaos caused by the mobs, soon there would be fire. And it would not be the Union troops who would burn the city. The Confederates accidentally set their own city afire when they burned supplies to keep them from Union hands. The flames spread out of control and reduced much of the capital to ruins.

The famous Currier and Ives print of Richmond burning, April 2, 1865.

Union troops outside Richmond would see the fire and hear the explosions. “About 2 o’clock on the morning of April 3d bright fires were seen in the direction of Richmond. Shortly after, while we were looking at these fires, we heard explosions,” one witness reported.

On the way to Danville, the president’s train stopped at Clover Station. It was three o’clock in the morning. There a young army lieutenant, eighteen years old, saw the train pull in. He spotted Davis through a window, waving to the people gathered at the station. Later he witnessed the treasure train pass, and others, too. “I saw a government on wheels,” he said. From one car in the rear a man cried out, to no one in particular, “Richmond’s burning. Gone. All gone.”

As Jefferson Davis continued his journey to Danville, Richmond burned and Union troops approached. Around dawn a black man who had escaped the city reached Union lines and reported what Lincoln and U. S. Grant, the commanding general of the Armies of the United States, suspected. The Confederate government had abandoned the capital during the night and the road to the city was open. There would be no battle for Richmond. The Union army could march in and occupy the rebel capital without firing a shot.

The first Union troops entered Richmond shortly after sunrise on Monday, April 3. They marched through the streets, arrived downtown, and took control of the government buildings. They tried to put out the fires, which still burned in some sections of the city. Just a few hours since Davis had left it, the White House of the Confederacy was seized by the Union and made into their new headquarters.

The gloom that filled President Davis’s train eased with the morning sun. Some of the officials of the Confederate government began to talk and tell jokes, trying to brighten the mood. Judah Benjamin, the secretary of state, talked about food and told stories. “[H]is hope and good humor [were] inexhaustible,” one official recalled. With a playful air, he discussed the fine points of a sandwich, analyzed his daily diet given the food shortages that plagued the South, and as an example of doing much with little, showed off his coat and pants, both made from an old shawl, which had kept him warm through three winters. Colonel Frank Lubbock, a former governor of Texas, entertained his fellow travelers with wild western tales.

But back in Richmond, the people had endured a night of terror. The ruins and the smoke presented a terrible sight. A Confederate army officer wrote about what he saw at a depot, or warehouse, where food supplies were stored. “By daylight, on the 3d,” he noted, “a mob of men, women, and children, to the number of several thousands, had gathered at the corner of 14th and Cary streets . . . for it must be remembered that in 1865 Richmond was a half-starved city, and the Confederate Government had that morning removed its guards and abandoned the removal of the provisions. . . . The depot doors were forced open and a demoniacal struggle for the countless barrels of hams, bacon, whisky, flour, sugar, coffee . . . raged about the buildings among the hungry mob. The gutters ran with whisky, and it was lapped up as it flowed down the streets, while all fought for a share of the plunder.”