Bloody Times (13 page)

Authors: James L. Swanson

Later Townsend sent yet another telegram, describing the photograph. It was not, as Stanton probably feared, a close-up view of Lincoln’s face, but a picture of the coffin, draped in black and surrounded by flags, as it had been viewed by thousands of New Yorkers. “The effect of the picture would be general,” Townsend assured Stanton, “taking in the whole scene, but not giving the features of the corpse.”

Stanton did not punish Townsend for what he had done. But he did order the photographs and the glass plate negatives seized. To this day no one knows what became of them. Perhaps Stanton destroyed the prints and smashed the glass negatives. Perhaps he stored them somewhere no one has ever found them.

But Stanton could not resist saving for himself at least one image of Lincoln’s corpse. Almost a century after Lincoln’s death, a sole surviving photograph made from one of the negatives was discovered, stored with Stanton’s personal files. Perhaps Stanton saved it for history. Or perhaps he intended that it should never be seen, and that it remain for his eyes only, a vivid reminder of the death of Abraham Lincoln.

The notorious Gurney image, taken inside New York City Hall. Edward D. Townsend stands at the foot of the coffin in the only surviving photograph of Lincoln in death.

On April 26 two events took place far from New York that were each much more important than a photograph of a coffin. On that day, before dawn, at a farm near Port Royal, Virginia, soldiers caught up with Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, surrounded him in a barn, and killed him. Also on that day Jefferson Davis, still in Charlotte, North Carolina, learned that Confederate General Joseph Johnston had surrendered his army. It was now vital that Davis leave the state and cross the border into South Carolina.

Before Jefferson Davis left Charlotte, he wrote to General Wade Hampton: “If you think it better you can, with the approval of General Johnston, select now . . . the small body of men and join me at once.”

Then, in haste, Davis wrote a letter to Varina. “The Cavalry is now the last hope,” he told her. “I will organize what force of Cavalry can be had. [General] Hampton offers to lead them, and thinks he can force his way across the Mississippi. The route will be too rough and perilous for you and children to go with me. . . . Will try to see you soon.”

The funeral train left Albany at 4:00

P.M.

, Wednesday, April 26. Mile by mile, the crowds got thicker wherever the train was scheduled to pass. At Schenectady railroad signalmen waved small flags bordered with black. The train stopped briefly in Little Falls, where a band played a dirge while women presented flowers for the coffin.

At 11:15

P.M.

, the train made a short stop at Syracuse, where soldiers paid honors, a choir sang hymns, and a little girl handed a small bouquet to a congressman on the train. A note attached to the flowers read: “The last tribute from Mary Virginia Raynor, a little girl of three years of age.”

The train arrived in Rochester at 3:20

A.M.

on April 27, and the former president of the United States, Millard Fillmore, got on board for the next stop, Buffalo. Three and a half hours later, tolling bells and booming cannons awoke the citizens of Buffalo who had not already assembled at the railroad station. Abraham Lincoln had arrived.

At 8:00

A.M.

a procession, which included President Fillmore, went with the hearse to St. James Hall. Under a simple canopy of drooping black crepe, they laid the coffin on a platform while a musical group sang “Rest, Spirit, Rest.” Women from the Unitarian church placed an anchor of white camellias at the foot of the coffin. For more than ten hours, thousands of people, including many Canadians who had crossed the border for the occasion, viewed Lincoln’s body. It was during that day that Townsend and the others in Buffalo learned that John Wilkes Booth had been captured and killed.

* * *

As Lincoln’s train pulled out of Buffalo, Jefferson Davis spent the night at Yorkville, South Carolina. He was taking his time. His journey south was more like a farewell procession than a speedy flight.

On the night of April 27, General Wade Hampton wanted to lead his cavalry to the president’s side. But he was worried about what to do. His commander, General Johnston, had surrendered. This meant that Hampton was supposed to surrender, too. But he had already promised to come to Jefferson Davis’s aid. Whatever he did, he would risk dishonor. Hampton wrote a letter to General Johnston: “By your advice I went to consult with President Davis. . . . A plan was agreed on to enable him to leave the country. . . . On my return here I find myself not only powerless to assist him, but placed myself in a position of great delicacy. . . . If I do not accompany him I shall never cease to reproach myself, and if I go with him I may go under the ban of outlawry. I choose the latter, because I believe it to be my duty to do so. . . . I shall not ask a man to go with me. Should any join me, they will . . . like myself, [be] willing to sacrifice everything for the cause. . . .”

Other cavalry units also hoped to ride to Davis’s side, not to protect him, but to kill or capture him. Now that the manhunt for Booth had ended, Stanton could focus on Jefferson Davis. On Wednesday, April 27, one day after the actor was shot and killed, Stanton telegraphed an order to do whatever was necessary to capture the Confederate president and the gold he was rumored to be carrying. “[S]pare no exertion to stop Davis and his plunder. Push the enemy as hard as you can in every direction,” Stanton ordered.

Meanwhile, the funeral train rode on in the darkness of the night through New York State. “The night journey of the 27th and 28th was all through torches, bonfires, mourning drapery,

mottoes

, and solemn music,” Townsend remembered. At 12:10

A.M.

, Friday, April 28, the train passed through Dunkirk on the shore of Lake Erie. There, thirty-six young women, one for each state of the Union, appeared on the railway platform. Each was dressed in white, with a broad black scarf resting across one shoulder and holding in her right hand a national flag.

The train stopped at 1:00

A.M.

in Westfield. In 1861, when Lincoln had been on his way to Washington, he had stopped here to speak to Grace Bedell, a little girl who had written him a letter encouraging him to grow a beard. Now, four years later, a delegation of five women led by Grace’s mother, whose husband had been killed in the war, came aboard the train with a wreath of flowers and a cross. Sobbing, they approached Lincoln’s coffin and were allowed, as a special privilege, to touch and kiss it.

The train crossed the Pennsylvania state line and continued into Ohio.

On April 28 Davis and his entourage stopped at Broad River, South Carolina, to rest and eat lunch. They began talking of how the war had destroyed all that they owned. Most of their homes and property had been burned or taken by the Union armies.

Jefferson Davis was no exception. Two years ago, in 1863, an officer had brought word to Davis that his beloved plantation, Brier Field, would soon fall into the hands of Union soldiers. Friends urged Davis to order Confederate soldiers to rush to his plantation to rescue his slaves and other property and move them somewhere safe. Although he hated to lose Brier Field, Davis was outraged at the suggestion. “The President of the Confederacy cannot employ men to take care of his property,” he said. Later, when Union forces threatened his other house in Jackson, Mississippi, Davis again refused to send soldiers to protect his home.

On April 28 Varina Davis, then in Abbeville, replied to her husband’s most recent letter. He had accused himself of bringing her to ruin. She reminded him that she had never expected a life of privilege and ease. “You must remember that you did not invite me to a great Hero’s home, but to that of a plain farmer,” she told him. “I know there is a future for you.” But not, she thought, in South Carolina, Georgia, or Florida. Varina advised him to give up the cause east of the Mississippi River. “I have seen a great many men who have gone through [Abbeville]—not one has talked fight—A Stand cannot be made in this country.” She advised him to try to relocate the fighting west of the Mississippi.

Continuing on the road, Jefferson Davis gave away his last gold coin. John Reagan, the Confederate postmaster general, watched him do it. “On our way to Abbeville, South Carolina, President Davis and I . . . passed a cabin on the roadside, where a lady was standing in the door. He turned aside and requested a drink of water, which she brought. While he was drinking, a little baby hardly old enough to walk crawled down the steps. The lady asked whether this was not president Davis.” On hearing that he was, “she pointed to the little boy and said, ‘He is named for you.’ Mr. Davis took a gold coin from his pocket and asked her to keep it for his namesake. It was a foreign piece, and from its size I supposed it to be worth three or four dollars. As we rode off he told me that it was the last coin he had. . . .”

The president of the Confederacy was now penniless. Yes, he was traveling with half a million dollars in gold and silver, but that money belonged to the Confederate government, not its president. Davis would not use it for himself.

Now the only riches he possessed were the love and goodwill of the people. He hoped that, in the days ahead, as he pushed deeper into the South, the people there would show him better hospitality than he had received in Greensboro and Charlotte, North Carolina. His aides assured him that it would be so. In South Carolina and Georgia, they promised, the people still loved him and believed in the cause of the South.

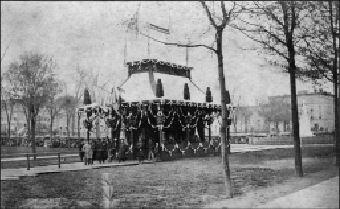

Lincoln’s train arrived at Cleveland on the morning of Friday, April 28. Thirty-six cannons fired a salute. There was not one public building or hall in all of Cleveland big enough to hold all the people who would want to view the president’s body, so the citizens built an outdoor pavilion. They could make it look like a Chinese pagoda. No one would forget

that.

The hearse took Lincoln’s coffin to the public square where the pagoda had been erected. The wooden structure, fourteen feet high, was covered with canvas, silk, cloth roses, golden eagles, and “immense plumes of black crepe.” Inside it was full of flowers. Evergreens covered the walls, and thick matting carpeted the floor to muffle the sound of footsteps. Over the roof, stretched between two flagpoles, was a streamer that read, in Latin, “Dead, he will be loved the same.”

The embalmer opened the coffin to check on the body. Lincoln’s face was turning darker by the day, which the embalmers tried to conceal by coating the skin with chalk-white potions.

All through the day and night, in a steady rain, the people came, one hundred thousand of them. The coffin was closed at 10:10

P.M.

and was carried to the hearse. Just then the rain turned into a downpour. The storm lasted for most of the night as the train steamed through Ohio from Cleveland to the state capital, Columbus.

In Cleveland, crowds wait to view Lincoln’s corpse in the celebrated “pagoda” pavilion.

The foul weather did not stop the people from turning out along the tracks. Bonfires and torches burned. Buildings were draped in black cloth. Bells tolled and flags were lowered to half-staff. Five miles from Columbus, the passengers on the train noticed a heartfelt tribute that stood out among all the official processions and ceremonies.

They saw “an aged woman bare headed . . . tears coming down her furrowed cheeks, holding in her right hand a sable scarf and in her left a bouquet of wild flowers, which she stretched imploringly toward the funeral car.” Her gesture was simple and touching. Abraham Lincoln would have noticed her. She might have reminded him of his stepmother, who had been waiting long years for him to return. “I knowed when he went away he’d never come back alive,” she had said when she’d heard of his murder.