Boost Your Brain (32 page)

Authors: Majid Fotuhi

To help reduce stress and anxiety, my patients also use a combined meditation–cognitive behavioral therapy approach that I described in

chapter 6

. Using the ABC method, they try to change the way they view and respond to stressors in their lives—and improve their mood and attitude as a result.

And while no supplement has been shown to treat depression, healthy eating has clear brain benefits, so I prescribe for all my stressed and depressed patients the dietary changes you read about in chapter 5. Exercise and dietary changes have many other benefits, including helping to reduce the risk of obesity.

Patients enrolled in my brain fitness program also undergo neurofeedback and cognitive training to help promote healthy brain activity and improve their attention, focus, and problem-solving abilities. Last but certainly not least, I strongly recommend that all my patients find natural ways to boost their mood every day. Whether that’s finding a favorite go-to website that’s guaranteed to give them a chuckle, having a smile-inducing photo album handy, or finding some other form of instant cheer, laughter is good for heart health, which of course benefits the brain.

Y

OU PROBABLY

won’t be surprised to hear that I’m fairly careful about eating, exercising, and maintaining a healthy weight. I have, after all, spent the past twenty years studying the effects of such things on the brain, and what I’ve learned has shaped my behavior. But I wasn’t always health conscious.

In fact, as a medical intern I developed a set of lifestyle habits that left me, for a short while, with a bit of blubber around the belly. Most weeks I clocked more than a hundred hours of work in a high-stress environment, leaving me little time for exercise, a full night’s sleep, or a healthy meal. Often I’d eat whatever was handiest—a slice of pizza, a cafeteria cheeseburger, a bag of chips—in between treating critically ill patients. And though I’d never been a junk food junkie, I suddenly found myself craving sugary treats like soda or donuts, the effects of which translated to an expanding waistline.

I eventually moved on to become a resident in neurology, working a more reasonable schedule. But had I kept up those habits long enough, I have no doubt that I would have piled on more pounds. Longer still and I would have likely developed elevated blood sugar, high blood pressure, perhaps even diabetes.

They’re the same problems I encounter today in many of my patients, who are among the 68 percent of American adults who are overweight or obese. But they almost never come to see me

because

of their weight. Instead, they walk through my door in search of solutions for their memory lapses or foggy thinking. They have no idea that their bulging abdomens are almost certainly shrinking their brains, directly and indirectly. And they don’t know that their high-fat, high-sugar diets have changed their brains in ways that make them less likely to make good food choices in the future.

My patients are almost always stunned when I explain the link between excess weight and a shrinking brain. And they’re usually eager to get started reversing the damage. I have a program to help them do just that, but first I explain for them exactly how extra pounds—and their food choices—reshape their CogniCity.

Excess Weight, from Bad to Worse

Often when scientists talk about the dangers of being overweight they focus first on the obese. That’s understandable. The effects of excess weight tend to be most dramatic in the obese, whose body mass index (or BMI, a measurement of weight as it relates to height) is 30 or above.

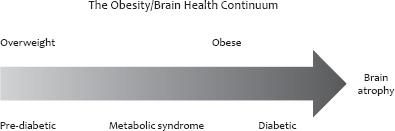

But while being obese may be very bad, being merely overweight (with a BMI of 25 to 29.9) isn’t good either. As you’ll soon read, excess weight takes a toll on memory and cognitive function and also raises the risk of developing pre-diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes, all of which carry you further along the brain-shrinking continuum. And while weight doesn’t solely determine your likelihood of developing these conditions, generally speaking, the more you weigh the greater your risk. Here’s a quick look at each:

Pre-diabetes,

or impaired glucose tolerance, occurs when blood sugar is high but not high enough to meet the threshold for diabetes. It is often the first hint of increased glucose intolerance—a sign that your body is becoming unable to regulate glucose levels in the blood—and it affects an estimated seventy-nine million Americans, according to the American Diabetes Association.

Metabolic syndrome

is defined by the International Diabetes Federation as a combination of central obesity (abdominal fat) and two or more of the following: a triglyceride level of more than 150 mg/dL; an HDL level of less than 40 mg/dL (or less than 50 mg/dL in women); a blood pressure of 130 over 85 or more or previously diagnosed hypertension; or a fasting glucose level of more than 100 mg/dL or previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Metabolic syndrome raises your risk of developing coronary artery disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes.

Type 2 diabetes

is a condition in which the body either doesn’t produce enough insulin—the hormone that helps regulate blood sugar levels—or the body’s cells have become resistant to insulin. Either way, the result is elevated blood sugar levels that cause damage to blood vessels. Type 2 diabetes is usually diagnosed in adults. Some 25.8 million Americans, or 8.3 percent of the population, suffer from the disease today. For simplicity, when I refer to diabetes, you can assume I’m talking about type 2 rather than type 1 diabetes, which is a condition usually diagnosed in childhood and in which the body produces no insulin. Diabetes and excess weight can occur independent of each other: you can be diabetic but not overweight or overweight but not diabetic.

Although it’s treatable, diabetes can contribute to the development of a variety of serious health problems, including heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, high blood pressure, nerve damage, and blindness. Each of these conditions contributes to brain atrophy, with effects on brain function that range from subtle to severe.

What’s Going On Under the Skull

Just how excess weight, obesity, and diabetes affect the brain is still an area of intense research. But we’re gathering more pieces of the puzzle every day.

For starters, we know that obesity is tied to low BDNF, the brain-healing, neuron-fertilizing protein we need for a strong brain. In one study of seventy-three obese children and forty-seven non-obese children between the ages of seven and nine, BDNF tended to be lower in obese children compared to their leaner peers. What’s more, after two years those who had lost weight, practiced sports, and had a low-carb diet saw an increase in their levels of BDNF.

1

In another study, researchers in Denmark measured BDNF levels in obese and non-obese men and women with and without diabetes.

2

People with diabetes had lower levels of BDNF regardless of their weight, suggesting that diabetes may have its own effect on BDNF.

Perhaps the more obvious mechanism of brain shrinkage, though, is the reduced blood flow to the brain that accompanies excess weight, pre-diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes. Metabolic syndrome, for example, may be associated with a reduction in blood flow to the brain of up to 15 percent.

3

That’s an alarmingly high number—remember, neurons need oxygen to stay healthy, as do the helper cells that maintain the brain’s highways.

Excess weight also contributes to the risk of developing vascular problems, such as high cholesterol and high blood pressure, and ultimately raises the risk of stroke. Generally speaking, the more excess weight you carry, the greater your risk.

And excess weight contributes to the risk of OSA, another condition of oxygen starvation. Excess pounds also very often (though not always) limit a person’s mobility, sometimes drastically. That lack of exertion lowers blood flow to the brain and robs a person’s brain of oxygen and nutrients.

In addition, the elevated cortisol levels associated with being overweight or obese may damage the brain. Elevated cortisol not only causes the structural changes you read about in

chapter 10

but also increases unhealthy brain wave activity. Patients with obesity and high cortisol tend to have too much fast beta activity in the brain and too little of the alpha activity that’s associated with a focused, calm, and alert brain. Conversely, the blood flow problems associated with excess weight, obesity, and diabetes can also result in slower activity in parts of the brain. For example, “dead zones” in the frontal lobes caused by major, small, and micro strokes have low or no activity, leading to sluggish thinking. To go back to our brain orchestra, you can imagine a row of tubas in front pumping out slow, low notes, while elsewhere in the pit dozens of violins briskly hit high notes, thanks to excess cortisol.

Scientists still aren’t certain about exactly how diabetes does its damage in the brain, although it’s clear that high blood sugar contributes to atherosclerosis, which contributes to vascular dementia (caused by strokes of different sizes). It’s likely that other elements are at play, too. Insulin resistance may interfere with the ability to break down amyloid plaques—one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease—in the brain, for example. High blood sugar, meanwhile, may contribute to oxidative stress, which damages cells in the hippocampus. Excess cortisol, high levels of insulin in the blood, and inflammation likely combine to make their mark on brain cells, too.

A Crumbling CogniCity

As you know by now, low BDNF, poor oxygen flow, and unhealthy brain activity harm the brain. Excess weight, obesity, and diabetes, in other words, destroy synapses, wither blood vessels, batter highways, and kill neurons.

The result, of course, is a smaller brain, as researchers at the University of Pittsburgh demonstrated in 2010—8 percent smaller, in the case of the obese people they studied.

4

The study subjects were ninety-four elderly men and women enrolled in the Cardiovascular Health Cognition Study, all of whom showed no outward symptoms of dementia or Alzheimer’s disease. Using a novel method to create 3-D maps of brain atrophy, the research team showed that having a BMI greater than 30 carried with it the most dramatic effect: significant decreases in the volume of grey matter. But even being merely overweight (with a BMI of 25 to 29.9), rather than obese, resulted in white matter atrophy.

In obese people, the loss of brain volume appeared to most affect certain parts of the brain: the frontal (attention) and temporal lobes (language), the hippocampus (memory), and the anterior cingulate gyrus (mood), for example. The result of such atrophy is foggy thinking, fatigue, poor memory, and irritability.

The relationship between global brain volume (the size of your brain) and BMI is linear, which means any excess body weight is associated with a slight reduction in brain volume, as one study of 114 individuals forty to sixty-six years of age showed.

5

There’s no upper cutoff, so a BMI of 40 is worse than a BMI of 35, which is worse than a BMI of 30.

It’s important to note that there is a lower cutoff: being excessively underweight is also associated with a smaller brain. In one study, researchers found that patients with anorexia nervosa had reduced brain volumes.

6

Those who gained weight after recovering from anorexia, however, showed a rebound in their grey and white matter volumes.

Abdominal fat appears particularly suited to shrinking the brain, as Dr. Stephanie Debette and her colleagues at Boston University found when they studied the MRIs of 733 participants enrolled in the Framingham Heart Study.

7

Initiated in 1948 to study factors that cause cardiovascular disease, the Framingham Heart Study started with about 5,200 volunteers aged thirty to sixty-two living in Framingham, Massachusetts, a town set just a thirty-minute drive to the west of Boston. Over the years, the study has ballooned with so-called cohort studies of the children and grandchildren of the original participants. Researchers have followed the participants and their cohorts closely, tracking their physical health and interviewing them at length about their lifestyles. As you can imagine, given its size and scope, the study has been a gold mine of information for experts examining a host of health problems. In fact, the study has spawned more than 1,200 articles in medical journals.

Dr. Debette’s was one such study. Participants were cognitively healthy and relatively young, with an average age of sixty years old, but those who had a higher BMI, a larger waist circumference, greater abdominal fat, and a bigger waist-to-hip ratio were more likely to have lower brain volume. Abdominal fat seemed to show the strongest link with reduced total brain volume, while waist-to-hip ratio was associated with more specific reduced volume in the hippocampus.