Boost Your Brain (36 page)

Authors: Majid Fotuhi

To determine patients’ fitness levels we measure VO

2

max by having them exercise strenuously on a stationary bike. They then meet with our exercise physiologist and start a personalized program of diet and exercise to boost their fitness by 5 percent every five weeks. We also teach them about heart-healthy food, as well as foods that are particularly effective at reducing the risk of stroke and boosting brain growth (see

chapter 5

).

One such food is chocolate, which was shown to reduce the risk of stroke in a ten-year study of Swedish men. In that study, researchers found that when they adjusted for all other factors, consuming a third of a cup of chocolate—or 63 grams per week—reduced the risk of stroke by about 17 percent.

14

Remember Marc, my stroke patient? Before I’d explained to him all that you’ve just read, I’m not sure he really would have committed to changing his life. After all, he had put off exercising—and even sleep!—for years, with the lament “I just don’t have time!” I’m sympathetic. Everyone, myself included, feels short on time at some point in his or her life.

After an hour with me, though, Marc understood that he was on a path toward increasingly noticeable cognitive difficulty at best, and a massive stroke or death at worst. Suddenly, finding time seemed the least of his problems.

Marc cut back on work, started weekly meditation sessions, and shifted his outlook from one that screamed “live to work” to one that calmly (and happily) declared “work to live.” He lowered his cholesterol and his blood pressure. With vigorous exercise, his exercise capacity (measured by VO

2

max) increased by 15 percent in three months. Since his sleep apnea was merely borderline, we opted to treat it with weight loss, which was successful.

True to form, Marc tackled his brain fitness efforts just as he would have approached any venture: with determination and grit. Within months he was fit, strong, and feeling mentally sharper. He had reduced his future risk of stroke and no doubt had grown his brain in the process.

B

Y ALL ACCOUNTS

, my patient Gary had some spectacularly bad luck throughout his life. It started with a particularly gruesome accident when he was just a child. Riding in the back of a pickup truck, he not only fell out but also somehow became trapped and was dragged behind the truck. Among his injuries was a fractured skull, a traumatic brain injury (TBI) that left him unconscious for four days. Fortunately, he went on to make what seemed to be a full recovery over the next five years.

As an adult, though, he was in for more bad luck. Mouthing off at the wrong moment, Gary, a mechanic from Delaware, found himself in a fight outside a bar one night. The scuffle ended with him taking a hard hit to the head from a baseball bat, an injury that left him blind in one eye. A decade later, he was hit by a truck while walking along a busy road at night. Then, in his sixties, he contracted pneumonia and became critically ill. During his illness, he experienced serious cognitive problems; at his worst, he was so confused that he failed to recognize even his son. Thankfully, Gary recovered, yet again. But many of his cognitive deficits persisted.

When he came to see me, Gary, then sixty-nine, was experiencing profound memory and thinking problems. His son, who accompanied him on his visit, told me Gary had never truly bounced back from pneumonia. “I think he’s about 30 percent of what he used to be,” Gary’s son said, shaking his head.

And no wonder: Gary’s MRI showed brain atrophy and extensive white matter damage. His EEG brain map, meanwhile, painted a picture of sluggish brain activity, with excess slow theta waves in his frontal lobes. And Gary’s cognitive testing results reflected his brain’s poor function: his memory and other cognitive skills were far below average for his age and education level.

His pneumonia had actually been the final straw for a brain that was no doubt low on reserve, thanks to the battering it had taken over the years, starting with that first fall off a truck. In fact, the damage done by that injury no doubt contributed to his likelihood of encountering his future injuries. Reduced function in his prefrontal cortex—which you’ll remember is the brain’s braking system—was likely a factor in Gary’s behavior outside the bar that night, which earned him a crack across the head, further injuring his brain.

That

TBI may have further affected his future ability to make smart decisions, like whether or not to walk alongside a busy road at night, setting him up for his third injury.

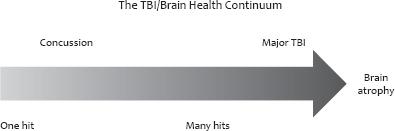

Gary’s story was fairly dramatic, I’ll admit. But every week I see patients who have similar, albeit less extreme, effects from concussions and serious TBIs. Fortunately, neuroscientists have learned a great deal in the past decade about just what happens in the brain when it’s injured by trauma, information that has vastly advanced the treatment of concussions and serious TBIs. One of the more important discoveries was proof that, while a major TBI is clearly terribly damaging to the brain, small concussions can cause lasting injury, and multiple small injuries can add up over time.

What Is a TBI?

The term “traumatic brain injury” sounds like something you’d only hear in a hospital emergency room, but TBI is actually becoming an increasingly familiar term in discussions about sports, car accidents, and battlefield injuries. An umbrella term that includes injuries ranging in severity, a TBI is any type of brain injury that results from a blow to the head or a severe shake or jolt that damages the brain. It can be a closed injury, in which there is no penetration into the skull (as you might have if you fell off a motorcycle), or a penetrating injury, in which an object pierces the skull (as would happen with a gunshot to the head).

Each year an estimated 1.7 million people in the United States suffer from a TBI of some sort, according to the Centers for Disease Control. (Some estimates are even higher.) Thankfully, the vast majority of sufferers—about 75 percent—have a mild form of TBI: a concussion. The term “concussion” is often used interchangeably with the term “mild TBI” (and I’ll do the same here).

Immediate signs of a concussion, according to the American Academy of Neurology, may include:

• a vacant stare,

• delayed verbal and motor responses,

• confusion or an inability to focus attention,

• disorientation,

• slurred or incoherent speech,

• stumbling or an inability to walk a straight line,

• emotions out of proportion with circumstances, and/or

• memory deficits.

Symptoms, often called “post-concussive syndrome,” can appear immediately or within days of the injury. They include:

• headaches,

• changes in vision (including blurring, “seeing stars,” or double vision),

• short-term memory loss,

• difficulty concentrating,

• nausea,

• vomiting,

• dizziness or balance problems,

• ringing in the ears,

• sensitivity to light or sound,

• changes in taste or smell,

• mood swings,

• sleep changes (too much or too little),

• depression, and/or

• fatigue.

Symptoms of more serious TBIs can appear immediately or within days of the injury and include:

• confusion,

• coordination problems,

• agitation or aggression,

• difficulty with language,

• weakness or numbness in the extremities,

• loss of bladder or bowel control,

• severe headache,

• repeated vomiting,

• dilation of one or both pupils,

• clear fluids draining from the nose or ears,

• convulsions or seizures, and/or

• loss of consciousness.

For most people, a mild concussion will resolve in a week to ten days with minimal treatment, which might include cognitive and physical rest, plus pain killers to treat headaches. But concussions can be deceptive: seemingly small injuries can produce lasting deficits.

What Happens in the Brain

If you had looked inside Gary’s brain after any one of his TBIs you would have witnessed a devastating cascade of events unfolding in the minutes, days, and weeks following the initial injury. For starters, the brain, you’ll recall, is a Jell-O–like bundle suspended inside a bone cage. If the outside of that cage—the skull—is met with force, the contents inside shift, often quickly and with force. So, the initial blow to Gary’s head would have caused a “brain bruise”—a contusion at the point of contact called a coup—as it slammed into his skull. He might have also suffered a second brain bruise—called a contrecoup—in the part of his brain opposite the initial point of contact, as his brain rebounded from its initial hit and collided with the skull yet again. Often such injuries occur at the “tips” of the frontal and the temporal lobes, since these brain areas are closest to the skull. Severe TBIs lead to major brain bruising and swelling, which can cause further injury.

Many TBIs also cause “shear” or “diffuse axonal” injuries, in which the brain is subjected to a twisting motion inside the skull. As a result, the fiber bundles that carry signals across the brain are damaged. These are the brain’s highways and, remember, they’re not made of asphalt. In fact, they’re more like a delicate collection of strands, each a thousand times thinner than the width of a human hair. It doesn’t take an event as severe as Gary’s baseball bat to the head to cause such an injury. Such damage can be done even when there is no direct contact at all, which might happen in a whiplash injury, for example. Shearing can happen with or without a brain bruise and can be either microscopic or large enough to be seen on MRI. Just as a silent stroke might go unnoticed, a small tear in a fiber bundle might cause no apparent symptoms, while a larger shear injury likely would produce noticeable issues. Depending on which part of the brain was damaged, cognitive problems that result might include not being able to calculate a tip in a restaurant, having difficulty finding your way in a familiar neighborhood, or struggling to complete a crossword puzzle, among many other possibilities.

Whether it’s a contusion or a shear injury, if we zoomed in on neurons in the affected brain areas, we’d see injured mitochondria. These mitochondria would be unable to properly do their job, part of which is generating the energy needed for regulating the release of glutamate, an excitatory messenger molecule in the brain. With too much glutamate, affected neurons would be excited to death—a phenomenon called excitotoxicity. The more glutamate, the more damage.

Three Phases of TBI

INITIAL INJURY

:

Coup, contrecoup, and shearing.

SECONDARY INJURY

: Inflammation and restricted blood flow.

REPAIR

: Increased BDNF, synaptogenesis, and fiber sprouting.

The chain reaction caused by the TBI would continue as the brain’s defense system leaped into action, sending specialized inflammatory cells to clean up damaged neurons. Unfortunately, while these cells do help, they also cause collateral damage when their cleaning efforts spill over to engulf healthy bystander neurons.

Collateral damage also includes injury to the blood vessel linings—called the blood–brain barrier—and allows chemicals to enter the brain.

1

This escalates inflammation, which then results in further damage to blood vessels and therefore reduced blood flow to the brain. As with glutamate, more inflammation means more damage. And it comes at the very time the brain needs optimal blood flow to fuel the healing process. The reduced blood flow—or ischemia—that results from such inflammation can continue to worsen over several days after the initial injury and can last for months.

2

At the same time that the brain is fighting to limit damage, meanwhile, it is also beginning to repair itself. Immediately following an injury, production of the healing and building protein BDNF ramps up. Oftentimes, synaptogenesis increases and new dendrites sprout in the neurons of the injured brain.