Boost Your Brain (39 page)

Authors: Majid Fotuhi

In addition, alcohol abuse damages myelin, the protective coating that covers neuron extensions. This causes neuropathy, or nerve damage, in the nerves leading from the spine to the feet. With their brains not getting good sensory signals from their feet, alcohol abusers suffer from poor proprioception—the body’s sense of where its parts are in space. That combined with damage to the cerebellum leads to balance problems and difficulty walking. Lara’s trouble walking was the early manifestation of this combination of factors. She did not yet experience falls, but in severe alcoholics such damage can cause frequent stumbling, particularly on stairs or curbs.

The brain of an alcohol abuser also suffers in another way: from the absence of key nutrients like thiamine, folate, and B12, caused by a poor diet. These nutrients are vital to overall brain function, and people who abuse alcohol often have dietary habits (beer and chips, anyone?) that deprive their brains of these important building blocks. Through poor diet, alcoholics may also short themselves on other brain-healthy essentials, like DHA.

Alcohol abuse wreaks its havoc elsewhere in the body, too, most notably in the liver, which can have a secondary effect on the brain. In long-term alcoholics, severe liver problems cause elevation of blood ammonia levels, which can lead to hepatic encephalopathy. This causes a variety of mental health issues, including shortened attention span, confusion, and tremors. Alcohol abuse is also tied to other brain-draining conditions, such as stroke and depression.

5

Eventually, alcoholics develop alcoholic dementia.

Some chronic alcoholics develop a serious disorder called Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, a disease that leads to vision problems, coordination problems, difficulty walking, disorientation, and learning and memory problems. These patients have severe brain atrophy, along with small hemorrhages in certain brain structures that are important for memory.

Your Brain on a Binge

If you think you’re off the hook because you’re not an alcoholic, but you sometimes overindulge in alcohol, you may want to reconsider. There’s evidence that even binge drinking—heavy drinking that occurs sporadically—may do damage to the brain, especially if it occurs when the brain is still developing, in young adulthood. (Keep in mind that about 46 percent of young adults now report binge drinking,

6

so the practice is strikingly common.)

In one study of 122 Spanish college students aged eighteen to twenty, for example, researchers at the Universidade de Santiago de Compostela found that binge drinkers differed from their non-bingeing peers when it came to performance on cognitive tests.

7

As compared to sixty non-binge-drinking men and women, sixty-two binge drinkers had difficulty with performance in tests of attention, fluency, and abstract design. They also showed evidence of perseveration, which reduced mental flexibility. Researchers concluded that these results may indicate frontal lobe dysfunction or developmental delay in the binge drinkers.

These findings were bolstered by an imaging study that showed actual damage on MRIs. This study, presented to the Research Society on Alcoholism in mid-2011 by University of Cincinnati researchers, looked at the brains of twenty-nine eighteen- to twenty-five-year-olds who engaged in weekend binge drinking.

8

MRIs of the binge drinkers’ brains showed a thinning of the prefrontal cortex.

Fortunately the study also offered evidence that abstaining from alcohol after binge drinking allowed the brain to recover, an outcome we can chalk up to the beauty of plasticity. But since we don’t have good studies showing the long-term effects of binge drinking—or how much the brain recovers after binge drinking—I recommend erring on the side of caution.

What does that mean, exactly? I tell all my healthy patients that one or two glasses of alcohol (one for women, two for men) per day is probably beneficial, as long as they don’t suffer from any memory or thinking problems. But anything more is risky, and regular heavy drinking is riskiest of all. For people with memory complaints, I advise avoiding alcohol altogether. Even a drop of alcohol is too much, I tell them.

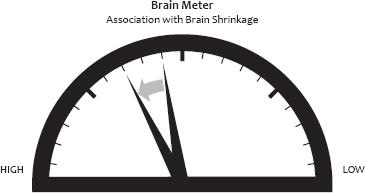

Alcohol abuse is associated with brain shrinkage. A long-term habit of consuming more than four servings a day of alcohol increases the damage; the more you consume, the worse the damage.

Have a Smoke?

You know smoking damages the brain. But we’re beginning to understand more about just where in the brain smoking hits hardest. We now know that smoking thins part of the frontal lobe called the orbitofrontal cortex, an area that’s been tied to both impulse control and rewards.

9

Heavier smokers have pronounced thinning in this area, suggesting smoking may take a cumulative toll on the brain. This might also explain, in part, why smokers find it so hard to quit: they’ve damaged the very part of the brain they need to help them control their impulse to light up.

Getting Better

When Lara left my office she was committed to ditching the alcohol, and reviving her brain. Although moderate alcohol use has benefits, I advised her (as I advise all my patients with memory problems) to gradually reduce her alcohol intake and then avoid alcohol entirely. She joined my brain fitness program and with the help of a psychologist, an exercise physiologist, and an EEG neurofeedback trainer, over the next twelve weeks she lowered her alcohol consumption, improved her fitness, stimulated her memory, and retrained her brain.

Fortunately for Lara and others like her, some of the damage done by alcohol can be rapidly undone. One study, for example, followed fifty patients admitted for an alcohol withdrawal program in Germany and found that three months of abstinence seemed to reverse some of the damage to the brain.

10

When first evaluated, study subjects’ MRIs showed brain shrinkage. Three months later (during which time patients abstained from alcohol), MRIs showed parts of the brain, especially the cingulate gyrus—important for emotion and mood—had grown in size. Patients who relapsed during the study period didn’t see such volume growth.

Another study conducted by some members of the same research team found that just two weeks of abstinence produced measurable—but not complete—reversals of volume loss in several brain areas.

11

This is yet another example of the brain’s remarkable neuroplasticity and capacity to quickly heal itself.

In fact, abstinence brings about a burst of regeneration of brain cells, as one study in animals showed.

12

In that study, animals were given ethanol to mimic four days of binge drinking, which, as expected, resulted in atrophy in the hippocampus. After abstinence, though, researchers were able to see the birth of new neurons across the hippocampus. This was a striking difference compared to the animals who continued to receive alcohol.

In my experience, alcoholic patients who stop drinking and work to improve brain health often see their walking and memory improve within six to eight months.

Fortunately for my patient, Lara, abstaining from alcohol and engaging in extensive brain training resulted in dramatic improvement. In her favor, she had the advantage of not having significant other factors—obesity, high blood pressure, or diabetes—shrinking her brain. And her years of cognitive stimulation as a professor had no doubt helped her enter her later years with a healthy brain reserve.

Got a Problem?

Evaluate your drinking habits honestly. Do you have a drinking problem? If a sincere assessment of your drinking leads you to wonder whether it falls in the unhealthy range, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism suggests asking yourself these four questions:

• Have you ever felt you should cut down on your drinking?

• Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking?

• Have you ever felt bad or guilty about your drinking?

• Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover?

If you answer yes to one or more of these questions, you may be abusing alcohol. A health care professional should be able to help you seek further assessment or help.

It’s especially important to be under the care of a doctor as you stop drinking. Stopping abruptly can trigger seizures, so it should be done only under the close supervision of a medical professional. After a gradual period of detoxification, recovering alcoholics typically need to spend time in rehabilitation and then will need support to maintain sobriety.

I

’

M RARELY ALONE

at parties. I often find myself surrounded by a circle of family or friends who pepper me with questions about memory and aging. Sometimes they’re merely curious about the latest research in the field, but often it’s more personal than that: they’re worried about what’s going on in their own brains.

Inevitably someone will launch into a discussion of his latest lapse, sheepishly describing the time he walked out of a mall, bogged down with shopping bags, and spent thirty minutes wandering the rows of sedans and SUVs in an increasingly desperate search for his car. Or the sinking feeling he had when he realized—too late—that he’d missed an important meeting. Or how he will purposefully stride into a room and then forget, the moment he passes through the doorway, what he came for. Eventually, he’ll nervously joke, “I swear, I’m getting Alzheimer’s. Right?”

It’s a common fear. In fact, in a Shriver Report poll conducted in 2010 and reported in

TIME

magazine, 84 percent of respondents said they were concerned that they or someone in their families would be affected by Alzheimer’s disease.

But is it a reasonable fear? For the vast majority of the people who ask me if they have Alzheimer’s disease, the answer is no. They don’t have the disease but instead are experiencing the normal mild memory problems and slowed mental processing that can come with age.

1

A small number of people, however, may well be at the start of cognitive decline that has at its root a mix of factors and may eventually lead to late-life dementia. And an even smaller number—a tiny fraction—of the people I meet in social situations are experiencing the start of a pure form of Alzheimer’s disease that strikes people in their fifties and sixties. How do we know who has what? And is there anything we can do to alter the course? The truth is that answering these questions is a little more complicated than you might think (but it’s fascinating!).

What Party?

Remember Sara, the baby whose brain development we followed in chapter 1? Imagine Sara as a sixty-year-old. At this stage of life it would not be unusual for her to experience age-associated memory impairment, a relatively benign condition that occurs naturally as we age and results in minor memory lapses and a slight reduction in the brain’s processing speed. That slowing would explain why Sara’s grandchildren might handily beat her at the game of Whac-a-Mole, which requires quick reaction times, but not at chess, which relies more heavily on strategy, planning, and experience. Sara might misplace her keys or experience tip-of-the-tongue syndrome, where a word she’s seeking seems maddeningly just out of reach. But with age-associated memory impairment, she wouldn’t experience a serious decline in her thinking or her daily functioning.

If Sara’s thinking or memory problems exceeded the level deemed normal for her age, she might be diagnosed with

mild cognitive impairment

(MCI), a middle ground between normal brain aging and dementia. With MCI, Sara might regularly forget conversations she had with her husband (and be met with “I told you that four times already!”) but she would still function fairly well at work and at home. Sara could still drive, dress herself, cook, clean, and pay bills. She would, however, have an increased risk of developing dementia.

Dementia

is a broad umbrella term used for people with serious brain atrophy causing profound and progressive decline in memory, along with problems in one or more other areas of cognition such as decision making, calculations, or orientation. If Sara developed dementia, she might start out with mild memory loss but quickly progress to confusion and, eventually, an inability to function. Dementia can have many causes, including stroke, life-long alcohol abuse, viral infections, severe TBI (as in boxers), HIV, or neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, or Lewy body dementia, in which different sets of brain cells die for unknown reasons. If Sara’s doctors couldn’t pinpoint a single cause but determined that more than one factor contributed to her dementia, she might be diagnosed as having “mixed dementia,” although such a diagnosis isn’t used anywhere near as much as I believe it should be (as you’ll soon read).