Boost Your Brain (28 page)

Authors: Majid Fotuhi

What they’re missing out on is more than just repair time for the body and brain. In recent years, we’ve begun to discover just how important sleep is for memory, learning, and behavior. Sleep, it turns out, helps us consolidate the information we receive while awake.

3

In particular, the slow brain wave activity of certain stages of sleep seems to aid in hippocampus-dependent memory of facts and information, while REM sleep may help us process procedural memory.

4

Fragmented or poor-quality sleep, then, may interrupt or hinder the consolidation of memories for long-term storage.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Blocking Airflow with Brain-Shrinking Results

Although a host of sleep disorders exist, there are two I see most often in patients with memory complaints: obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and insomnia.

We’ll start with OSA, a disorder that is associated with dropping oxygen levels during sleep, followed by daytime fatigue and sleepiness, or a sensation of “foggy brain.” One of the chief signs of OSA is heavy snoring, especially the kind that stops suddenly and is followed seconds later by a gasp for air. Those quiet moments are actually a dire sign: you’re not breathing. Hence the gasp for air. That’s not to say that all snoring is indicative of obstructive sleep apnea; some snoring is perfectly benign. OSA can be confirmed with a sleep study, which measures how many times per hour you experience a drop in your oxygen level. Fewer than five episodes per hour is acceptable, while fifteen episodes represent moderate sleep apnea, and more than fifteen represent severe OSA.

According to the American Sleep Apnea Association, some twenty-two million Americans suffer from OSA. But as many as 80 percent of OSA sufferers are undiagnosed.

5

And while it’s long been considered a men’s disease, we’re now learning that OSA in women has probably been vastly underestimated. In one study of four hundred women, 84 percent of obese women had OSA.

6

In fact, obesity is a major risk factor for OSA, in both men and women. In addition, having a large neck size—of more than seventeen inches in circumference for men or sixteen inches for women—increases your risk of OSA, as does having a small upper airway; a large tongue, tonsils, or uvula; a recessed chin, a small jaw, or a large overbite; and smoking or alcohol use. In addition, people over forty and African Americans, Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics are more likely to suffer from OSA.

The pauses in breathing caused by OSA can last from ten seconds to a full minute. Those lapses in breathing, of course, starve the brain of oxygen. Such oxygen restriction makes OSA, without question, one of the biggest brain shrinkers documented. In one study, patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea had brains with as much as 18 percent less grey matter than a control group.

8

I’ve seen time and time again how dramatic such a deficit can be. OSA patients feel forever tired, mentally foggy, and low on creativity. Plus they experience memory lapses that often send them my way in a desperate search for help. They may be irritable and even depressed as well.

Stop Bang: Do You Have Sleep Apnea?

In 2012, researchers at the University of Toronto reported a high degree of accuracy for this clever OSA screening mnemonic:

7

S

for

snore:

Do you snore loudly? Loud enough to be heard through closed doors?

T

for

tired:

Do you often feel tired during the day?

O

for

observed:

Has your snoring been observed by someone else, such as a spouse?

P

for

pressure:

Do you have high blood pressure?

B

for

BMI:

Do you have a body mass index greater than 35?

A

for

age:

Are you older than fifty?

N

for

neck size:

Do you have a neck circumference larger than seventeen inches for men or sixteen inches for women?

G

for

gender:

Are you male?

Answering yes to three or more of the above questions indicates a high risk for OSA.

Zapping Brain Growth

Why do my OSA patients have such trouble thinking? For starters, OSA starves the brain of oxygen, so much so that it raises the risk of strokes. Initially, sleep apnea can cause just small strokes, which may result in no major, noticeable problems, but they take their toll nonetheless. Such silent strokes, as you’ll read in

chapter 12

, may slow a sufferer’s thinking, cloud the memory, and even hinder the pace of walking or talking. In time, through its effect on the heart, on platelets in the blood, and on blood vessels, OSA can also contribute to major, disabling strokes.

In one study, presented at the American Stroke Association’s International Stroke Conference in 2012, researchers found that of the people they studied who had silent strokes, more than half also had OSA.

9

And an incredible 91 percent of patients who’d had a large stroke also had OSA. In the same study, patients with OSA also showed damage to their white matter areas, the brain’s network of highways.

This is due to the obvious effect that cutting off breathing has, but also to another factor that comes as a surprise to most of my patients. Sleep apnea causes blood platelets to become hypercoagulable, or more prone to clumping, which is one of the main reasons OSA contributes to an elevated risk of heart attack and stroke.

OSA is also associated with significantly low BDNF, as one study of twenty-eight men with OSA (compared to fourteen without) showed.

10

Being low on this brain fertilizer is a surefire way to miss out on brain growth and repair.

And OSA has a significant effect on brain wave activity. Often people with OSA have noticeable sleepiness during the day—a reflection of sluggish brain wave activity. A brain map EEG of an OSA patient, for example, would likely turn up too much slow theta activity, indicating the patient is far from the ideal alpha zone of the alert, calm, focused mind.

The end result is impaired function. In one telling study, Italian researchers followed a group of seventeen middle-age patients with severe OSA and fifteen volunteers without OSA, who acted as the control group.

11

All the study subjects took a working memory test and underwent MRI scanning, including functional MRI scans that looked at brain activity, at the beginning and end of the study.

Before treatment, “even if they were not aware of their cognitive deficits, OSA patients were impaired on most cognitive tests,” explains study author Vincenza Castronovo, a clinical psychologist and psychotherapist with the Sleep Disorders Center at Università Vita-Salute San Raffaele in Milan, Italy.

Functional MRI scans showed that when OSA patients performed a mental task, they “over-recruited” other brain regions in order to accomplish the task. In other words, they had to call on other parts of the brain in a sort of all-hands-on-deck surge of activity. “They were making more effort in order to perform,” says Castronovo of the OSA patients.

Those with OSA also had smaller hippocampi as well as reductions of grey matter volume in the frontal lobes and white matter damage.

The effects of such damage may be amplified as we age, even as early as midlife. When researchers at the University of California, San Diego, compared fMRIs and cognitive tests of young and middle-age volunteers with OSA to those of young and middle-age volunteers without OSA, they found patients under the age of forty-five who had OSA were able to compensate by recruiting other areas of the brain to maintain performance—the all-hands-on-deck phenomenon at work again.

13

But people in the forty-five- to fifty-nine-year-old age group who had OSA displayed reduced performance for immediate word recall and slower reaction times during sustained attention tasks, indicating they weren’t able to fully compensate. The researchers concluded that age combined with OSA offered a double insult—overwhelming the brain’s capacity to respond to daily cognitive challenges.

The Gender Gap: Women Take a Bigger Hit?

OSA is more common in men than it is in women, but there’s evidence that the damage done in women’s brains may be greater than in their male counterparts’.

One study by researchers at the UCLA School of Nursing—the same group that first linked OSA to damage in the brain about a decade ago—found that women with OSA have greater damage to their brains’ white matter, especially in areas of the brain important for mood regulation and decision making.

12

Women were more likely to be depressed as well (although I think it’s important to note that OSA can raise the risk of depression in men, too).

A Subtle Start

When OSA sufferers come to see me, they often complain about troublesome cognitive problems. They know something isn’t right; they just don’t know what, or why.

But, as Dr. Castronovo demonstrated, structural damage in the brain may be quietly unfolding long before an OSA sufferer realizes it. In one study, researchers examined the MRIs of OSA patients and noted reduced grey matter volume in several brain areas, including the hippocampus, despite the fact that the study’s sixteen participants performed fairly well on cognitive tests.

14

Eventually, with enough damage or with age, as noted above, their cognitive scores would likely decline.

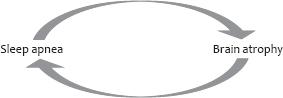

Not only that, but their OSA would probably get worse. Why? The damage done by OSA can affect the area of the brain responsible for controlling breathing during sleep, increasing the severity of sleep apnea. As with many other brain shrinkers, it’s a vicious cycle—the more you have sleep apnea the worse it may get.

Getting treatment sooner rather than later, then, is obviously the best bet. That advice is all the more compelling when you consider that damage from OSA to the brain’s blood vessels may be measurable in mere weeks. In one animal model, for example, blood flow was restricted after just one month of OSA, a finding that is consistent with the reduced blood flow and oxygenation we see in patients with sleep apnea.

15

Insomnia: Shorting Your Brain on Sleep

In the winter of 2012 I began treating a patient, Gregory, who you might call a little type A. Gregory, a lawyer, habitually slept just four hours a night, dozing off at midnight and waking at four in the morning, without really even meaning to. Once awake, he’d fill the time with work. “It’s not a problem,” the fifty-year-old told me. “I’m used to it.”

Except, it

was

a problem. Gregory had made an appointment to see me because he’d increasingly been experiencing memory lapses. They were the types of slips any busy person can relate to. Engrossed in work, he might forget to meet his wife for dinner. Or misplace a file. Or realize—while zipping down the highway—that he’d left his coffee cup on the car roof. It can happen to anyone. But lately it had been happening to Gregory quite a lot.

Like many people who have memory lapses, Gregory couldn’t quite shake the fear that he was beginning to show the signs of Alzheimer’s disease. After I completed my full evaluation, I was happy to tell him that his fear was unfounded. But that didn’t mean he was off the hook. Gregory’s lifestyle, I explained, was unquestionably shrinking his brain.

Like many insomnia sufferers, he had never talked to a doctor about his early-morning awakening, considering it just a quirk that he had to live with. Had he known the damage he was doing to his brain, though, he might not have been quite so cavalier.

First, a little about the condition, which is one of interrupted or inadequate sleep. Insomnia is defined by a difficulty to initiate or maintain sleep for at least one week. If you suffer from insomnia, you may have trouble falling asleep, may fall asleep but awaken at night and have trouble getting back to sleep, may awaken very early or wake up not feeling refreshed. Whatever the case, you’re not getting long stretches of uninterrupted sleep, which means you’re not benefiting from a good night’s slumber.

Insomnia is often related to or associated with another problem, either physical or psychological. Stress, depression, medications, caffeine, alcohol, shift work, chronic pain, or health problems (such as the hormonal fluctuations of menopause or restless leg syndrome, which could be due in part to iron-deficiency anemia) all can cause insufficient restful sleep. Often insomnia results in irritability and difficulty with attention, memory, and concentration.