Bloody Times (18 page)

Authors: James L. Swanson

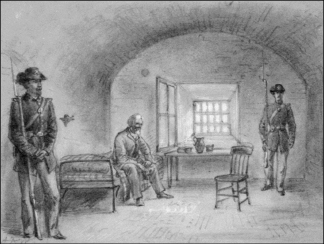

Printmakers continued to ridicule Davis after his imprisonment.

As Davis entered prison, Mary Lincoln at last moved out of the White House. Benjamin Brown French, the commissioner of public buildings and grounds, went to say good-bye. “Mrs. Mary Lincoln left the City on Monday evening at 6 o’clock, with her sons Robert & Tad (Thomas),” he wrote. “I went up and bade her good-by, and felt really very sad, although she has given me a world of trouble. I think the sudden and awful death of the President somewhat unhinged her mind, for at times she has exhibited all the symptoms of madness. . . . It is not proper that I should write down,

even here

, all I know! May God have her in his keeping, and make her a better woman. That is my sincere wish. . . .”

Contemporary sketch of Davis in his cell at Fortress Monroe.

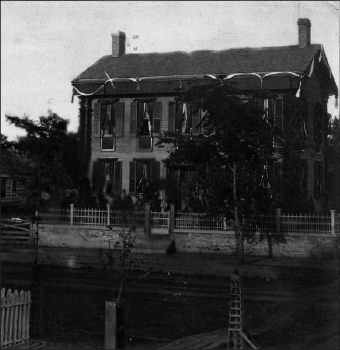

By May 24 Lincoln’s home in Springfield was no longer a center of the nation’s attention. But on this day a photographer—no one knows who—showed up to take the last known picture of the Lincoln home draped in mourning. The black bunting was windswept and weather-beaten. It was the same all across the nation. People could not bear to take down their wind-tattered, sun-faded, and rain-streaked decorations of death and mourning. Better, many thought, to allow time and nature to sweep them away.

After the funeral, the last photograph of Lincoln’s Springfield home draped in mourning, May 24, 1865.

On July 7, 1865, four of those who had helped John Wilkes Booth in his plot to murder Lincoln were executed. Three were sentenced to life in prison. But their trial had made one thing clear—Jefferson Davis had played no part in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. If Davis was to be put on trial or executed, it would be for treason, not for the president’s murder.

After several weeks of silence, Varina received her first letter from Davis since his capture. It was written on the twenty-first of August. “Kiss the Baby for me,” he wrote. “My dear Wife, equally the centre of my love and confidence, remember how good the Lord has always been to me, how often he has wonderfully preserved me, and put thy trust in Him.”

Davis and Varina wrote many letters to each other while he was in prison, and she was not the only person he received letters from. On January 29, 1866, a young girl in Richmond, Emily Jessie Morton, wrote to Davis to cheer him up.

“I hope that you will not think me a rude little girl to takeing the liberty of writing to you, but I want to tell you how much I love you, and how sorry I feel for you to be kept so long in Prison away from your dear little children. . . . I go to school to Mrs. Mumford where there are upwards of thirty scholars all of which love you very much and are taught to do so. When we go to Hollywood [cemetery] to decorate our dear soldiers graves on the 31st of May your little Joes grave will not be forgotten.”

On May 3, 1866, Varina Davis arrived at Fortress Monroe. She brought her baby daughter, Varina Anne, but left her other children behind. Her misson now was to save her husband’s life. Varina had been a popular and well-liked figure in Washington before the war. Now she used every social and political skill she had learned to save her husband. She wrote letters, met with important people, and talked to the newspapers. And eventually it began to work.

By the fall of 1866, the government had still not put Jefferson Davis on trial for treason. Davis welcomed the idea of a trial. If he was found innocent, then the South was not wrong—it did have the right to leave the Union. If he was found guilty, he was happy to suffer on behalf of his people. His death, he believed, would win mercy for the South.

The U.S. government wanted neither result. If a federal court said that it was

not

treason for some states to try to become a separate country, that would overturn the whole purpose and result of the war. But if Davis was found guilty and executed, he would become a martyr and inspire the South to fight back.

Davis stayed in prison through the winter of 1867. But by the spring the government finally decided that it wanted Davis off its hands. He would be released on bail. The government claimed the right to put him on trial at a later time, if they chose, but they would not do so now.

At 7:00

A.M.

on May 11, 1867, the former Confederate president, still a prisoner, left Fortress Monroe and boarded a steamboat for Richmond. At 6:00

P.M.

Davis reached the city, landing in the same place where, two years ago, Abraham Lincoln had received a wild welcome from the city’s slaves. Now the white citizens welcomed Davis back to his old capital. As he passed, men uncovered their heads and women waved handkerchiefs. “I feel like an unhappy ghost visiting this much beloved city,” Jefferson told Varina.

On May 13 Davis appeared in court, his supporters posted a bail of a hundred thousand dollars, and he was freed. He was never tried, never convicted of treason, or of any crime. Once free, his first act was one of remembrance. He brought flowers to the grave of his son Joseph Evan Davis at Hollywood Cemetery, and while there he also decorated graves of Confederate soldiers.

On June 1 a Confederate officer who had served under President Davis sent him a heartfelt letter, which rejoiced in Davis’s freedom. “Your release has lifted a load from my heart which I have not words to tell,” it said, “and my daily prayer to the great Ruler of the World, is that he may shield you from all future harm, guard you from all evil, and give you the peace which the world can not take away. That the rest of your days may be triumphantly happy, is the sincere and earnest wish of your most obedient faithful friend and servant.” The letter was signed by Robert E. Lee.

After his release, Davis was forced to ask himself questions. What did the future hold? Where would he go? What would he do? How would he live? How would he earn money? Like much of the South, his life was in ruins. He had lost everything. His plantation was wrecked, no crops grew there, and he owned no slaves to work the fields. Union soldiers had looted his Mississippi home of everything valuable. They even stole his love letters from Sarah Knox Taylor.

Davis also had to decide what

not

to do. He vowed to do nothing to bring dishonor upon himself, his people, or the Confederacy. Because so many Southerners were poor, he decided that he would not shame himself by accepting charity while others were in need. He would not speak publicly against the Union, out of fear that his words might cause his people to be punished. He would not run in any election. He knew without doubt that he could be elected to any position in the South. But to run he would have to take a loyalty oath to the Union, something he would never do. To swear that oath, to say secession was wrong, would betray every soldier who had laid down his life for the cause. He would rather suffer death. And lastly, he decided he would never return to Washington, D.C.

Oil portrait of Jefferson Davis as he appeared in the 1870s.

Davis tried a few jobs but did not have much success. He found his true calling in a new role: remembering and honoring the Confederacy and those who had died for its cause. He wrote articles and letters, answering countless questions about how the war had been fought. He read histories of the war written by generals and political leaders. He supported the creation of the Southern Historical Association.

During the years following his release from prison, Davis did not have a permanent place to live. In 1877 a friend invited Davis to visit her estate in Mississippi, Beauvoir, near Biloxi. When the owner died, she left the house to him in her will and it became his home. Davis seemed destined for a quiet life at Beauvoir: receiving guests, dining with friends, writing letters, and sitting on the veranda, enjoying the sea breezes. It was there that he finished writing a book about the Confederacy, which was published in 1881:

Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government.

On the front porch at Beauvoir.

Then an invitation came. In 1886 Jefferson Davis agreed to make a speaking tour, giving speeches in several cities in the South.

When he boarded the train, he could not have known that he would return from this trip a different man. He did not know that by the end of this journey, more than two decades after the end of the war, the South would love him more than it ever did.

On April 28 Davis, seventy-nine years old, arrived in Montgomery, Alabama. He had no idea what kind of reception he would receive. When he rose and began to speak, no one could hear him. The sound of thousands of cheering voices drowned him out. “Brethren,” Davis cried out. That single word—“brethren”—made the crowd shout even louder. Women stood on their chairs and, weeping and laughing from joy, flapped their handkerchiefs like little signal flags. Then the audience allowed him to speak.

Davis spoke of the war, of watching the young men of Alabama march bravely off to combat. “But they are not dead,” he told the crowd. “The spirit of Southern liberty is not dead. . . . I have been promised, my friends, that I should not be called upon to make a speech, and therefore I will only extend my heartfelt thanks. God bless you, one and all, men and boys, and the ladies above all others, who never faltered in our direst need.” His remarks done, Jefferson Davis sat down.

What happened next stunned the reporter from the

Atlanta Constitution

: “Such a cheer as followed the speaker to his seat cannot be described. It was from the heart. It was an outburst of nature. It was long continued. Mr. Davis got up again and bowed. . . . Men went wild for him; women were in ecstasy for him; children caught the spirit and waved their hands in the air.” Widows dressed in black collapsed at his feet. Confederate veterans, many missing arms or legs, and wearing their old uniforms, trembled at his touch.

Everywhere he went on his tour, he received the same kind of welcome. Southerners gathered along the tracks to watch his train fly by, just as Northerners had gathered more than twenty years before to watch for Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train. At every platform crowds thronged. Jefferson Davis was more popular than ever.