Boost Your Brain (31 page)

Authors: Majid Fotuhi

• women;

• blacks, Hispanics, persons of other non-Caucasian races or of multiple races;

• people with less than a high school education;

• people who have been previously married;

• unable to work or currently unemployed; and/or

• without health insurance coverage.

That size difference doesn’t tell us which came first, of course. We don’t know for sure whether depression shrinks the hippocampus or whether people with smaller hippocampi are more prone to depression. One MRI study of children with a family history of depression found that the children had smaller hippocampi even before they showed any signs of depression.

11

Other studies, however, show conflicting evidence.

It’s quite possible, given the contradictory evidence, that the answer to the question might be both: depression shrinks the hippocampus and a smaller hippocampus makes people more prone to depression. We do know, however, that depression is linked with lower BDNF, which may explain that smaller hippocampal size.

12

And while no study I know of has found that depression

causes

reduced blood flow to the brain, the symptoms of depression—like feeling blue or lacking an interest in life—may involve sluggish blood flow to the brain. This is exactly what one study showed.

13

Researchers at the Royal Free Hospital’s School of Medicine in London used PET scans to measure blood flow in thirty-three patients with known depression. They found that melancholic patients had reduced cerebral blood flow in the prefrontal and limbic areas. Other studies have found significant decreases in blood flow to the prefrontal cortex.

14

Depression also, not surprisingly, puts a serious damper on healthy brain activity. The EEG brain map of a melancholic depressed patient, for example, might show too much slow theta activity on one side of the brain. If you imagine the brain as an orchestra, you can think of this orchestra being comprised of a collection of tubas producing mostly low and slow sounds. A person with an anxious type of depression, on the other hand, might produce a map showing too much high beta, particularly on the right side of the brain. The anxious person’s orchestra would be made up primarily of violins playing screechy high notes.

Both maps represent brain activity that’s far from the calm, focused alpha zone we know to be vital for a strong brain. It’s no surprise, then, that depressed patients report being forgetful, unable to pay attention, and lacking in clarity and creativity.

Depression is also interlinked with other brain shrinkers, such as obesity and insomnia. The upside of that connection is that treating one condition may help improve the others.

Reversing the Effects

Stress is so pervasive, and the harmful effects on the brain so profound, that I believe treating and preventing it should be considered a national priority. And I’m not alone in thinking that. My friend and colleague, Cleveland Clinic preventive medicine professor Dr. Michael Roizen, views stress management as more critical even than stopping smoking. Dr. Roizen is a co-author of the YOU series with Dr. Oz, and knowing all the different factors that affect our bodies and minds, he puts stress reduction at the top of his list of priorities for improving public health and reducing the burden of diseases in our country.

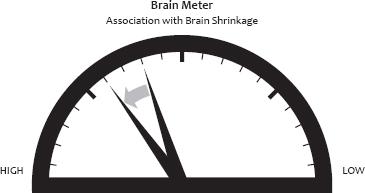

Chronic and excessive stress, especially when combined with major depression, insomnia, or high blood pressure, is associated with brain atrophy. The worse the symptoms and the longer they persist, the more your brain will shrink.

Extreme Stress: PTSD

At the extreme end of the stress spectrum is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), an anxiety disorder that occurs when someone is exposed to a highly stressful event. People can suffer PTSD even if they aren’t physically harmed by the event or are only a witness to the event.

Sufferers of PTSD experience an array of psychological problems, from persistent anxiety and vivid memories of the traumatic event, to avoidance of anything that reminds them of the event, to sleep problems and an inability to stop thinking about the event. Sufferers might also become emotionally detached, numb, or even self-destructive.

Scientists are still trying to understand exactly what happens in the brain to cause PTSD. Why do some develop it and others do not? We still don’t know. But we do know that people with PTSD have smaller hippocampi.

One possible explanation for this is that people who develop PTSD actually had smaller hippocampi to begin with. In one study of identical twins, for example, researchers found smaller hippocampi in people who’d been in combat and suffered PTSD

and

in their identical twins, who hadn’t been in combat and didn’t have PTSD.

15

That finding seems to suggest that having a smaller hippocampus may predispose a person to developing PTSD if that person is exposed to a traumatic event. However, more research needs to be done to better understand PTSD.

Fortunately, stress management is entirely doable and depression is treatable in most people. Even better, when it comes to the damage wrought by chronic stress, the effects do seem to be reversible.

In the case of Dr. McEwen’s medical students, for example, one month after they’d taken their exams, connectivity problems in the brains of formerly stressed students had disappeared. “So, in these young human subjects these kinds of effects of everyday experiences of feeling out of control of your life actually can have reversible impairments that you can recover from by taking a vacation,” says Dr. McEwen.

Even the brain shrinkage associated with depression can be largely reversed with medical therapy. Many studies, for example, have shown that the hippocampus begins to grow again after treatment of depression. Antidepressant medications, in particular, have been tied to such changes. One study of twenty-four patients with major depressive disorders, for example, found that depressed people treated with antidepressants had increased angiogenesis as well as increased neurogenesis in their hippocampi, compared to untreated depressed patients.

16

The Aging Brain

The research on the reversibility of brain changes caused by stress is encouraging. But before you heave a sigh of relief, you should know that older brains might not recover from brain changes quite as easily as younger brains. Older animals, for example, show the same response to stress as younger animals, but their brains don’t “bounce back” after a stress-free recovery period in the way that younger brains do, says Dr. McEwen. This may be a matter of brain reserve—after a lifetime of wear and tear, an older person has less of a buffer zone to work with. An insult that might barely make a dent on a younger person’s brain might tip an older counterpart closer to cognitive decline.

Certainly, the damage done by stress and depression appears to increase the risk of dementia later in life. Both shrink the hippocampus. And one study found depressed people over the age of 65 experienced 24 percent greater annual cognitive decline than their non-depressed peers.

17

There is evidence, too, that stress may contribute to the risk of developing vascular dementia, a type of dementia caused primarily by small and large strokes. In a 2011 study, researchers evaluated 257 demented people and more than 9,000 non-demented people who’d taken part in the Study of Dementia in Swedish Twins.

18

They found that having a stressful job with low control, along with low social support, increased the risk of developing dementia, particularly vascular dementia. This is most likely related to the link between high stress and high cortisol, leading to high blood pressure and stroke. Making changes in the workplace so that employees feel they play a more meaningful role might help to lower that risk, the study authors suggested.

Laughter as Medicine?

As a medical intern assigned for two months to the coronary care unit at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in the 1990s, I quickly became accustomed to patients who weren’t in tip-top shape. After all, most of the patients there had suffered heart attacks and were in the early stages of recovery. But there was something that stood out in my mind about the heart disease patients I encountered: they were very often, although not always, overly tense individuals. These were hard-charging executives, lawyers, and others who worked long days, which left them little time for fun. And they were, well, grumpy. Grumpier than any other group of patients I came across, quite honestly, even in the oncology, surgical, or gastrointestinal units. Were they unhappy because they were in the hospital, or were they in the hospital because they were unhappy?

I’ll never know the answer, but those patients always pop into my mind when I talk to my own patients about the importance of living a balanced life and the value of laughter and happiness—even with a busy schedule.

Science backs me up on this. In 2001, researchers at the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC) reported their study on the benefits of laughter in heart health.

19

For the study, the team used questionnaires to gauge how prone to laughter three hundred volunteers were. Tallying the results, the research team found that those who’d suffered a heart attack or undergone coronary artery bypass surgery responded with less humor to everyday problems compared with those who had normal heart health.

Could being good-humored actually improve heart health? The study didn’t preclude the possibility that heart problems might make people less likely to laugh (rather than less laughter contributing to heart disease), so the research team, led by the director of UMMC’s Center for Preventive Cardiology, Dr. Michael Miller, tried another angle.

This time they studied twenty volunteers in good cardiovascular health, measuring the flow of blood through the arteries of their upper arms at baseline and then again just after watching a funny movie clip and just after watching a violent movie clip.

20

They found that laughter appeared to increase blood flow. The violent movie clip, on the other hand, caused volunteers’ blood vessels to constrict, reducing blood flow.

Just why that happened isn’t yet clear. But other studies have given more cause to engage in a hearty chuckle. Some have found that laughter reduces the level of cortisol and boosts our immune systems.

21

That’s not to say you need to laugh constantly; what’s important is maintaining a happy mood and a good sense of humor.

Getting Better

There are countless strategies for reducing stress in our lives, as a quick glance at any of the many health magazines on newsstands bears out. I often find that the biggest obstacle for my patients isn’t learning what to do; it’s acknowledging they have a problem to begin with. Many simply don’t believe their stress level is harming their brains.

They have me as their doctor, though, and I usually convince them rather quickly of the importance of stress reduction as well as the treatment of depression. If you suspect stress or depression may be an issue for you and you’re not already talking to your doctor about it, you should do so immediately. This is especially important in the case of depression, since depression symptoms can actually be caused by health problems, such as low levels of B12, thyroid problems, anemia, sleep apnea, and silent strokes, among other things. Certain medications, especially pain medications, can also contribute to a depressed mood.

At my Brain Center, although I do prescribe antidepressants when needed, I also focus on eliminating symptoms through other measures. One is sleep improvement. Often depression goes hand in hand with sleep disorders, so I work both angles to try to reduce the symptoms of each. Another is exercise, which has been shown to be incredibly effective—some suggest as effective as antidepressants—in ameliorating the symptoms of depression. Often my patients have to start slowly with exercise. Depression affects their energy level, so even something as seemingly simple as a five-minute walk may be overwhelming for them. I have them start small and then work their way up to longer, more rigorous exercise as their depression symptoms improve. You already know exercise’s brain-boosting potential, so you won’t be surprised to hear that, often, the more they exercise the better they feel.