Bloody Times (6 page)

Authors: James L. Swanson

Safford watched the little group of several men inch through the mob. They were carrying something. It was a man. It was the body of Abraham Lincoln. “Where can we take him?” Safford heard one of the men shout.

Henry Safford seized a candle and held it up so that the men carrying the president could see it. “Bring him in here!” he yelled. He waved the light. “Bring him in here!” He caught their attention. “I saw a man,” said Dr. Leale, “standing at the door of Mr. Petersen’s house holding a candle in his hand and beckoning us to enter.”

The Petersen House, where Lincoln died.

Lincoln’s bearers walked from Ford’s Theatre to the Petersen house. From the safety of her front parlor, Huldah Francis watched them get closer and closer. Soon they were right below her window. When she saw the men carrying Lincoln up the steps, she hurried to put on her clothes. George Francis raced back to the house to join his wife.

Henry Safford invited the men inside. “Take us to your best room,” Dr. Leale commanded. Safford led Dr. Leale and the men carrying Lincoln into the front hall. On the right, a narrow staircase led up to the second floor. On the left was a closed door.

Leale had asked for the “best room.” That would be the one where George and Huldah Francis lived. Safford took the handle of the door to their parlor and turned it. Locked! Safford headed deeper into the dim hallway and stopped at a second door on the left, the one to the Francises’ bedroom. Also locked! Behind that door, Huldah Francis was dressing.

There was just one room left, the smallest one on the first floor. Safford turned the doorknob. It was unlocked. And the room was empty. The boarder, Private William Clarke, had gone out for the evening to celebrate the end of the war.

It was enough for Leale. He ordered the bearers to carry Lincoln into the room and lay him on the bed.

A few minutes later Mary Lincoln appeared in the doorway of the Petersen house. Major Rathbone and Clara Harris had helped her through the wailing mob in the street and into the house. George Francis saw her arrival. “She was perfectly frantic,” he remembered. “‘Where is my husband! Where is my husband!’ she cried, wringing her hands.” Moments later she reached the back room, where she found Lincoln lying on a bed. Dr. Leale and two other doctors, who had also been in the audience at Ford’s, were bent over Lincoln. George Francis watched as Mary saw her husband. “As she approached his bedside she bent over him, kissing him again and again, exclaiming ‘How can it be so? Do speak to me!’”

Leale asked Mary to go into the next room while the doctors examined her husband. She agreed. Henry Rathbone and Clara Harris brought Mary to the front parlor and seated her on a large sofa. Rathbone felt light-headed. Moments after John Wilkes Booth shot the president, the actor had stabbed Rathbone in the arm. The wound was deep, and the cut would not stop bleeding. He sat down in the hall and then fainted. When he awoke later, he was picked up from the floor and delivered to his house. He would live.

The doctors dragged William Clarke’s bed away from the walls so that they could see Lincoln better. Then they pushed all the chairs close to the bed. Leale ordered everyone except the two other doctors to leave the room. They stripped their patient and searched his body for other wounds.

In the front parlor Mary Lincoln was coming apart. When Clara Harris sat beside her on the sofa and tried to comfort her, Mary could not take her eyes off Clara’s bloodstained dress: “My husband’s blood!” she cried. “My husband’s blood.” The First Lady did not know that it was Henry Rathbone’s blood, not the president’s, on Clara’s dress. If Mary had examined her own dress, she would have been horrified, for it did bear the stains of her husband’s blood.

Mary Lincoln needed help. Clara Harris would not do—Mary hardly knew her. The First Lady had few friends in Washington, and now she asked for them all: Mary Jane Welles, wife of navy secretary Gideon Welles; Elizabeth Keckly, her black dressmaker; and Elizabeth Dixon, wife of a United States senator. Messengers ran off in search of the women. While she waited for her friends to arrive at her side, Mary, in torment, sat on the sofa. The crowd was just outside the windows. She could hear their voices.

Elizabeth Dixon was the first of Mary’s friends to arrive. She saw a gruesome scene that horrified her: “On a common bedstead covered with an army blanket and a colored woolen coverlid lay stretched the murdered President his life blood slowly ebbing away,” she remembered. “The officers of the government were there & no lady except Miss Harris whose dress was spattered with blood as was Mrs. Lincoln’s who was frantic with grief calling him to take her with him, to speak one word to her. . . . I held and supported her as well as I could & twice we persuaded her to go into another room.”

Throughout the night Dr. Leale watched Mary Lincoln stagger from the front parlor into the bedroom. “Mrs. Lincoln accompanied by Mrs. Senator Dixon came into the room several times during the course of the night. Mrs. Lincoln at one time exclaiming, ‘Oh, that my Taddy might see his Father before he died’ and then she fainted and was carried from the room.”

Tad was not at the Petersen house with his grieving mother and his dying father. Earlier one of the men who had rushed out of Ford’s had run to nearby Grover’s Theatre. Someone from the audience remembered what happened next. “Miss German had just finished a song called ‘Sherman’s March Down to the Sea’ and was about to repeat it,” he recalled, “when the door of the theatre was pushed violently open and a man rushed in exclaiming ‘turn out for Gods sake, the President has been shot in his private box at Ford’s Theatre.’” The theater manager also announced the news from the stage. This was how Tad Lincoln, watching the play, learned that his father had been shot.

Tad was brought not to the Petersen house but to the White House by the doorkeeper. By the time he got home, his older brother, Robert Lincoln, had already left to join his parents. Without his mother or older brother to comfort Tad, or even explain to him what had happened to his father, the frightened boy spent the night with servants in the near-empty mansion.

Shortly after 8:00

A.M.

the next morning, Mary and Robert returned to the White House and informed Tad that his beloved “Pa” was dead. Tad felt again the fear and pain that he had suffered three years before when his brother Willie had died. During the long night, not once had Robert or Mary Lincoln gone to Tad. Nor had they ordered a messenger to bring him to the Petersen house and his dying father. It was the first troubling sign of how, in the days to come, Mary Lincoln’s grief caused her to neglect her miserable and lonely little boy.

While Tad stayed alone at the White House through the night of April 14, Leale and the other doctors examined the president. More doctors arrived soon. But nothing could save Lincoln. By midnight it had become a death watch. All they would do now was observe and wait.

A second assassin had struck in Washington the night of April 14. At 10:15

P.M.

, about the same time that John Wilkes Booth shot the president, another assailant had invaded the home of the secretary of state. William Seward, bedridden from a carriage accident, lay in his bed. The attacker stabbed and slashed him almost to death; wounded an army sergeant serving as Seward’s nurse; and stabbed a State Department messenger. He also struck Seward’s son with a pistol, crushing his victim’s skull and leaving him unconscious.

Runners carried the news of the attack on Seward to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, who were at their homes preparing for bed. Neither had yet heard about the assassination of the president. Each man raced by carriage to Seward’s mansion. There they first heard rumors of another attack, this one upon the president at Ford’s Theatre. Together Stanton and Welles drove a carriage to Tenth Street and arrived at the Petersen house before midnight.

Stanton barreled his way though the crowded hallway. He knew quickly that Lincoln was a dead man. There was nothing he could do for him. Except work. There was much to do. Stanton prepared himself for the long night ahead. He would lead the investigation of the crime, interview witnesses, send telegrams, launch the manhunt for Booth and his accomplices, and take precautions to prevent more assassinations.

As news of the assassination spread through Washington, many important public officials hurried to the Petersen house. Some came and went. Others stayed, sometimes for hours. Welles decided that at least one person should remain by Abraham Lincoln’s side until the end. He volunteered. And he would record in his diary what he saw. Lincoln was stretched out “diagonally across the bed, which was not long enough for him. He had been stripped of his clothes. His large arms were of a size which one would scarce have expected from his spare form. His features were calm and striking. I have never seen them appear to better advantage, than for the first hour I was there. The room was small and overcrowded. The surgeons and members of the Cabinet were as many as should have been in the room, but there were many more, and the hall and other rooms in front were full.”

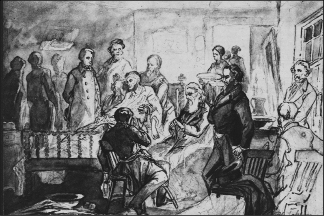

The Petersen House deathbed vigil, sketched by an artist from the Army Medical Museum.

Welles remembered that Lincoln, earlier that day, had told of a dream he’d had. In the dream Lincoln found himself aboard a ship sailing rapidly toward shore. The president said that he’d had this vision before many great battles of the Civil War. Had a warning of his own assassination come to Abraham Lincoln in the night? As Gideon Welles sat beside his dying leader, he did not know that, several days earlier, Lincoln had dreamed a far more vivid nightmare of death.

A few days before the assassination, the president, Mary Lincoln, and two or three friends were gathered. One observed that Lincoln was in a “melancholy, meditative mood.” The president had talked about the meaning of dreams. Mary asked her husband if he believed in dreams. “‘I can’t say that I do,’” he replied, “‘but I had one the other night which has haunted me ever since.’” Lincoln told what his dream had been.

“‘There seemed to be a death-like stillness about me. Then I heard . . . sobs, as if a number of people were weeping. I thought I left my bed and wandered downstairs. There the silence was broken by the same pitiful sobbing, but the mourners were invisible. I went from room to room; no living person was in sight. . . . It was light in all the rooms; every object was familiar to me; but where were all the people who were grieving as if their hearts would break? I was puzzled and alarmed. What could be the meaning of all this? . . . I kept on until I arrived at the East Room, which I entered. There I met with a sickening surprise. Before me was a catafalque [a platform], on which rested a corpse. . . . Around it were soldiers who were acting as guards. . . . ‘Who is dead in the White House?’ I demanded of one of the soldiers. ‘The President,’ was his answer; ‘he was killed by an assassin!’ Then came a loud burst of grief from the crowd, which awoke me from my dream. I slept no more than night . . .”