Bloody Times (15 page)

Authors: James L. Swanson

Lincoln was home, back at the Great Western Railroad Depot where his journey began four years ago, on February 11, 1861. When he left for Washington that morning, he realized that he might never return. He stood in the last car of the train, looked at the faces of his neighbors, and spoke:

My friends, no one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feelings of sadness at this parting. To this place, and the kindness of these people, I owe everything. Here I have lived a quarter of a century, and have passed from a young man to an old one. Here my children have been born, and one is buried. I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington. Without the assistance of the Divine Being who ever attended him, I cannot succeed. With that assistance I cannot fail. Trusting in Him who can go with me, and remain with you, and be everywhere for good, let us confidently hope that all will yet be well. To his care commending you, as I hope in your prayers you will commend me, I bid you an affectionate farewell.

Not long after Lincoln’s remains arrived in Springfield, Jefferson Davis arrived in Washington, Georgia. By this time Davis’s escort was weary and unhappy. They wanted to go home. John Reagan knew what else they wanted: “Before reaching Washington, [Davis’s] cavalry, knowing that they were guarding money, demanded a portion of it,” he remembered. If the government failed to pay them, they were going to seize the money. Breckinridge and the officers commanding the cavalry gave in and handed out a portion of the money.

It was in Washington that Judah Benjamin, the secretary of state, decided to leave Davis and make his own escape. The president’s pace was too slow for Benjamin’s taste, and he thought he would have a better chance to avoid capture on his own. He had never been comfortable riding a horse and set out in a carriage. Reagan spoke to him before he set off and asked where he was going. “To the farthest place from the United States,” Benjamin responded, “if it takes me to the middle of China.”

Others pushed Jefferson Davis to try to escape, once again urging him to strike out alone or with one companion and get out of the country or over the Mississippi. He responded, “I shall not leave Confederate soil while a Confederate regiment is on it.”

In Washington, Georgia, the people welcomed their president as if he rode at the head of a triumphant procession. Eliza Andrews, the twenty-four-year-old daughter of a judge and a plantation owner, described the scene:

“About noon the town was thrown into the wildest excitement by the arrival of President Davis. . . . He rode into town at the head of his escort . . . and as he was passing by the bank . . . several . . . gentlemen were sitting on the front porch, and the instant they recognized him they took off their hats and received him with every mark of respect due the president of a brave people. When he reined in his horse, all the staff who were present advanced to hold the reins and assist him to dismount.” This was the warm welcome that Greensboro and Charlotte, North Carolina, had withheld from Davis.

Jefferson Davis, his remaining friends, and soldiers stayed in Washington for a few days. But it could not be long. A letter from Varina and a dispatch from Breckinridge again urged Davis to flee. If he hoped to avoid capture, his advisers were right. Jefferson Davis needed to move fast to the Mississippi River or Florida.

In Springfield the honor guard removed Lincoln’s body from the train and took it to the Statehouse, where they laid it on a platform. This morning, for the first time since the funeral train left Washington, the honor guard also removed Willie’s coffin from the presidential car.

Springfield was not a great American city, and its people knew they could not hope to rival the displays of Washington, Philadelphia, New York City, or Chicago. Lincoln’s hometown even had to borrow a hearse from St. Louis. However, Springfield meant to prove that Abraham Lincoln meant more to his hometown than he did to any other city in the country.

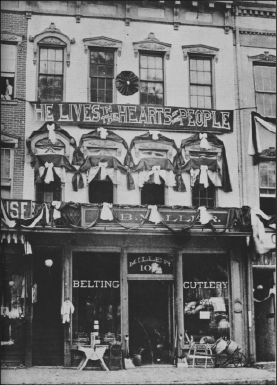

Springfield welcomes Lincoln home.

The embalmer and undertaker opened Lincoln’s coffin. He had been dead for eighteen days. Only chemicals and makeup had kept him presentable during the journey. At the beginning, at the White House funeral, Lincoln’s face had looked almost natural. He had changed along the way. The face continued to darken, and more and more white face powder had to be applied. Lincoln no longer resembled a sleeping man. Now he looked like a ghastly, pale, waxlike statue.

The doors to the Statehouse opened to the public at 10:00

A.M.

on May 3 and stayed that way for twenty-four hours. It was the first round-the-clock viewing since Lincoln had died. During the night trains continued to arrive in Springfield, and people without lodgings wandered the streets until dawn.

By 10:00

A.M.

on May 4, seventy-five thousand people had passed by the presidential body. The coffin was removed from the Statehouse and placed in the hearse waiting on Washington Street. The procession began at 11:30

A.M.

, passing by Lincoln’s home, then heading to Oak Ridge Cemetery, about a mile and a half from town. Lincoln’s guards removed his coffin from the hearse, carried it into the limestone tomb, and laid it on a marble slab. Willie’s coffin rested near him.

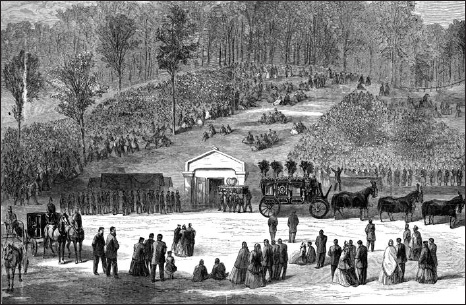

The Springfield tomb.

Bishop Matthew Simpson, who had been at the White House funeral, was there to speak. He read the speech that Lincoln had given when he had been sworn in for his second term as president, with its famous lines calling for “malice toward none” and “charity for all.” Simpson called for forgiveness of the Southern people: “We will take them to our hearts,” he said. But the bishop scorned Jefferson Davis and other Confederate leaders. “Let every man who . . . aided in beginning this rebellion, and thus led to the slaughter of our sons and daughters, be brought to speedy and certain punishment. Let every officer . . . who . . . has turned his sword against . . . his country, be doomed to a felon’s death. This . . . is the will of the American people. . . . There shall be no peace to rebels,” he declared.

This shocking, tomb-side lust for revenge would have horrified Lincoln.

Lincoln’s pastor, the Reverend Dr. Gurley, gave a last prayer, which was followed by a funeral hymn. There was nothing more to say. They closed the iron gates and locked Abraham and Willie Lincoln in their tomb. Then everybody went home.

In Washington, Georgia, a few hundred citizens honored Jefferson Davis on his second day with them. “Crowds of people flocked to see him,” wrote Eliza Andrews, “and nearly all were melted to tears.” Not only did the townspeople gather around Davis, but they put together an enormous feast. “The village sent so many good things for the President to eat,” recalled Eliza, “that an ogre couldn’t have devoured them all, and he left many little delicacies . . . to people who had been kind to him.”

It was in Washington that Stephen Mallory, the secretary of the navy, left Jefferson Davis. Davis understood that it was time for Mallory to return to his family. He took time to compose a warm farewell letter. Davis did not know it, but it was the last letter he would write as president of the Confederate States of America.

Davis then finally agreed to take the action he should have chosen days ago. He would start south with ten men, his officers, and his secretary, leaving Breckinridge to finish up any business of the War Department and John Reagan to handle anything dealing with the Post-office Department or the Treasury.

Eliza Andrews watched Davis ride out the night of May 4. She had heard rumors that the Union army did not actually want to capture Davis: “The general belief is that Grant and the military men, even Sherman, are not anxious for the ugly job of hanging such a man as our president, and are quite willing to let him give them the slip, and get out of the country if he can. The military men, who do the hard and cruel things in war, seem to be more merciful in peace than the politicians who stay at home and do the talking.”

For the past three weeks, the newspapers had told the story of Lincoln’s last journey. Every stop of the train, every city it passed through, every person who marched in the processions, every detail of the black drapery and silver trim and lavish flowers that decorated the hearses and the viewing chambers—no detail was too unimportant for the papers to print or for people to read.

It was impossible for everyone in the country to hurry to Washington, D.C., for the procession, funeral, and viewing there or to go to the cities where the funeral train would stop. These stories carried every American who read them to Lincoln’s side and allowed them to imagine what it must have been like to behold his face or to watch his coffin pass by. Newspapers made it possible for the American people to ride aboard that train.

As they viewed Lincoln’s corpse, watched his funeral train pass by, or eagerly read the newspaper stories, Americans mourned the death of their president. They honored his achievements: He had won the war, saved the Union, and set men free. They vowed to bear the burden of his unfinished work. And they declared, by the tributes they paid to him, that his great cause was worth fighting and dying for.

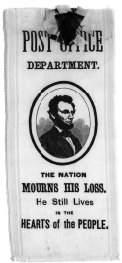

Mourning ribbon worn in Washington by Post Office workers for the April 19, 1865, funeral procession.

For whom did all these people mourn? For their dead president, of course. But this outpouring of sorrow was not for just one man. They mourned for all the men—every son, every brother, every husband, and every father—lost in that war. It was as though, on that train, in that coffin, they were

all

coming home.

On the day that Lincoln was at last buried, more than sixteen hundred miles away in Washington, D.C., offices were closed, public buildings were still draped in black, and flags flew at half staff. Army officers wore black crepe ribbons around their coat sleeves. John Wilkes Booth lay in a secret, unmarked grave on the grounds of the United States Army penitentiary. Booth’s coconspirators awaited trial. Secretary of State Seward was recovering from his wounds.

At the White House Abraham Lincoln’s office was still just as the president left it on the afternoon of April 14. His widow was still living there. She had refused to leave, which meant that the new president, Andrew Johnson, could not move in. It had become the subject of much talk. At the Petersen house Private William Clarke went to bed each night covered by the same quilt that had warmed the dying president.

Now Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton could focus his attention on the capture of Jefferson Davis. Lincoln’s journey was over at last. But Jefferson Davis still had further to go.

On May 5 Jefferson Davis and the small group of men still traveling with him made a camp near Sandersville, Georgia. The next day Burton Harrison directed Varina Davis and the train of wagons carrying her property to camp off the road near Dublin, Georgia. Around midnight Davis’s party stumbled upon her campsite. More than a month had gone by since Davis had seen his family. They traveled together on May 7.