Bloody Times (11 page)

Authors: James L. Swanson

Davis had almost decided to leave the country, but when these soldiers and their horses arrived in Charlotte, he changed his mind. “Troops began to come into Charlotte, however . . . and there was much talk among them of crossing the Mississippi and continuing the war,” remembered Stephen Mallory. “They seemed determined to get across the river and fight it out, and whenever they encountered Mr. Davis they cheered and sought to encourage him. . . . He became indifferent to his own safety, thinking only of gathering together a body of troops to make head against the foe and so arouse the people to arms.”

At 6:00

A.M.

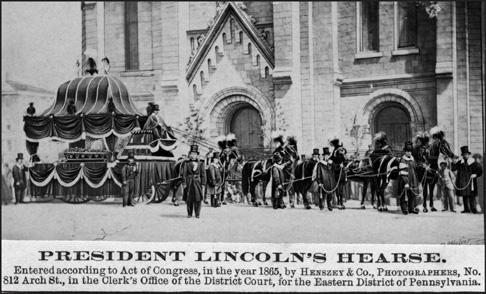

on Friday, April 21, one week after the assassination, an escort arrived at the Capitol to accompany Lincoln’s body to the funeral train. Soldiers removed the coffin from the platform, carried it down the stairs, and placed it in a horse-drawn hearse. It was not supposed to be a grand or official procession. There were no drummers, no bands, and no train of marchers. It was just a short trip from the east front plaza of the Capitol to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad station.

But that did not stop the crowds. Several thousand onlookers lined the route and surrounded the station entrance. Edwin Stanton supervised the procession himself to make sure that the transfer of Abraham Lincoln’s body from the Capitol to the funeral train was done with simplicity, dignity, and honor.

Earlier that morning another hearse had arrived at the station. It had come from Oak Hill Cemetery in Georgetown. When the soldiers carried Abraham Lincoln aboard his private railroad car at 7:30

A.M.

, the body of his dead son Willie was already there, waiting for him. Once Lincoln had planned to collect the boy himself and take his coffin home. Now two coffins shared the presidential car.

Members of the honor guard took their places beside the coffin. The train would not take aboard the hearse and horses which had carried Lincoln’s body to the railroad station. Instead, in every city where the train would stop for funeral services, local officials would provide a horse-drawn hearse to take the coffin from the train.

Mourning ribbon worn by members of the United States Military Rail Road.

At 7:50

A.M.

Robert Lincoln boarded the train. He would not ride all the way to Illinois. He planned to ride the train part of the way, then return to Washington to wrap up his father’s affairs. Mary Lincoln did not board the train; nor did she appear at the station to see her husband off. And she did not allow Tad to go.

Tad should have gone to the station and then ridden with his father all the way back to Illinois. After Willie’s death, Tad and his father were always together. Sometimes Tad fell asleep in the president’s office, and Lincoln would lift the boy over his shoulder and carry him off to bed. Tad loved to go on trips with his father. He loved to see soldiers, and he enjoyed wearing—and posing for photos—in a child-size Union army officer’s uniform, complete with a tiny sword, that Lincoln had given him. Tad would have marveled at the sights and sounds along the sixteen-hundred-mile journey. And he would have been proud of, and taken comfort from, the honor paid to his father. But, kept in the White House, Tad saw none of this.

Two more men boarded the train as it waited at the station. In the days to come, the success or failure of this mission would depend upon their work. They were the “body men,” embalmer Dr. Brown and undertaker Frank Sands. For the next thirteen days, it would be their job to keep Abraham Lincoln’s corpse looking as lifelike as possible.

At exactly 8:00

A.M.

the wheels of the engine turned, and the eight railroad cars it pulled began to move.

Lincoln’s train would reach Baltimore in four hours. No one knew exactly what would happen at the first stop outside Washington. No one anticipated what was to come: bonfires, torches, arches of flowers, hand-painted signs, banners, and masses of people along the way at all hours of the day or night. Parents held out sleepy-eyed infants and even uncomprehending babes in arms, so that one day they could tell their children: “

You

were there. You saw Father Abraham pass by.”

Without anyone in the government ordering it, this train became more than the funeral for one dead man. Somewhere between Washington and Springfield, the train became a symbol of the cost of the Civil War. It represented a mournful homecoming for all the men—Union and Confederate—who had died on the battlefield. It was as if an army of the dead—and not one solitary man—rode aboard that train.

Lincoln’s funeral car.

But this transformation had not yet taken place as the train approached Baltimore. The whole state of Maryland, and Baltimore in particular, were known for being unfriendly to Lincoln. Four years ago, on his way to become president, Lincoln’s train had traveled through Baltimore. People there were rumored to be plotting to kill him. Lincoln passed through the city in secrecy in the middle of the night.

But now all was peaceful as the train arrived at Baltimore at 10:00

A.M.

Townsend telegraphed Stanton promptly: “Just arrived all safe.” Thousands of sincere mourners stood in heavy rain to await the president. The honor guard aboard the train carried the coffin from the car and placed it in a hearse drawn by four black horses.

The hearse was designed to display the coffin. According to one spectator, “The body of this hearse was almost entirely composed of plate glass, which enabled the vast crowd . . . to have a full view of the coffin. The supports of the top were draped with black cloth and white silk, and the top of the car was handsomely decorated with black plumes.”

A procession got under way and marched to the Merchant’s Exchange. It took three hours to reach Calvert Street. The column halted, the hearse drove to the southern entrance of the Exchange, and Lincoln’s bearers carried him inside. There they laid the coffin beneath a dome, upon a platform about three feet tall, with columns on the four corners. A canopy fourteen feet tall was draped with black cloth, trimmed with silver fringe, and decorated with silver stars. Around the platform, Townsend saw, “were tastefully arranged evergreens, wreaths, calla-lilies, and other

choice

flowers.”

In Baltimore there would be no ceremonies, sermons, or speeches; there was no time for that. Instead, as soon as Lincoln was in position, guards threw the doors open and the public mourners filed in. Over the next four hours, thousands viewed the body. The upper part of the coffin was open to reveal Lincoln’s face and chest.

In Baltimore, Edward Townsend established two rules. First, no one except the officers and men of the United States army traveling aboard the train was ever allowed to touch the president’s coffin. Townsend was firm: “No bearers, except the veteran guard, were ever suffered to handle the President’s coffin.” Second, Townsend had forbidden mourners to get too close to the open coffin, to touch the president’s body, to kiss him, or to place anything, including flowers, in the coffin. Any person who violated these rules would be seized at once and removed from Lincoln’s presence.

At about 2:30

P.M.

, with thousands of citizens, black and white, still waiting in line to see the president, local officials ended the viewing. Lincoln’s bearers closed the coffin and carried it back to the hearse. A second procession delivered Lincoln’s body to the North Central Railway station in time for the scheduled 3:00

P.M.

departure for Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

The first stop had gone well. General Townsend sent a telegram to the Secretary of War:

BALTIMORE, April 21, 1865.

Hon. E. M. STANTON,

Secretary of War:

Ceremonies very imposing. Dense crowd lined the streets; chiefly laboring classes, white and black. Perfect order throughout. Many men and women in tears. Arrangements admirable. Start for Harrisburg [Pennsylvania] at 3 p.m.

E. D. TOWNSEND,

Assistant Adjutant-General

On the way to Harrisburg, the train stopped briefly at York, where the women of the city had asked permission to lay a wreath of flowers upon Lincoln’s coffin. Edward Townsend allowed six women to come aboard. While a band played a

dirge

and bells tolled, they approached the funeral car, stepped inside, and laid their large wreath of red and white flowers on the coffin. The women wept bitterly as they left the train. Soon, at the next stop, their flowers would be pushed aside in favor of others.

The train arrived at Harrisburg, capital of Pennsylvania, at 8:20

P.M.

on Friday, April 21. Townsend reported to Edwin Stanton: “Arrived here safely. Everything goes on well.” It was dark and a heavy rain was falling. “Slowly through the muddy streets, followed by two of the guard of honor and the faithful sergeants, the hearse wended its way to the Capitol,” Townsend wrote.

Even in the rain, thousands of onlookers followed the hearse to the State House. To the boom of cannon firing once a minute, the coffin was carried inside and laid on a platform. Lincoln was on view until midnight, and again at 7:00

A.M.

the next morning, Saturday, April 22. The coffin was closed at 9:00

A.M.

At 10:00

A.M.

, as a band played, drums beat, and soldiers marched or rode their horses, a hearse carried Lincoln back to the train.

On April 22, while Abraham Lincoln was on the move, Jefferson Davis had still not left Charlotte, North Carolina. Lincoln’s murder had placed Davis in greater peril, but the Confederate president didn’t rush to escape. Davis acted as a man making a careful retreat, not fleeing for his life.

Davis was not the only one who wanted to keep fighting. General Wade Hampton wrote to him again on April 22, encouraging him to make a run for Texas. “If you should propose to cross the Mississippi River I can bring many good men to escort you over,” he told Davis. “My men are in hand and ready to follow me anywhere . . . I write hurriedly, as the messenger is about to leave. If I can serve you or my country by any further fighting you have only to tell me so. My plan is to collect all the men who will stick to their colors, and to get to Texas.”

Lincoln’s funeral train left Harrisburg forty-five minutes early. At every station, and along the railroad tracks between them, people gathered to watch the train pass by. For miles before Philadelphia, unbroken lines of people stood and watched along both sides of the tracks.

The train arrived in Philadelphia before 5:00

P.M.

on Saturday, April 22. As soon as the engine rolled into the station, a single cannon shot announced to the city that Lincoln had arrived. Townsend sent off a telegram to Stanton: “We have arrived here safely. Everything is in good order.” The crowd was immense.