Bloody Times (8 page)

Authors: James L. Swanson

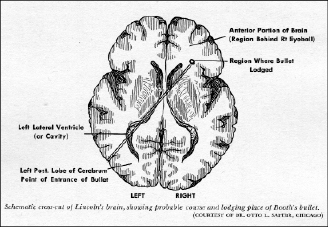

The bullet’s fatal path.

Edwin Stanton went through Lincoln’s wardrobe to choose the suit he would be buried in. Abraham Lincoln had never cared much about his clothes; he usually wore whatever he owned until it was worn out. But Stanton did find one new black suit that he thought would do. He watched as the embalmers fitted the president with a white cotton shirt, attached a black bow tie under his collar, and dressed him in the clothes Stanton had chosen.

Lincoln’s corpse was ready for his funeral. But Edwin Stanton had no time to organize it. He would have to choose someone else to set in motion Washington’s grand farewell to Abraham Lincoln.

Stanton picked George Harrington, assistant secretary of the treasury. Harrington would take charge of all events in Washington honoring the late president. But at the moment there were no events to take charge of. No American president had ever been murdered. It would be up to Harrington to figure out how the capital should pay tribute to its first assassinated president.

Now that Lincoln’s body was prepared for burial, a few visitors were allowed to pass into the White House, climb the stairs, enter the dark chamber, and view the body. Only relatives, close friends, and high officials were given permission. Mary Lincoln’s friend and dressmaker Elizabeth Keckly was one of them.

After the president had been shot, Mary had sent a messenger summoning Keckly to her side. She had rushed to the White House, but guards would not let the free black woman enter. Keckly did not see Mary until the next day.

“I shall never forget the scene,” Keckly wrote afterward, “the wails of a broken heart, the unearthly shrieks.” She worried about Tad. He was silent in his own grief and frightened by his mother’s outbursts. “Sometimes he would throw his arms around her neck,” she described, “and exclaim, between his broken sobs, ‘Don’t cry so, Momma! Don’t cry, or you will make me cry too! You will break my heart.’”

Keckly comforted Mary and then asked to see Abraham Lincoln. “[Mrs. Lincoln] was nearly exhausted with grief, and when she became a little quiet, I received permission to go into the Guest Room, where the body of the President lay in state,” she wrote. “When I crossed the threshold of the room I could not help recalling the day on which I had seen little Willie [Lincoln] lying in his coffin where the body of his father now lay. I remembered how the president had wept over the pale beautiful face of his gifted boy, and now the President himself was dead.”

Strangely, Mary Lincoln did not make a private visit to her husband. Her last nightmare vision of him as he lay dying was too terrible. She could not bear to walk the short distance from her bedchamber to the Guest Room and look upon his face now. Tad stayed in her bedchamber with her. We don’t know whether Tad’s older brother, Robert, took the younger boy to the Guest Room to view their father, just as, three years before, Abraham had carried Tad from his bed to view his brother Willie in death.

For three days and two nights, Lincoln’s body rested on a table in the White House. Except for a few visitors and the guards standing around his corpse, he was alone. The only sounds in the house were those Lincoln would have remembered from childhood—wood saws cutting, hammers pounding nails, carpenters at work. Workmen in the East Room were building the platform upon which his elaborate coffin, not yet finished, would soon rest, and were building the benches upon which the funeralgoers would sit.

Outside this room, the nation was in upheaval. The assassin John Wilkes Booth had escaped, and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton was directing the manhunt to capture him. Stanton worried that there might be other assassins, perhaps plotting attacks on the highest officials of Lincoln’s government. Stanton ordered every one of them protected by a military guard around the clock.

And Confederate president Jefferson Davis was unaccounted for. Stanton thought that Davis planned to rally the South to fight on. Many newspaper stories in the North suggested that Lincoln’s murder was part of Davis’s plan to win the war. Even if that wasn’t true, there was still danger from Confederate troops. Lee had surrendered, but he did not command the Confederacy’s only army. There were still other armies in the field ready to fight.

As Stanton worked and worried, George Harrington labored long hours to organize the grandest funeral ceremony in American history. This was his plan:

On Tuesday, April 18, the public would be able to come to the East Room of the White House and view the president’s body.

On Wednesday, April 19, there would be a funeral, and then a procession to carry Abraham Lincoln’s body to the Capitol.

On Friday, April 21, another funeral procession would take the body to the train station, where it would be taken to the place he would be buried.

Many questions remained unsettled. For how many hours should the White House be kept open for the public to view the remains? How many people per hour could squeeze through the doors? Who should be invited to the funeral? And where could it be held? The East Room was the biggest room in the White House, but it could never hold everyone who would want to say a last farewell to Lincoln. And where would they find enough chairs for all of them? George Harrington needed help.

He called a meeting of several of the most important army officers in Washington. They had much work to do and little time—just sixty-eight hours to plan Abraham Lincoln’s funeral.

Harrington’s duties would end once the ceremonies in Washington were over. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton had taken responsibility for the next stage of the president’s journey.

But one important question remained. Where would Abraham Lincoln be buried? In Washington? Under the United States Capitol, in an empty crypt once intended for but never occupied by George Washington’s body? Or would Mary Lincoln take the body home to Illinois? Would he be laid to rest in Chicago, its most important city, or in Springfield, Lincoln’s home for the past twenty-four years? What about Kentucky, where he had been born? It was up to Mary Lincoln to decide. At last she and her son Robert settled on Springfield.

Now the secretary of war was able to plan the route of the train that would carry Lincoln’s body. That train

could

head for Illinois by the shortest and most direct route. But that might not be best. Four years earlier, in 1861, after Abraham Lincoln had been elected president of the United States, he had taken a long train trip through several of the major Northern states. He wanted to see the American people and let them see him. He gave speeches, greeted important officials, mingled with ordinary citizens, and took part in ceremonies. For Abraham Lincoln that journey was a symbol of the bond between himself and the American people.

Now he was dead. In their grief, Americans had not forgotten the train ride of 1861. At the War Department telegrams began to pour in from the cities and towns that had seen him on his journey east from the prairie four years ago. Send him back to us, they asked. Edwin Stanton liked the idea. The assassination of President Lincoln was a national tragedy. But the American people could not come from all over the country to view the president’s body, attend the funeral, or march in the procession. Then why couldn’t Abraham Lincoln go to them?

It could be done. There was only one thing in the way—the president’s widow. First Mary Lincoln would have to agree.

Stanton talked to her. Might she, he asked, consider soothing the grief of the American people by agreeing to send his body by train through the great cities of the Union? From Washington the train would head to Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York, then make the great turn west, passing through Ohio and Indiana and into northern Illinois, then make a final turn south from Chicago, down through the prairies and home to Springfield.

There was one more thing. The people wanted to see their Father Abraham, not just his closed coffin. They wanted to look upon his face. That meant his coffin would have to be open for a journey of more than sixteen hundred miles. To Mary Lincoln the idea seemed ghoulish. The idea of exhibiting her dear husband’s remains for all to see horrified her. But at the same time, she liked thinking of a grand funeral pageant that would show what a great man Lincoln had been. She said yes.

At the Treasury Department George Harrington began adding up the number of people who had to receive an invitation to the White House funeral. Letters and telegrams begging for tickets to the funeral or positions in the procession poured in. While Harrington worked and planned, Abraham Lincoln spent his last night in the White House.

George Harrington, the man who planned all Lincoln funeral events in Washington.

Two days after the president died, the coffin was ready. Soldiers carried it to the second-floor Guest Room and placed it on the floor. They lifted the president’s body from the table where he had lain since Saturday afternoon. The soldiers carried him to the coffin—it looked too small. How would they fit him into it? Abraham Lincoln was six feet, four inches tall, and the coffin turned out to be just two inches taller. It was a snug fit. If they had tried to bury him in his boots, he would have been too tall.

The soldiers lifted the coffin and carried it down the stairs. They took it to the center of the East Room and rested it upon a platform. The coffin itself was expensive and magnificent, probably not what Lincoln would have chosen for himself. Why, it had cost almost as much as he paid for his house in Springfield.

Lincoln’s body lay waiting in the East Room for his funeral. It would not be the first funeral of someone from the Lincoln family in the White House. Three years earlier, Lincoln had attended the funeral of his son Willie. It was, he said, “the hardest trial of my life.”

William Wallace Lincoln, age eleven, was the president’s favorite son. Tall and thin, Willie looked like his father. His mind worked, Abraham said, in ways that reminded him of himself. Willie was his father’s true companion in the White House and the favorite of many of those who lived and worked there. Lincoln loved no one more.

In February 1862 both Tad and Willie fell ill with a fever. They got worse, and the president watched over them with a keen eye. During the next two weeks, they became seriously ill. The

Evening Star

began printing reports on how they were doing. On February 20 the newspaper wrote, “BETTER.—We are glad to say that the President’s second son—Willie—who has been so dangerously ill seems better to-day.”

But this last report was wrong. Willie Lincoln died the afternoon of February 20, at 5:00

P.M.

Lincoln cried out to his secretary, “My boy is gone—he is actually gone!” Willie, he said, “was too good for this earth . . . but then we loved him so. It is hard, hard to have him die!”

Willie’s body was laid out in the Green Room of the White House as arrangements were made for his funeral. While the boy’s body lay a short distance away, a man looking for a government job made the mistake of bothering Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln had made it a lifelong habit to control his temper, and it was a rare thing when he showed anger in public. But if pushed too far, Lincoln would sometimes unleash his wrath—as he did at this unwelcome visitor.

“When you came to the door here, didn’t you see the crepe on it?” he demanded. “Didn’t you realize that meant somebody must be lying dead in this house?”

“Yes, Mr. Lincoln, I did. But what I wanted to see you about was very important.”

“That crepe is hanging there for my son; his dead body at this moment is lying unburied in this house, and you come here, push yourself in with such a request! Couldn’t you at least have the decency to wait until after we had buried him?”