Boost Your Brain (34 page)

Authors: Majid Fotuhi

At the start, about one-quarter of the bariatric surgery candidates studied had below average cognitive performance—so much so that their scores placed them in the “impaired” range, chiefly due to deficits in memory and reasoning abilities.

But three months after surgery, patients who’d lost the most weight substantially improved their memory performance. (Those who didn’t lose weight, meanwhile, saw their scores decline twelve weeks later.)

Even when the weight loss itself is less dramatic, the results can be long lasting. Researchers in one diabetes prevention program found that overweight people who had modest weight loss—about fourteen pounds—were able to drastically reduce their likelihood of having diabetes. Even better, the benefits of such weight loss can persist for ten years, even if the person regained some of the weight during that time.

Randall’s many interlocking health problems—OSA, depression, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure—actually offered us many avenues for improvement. And every small step toward better physical health would be one step away from further cognitive decline.

But

really

growing Randall’s brain would require him to do something massive. Randall would have to lose a tremendous amount of weight. Now, this is no small challenge, as Randall knew. He didn’t get to 450 pounds overnight, after all. Instead, his extreme condition had developed over years, starting with some excess weight and then snowballing, with the ever-mounting toll of an interconnected set of conditions. As he piled on the pounds, for example, he developed obstructive sleep apnea, which contributed to the development of depression. The effects of OSA and depression left him fatigued and unmotivated, slowing his activity level dramatically. With less activity, Randall gained yet more weight. Soon, that extra weight triggered knee pain that kept him off his feet entirely. High cholesterol and high blood pressure, meanwhile, slowed the flow of blood to his brain, setting off silent strokes that subtly hampered his brain function.

Over time, Randall would work with my staff to improve his overall health by increasing his exercise, changing his diet, lowering his blood pressure and cholesterol, and treating his depression and sleep apnea. Exercise would help to not only grow his brain but also reduce his insulin resistance. A high-protein, low-carb, brain-healthy diet, as I described in

chapter 5

, would also help.

Changing his body would help Randall grow his brain. But he would also have to change his brain in one key way: he would have to override his brain’s faulty reward system again and again, until it reset itself and began functioning as it had before he’d become overweight. Eventually, his prefrontal cortex would be back in action—so much so that making healthy food choices would actually be easier. That, of course, would help him change his body.

All of it would rely on neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to grow and change—which, as you now know, we all possess. Even Randall, whose downward spiral was so pronounced, could change his brain and reset his course on a path that would send him instead spiraling

up

to a bigger, better brain.

Of course, it all starts with one key step: recognizing that your approach to eating and exercise needs a serious overhaul. Randall had his aha moment sitting in his wheelchair in my office, with his MRI results on the computer screen before us. Once he connected his cognitive symptoms with his health problems, he was energized like never before. Always a thinker and a planner, he quickly came up with a concrete path forward: immediate dietary changes followed by knee surgery, then exercise and enough weight loss to allow him to qualify for bariatric surgery. After surgery, he would continue to work on his diet and exercise, helping him lose weight and maintain those results.

Randall followed through on his plan and after his bariatric surgery, he continued to work on his diet and exercise, dropping down to just over 200 pounds. With the weight off and his health vastly improved, Randall reported feeling mentally stronger and clearer than ever. Best of all, his fear of Alzheimer’s had become a distant memory.

I often have my patients sit down and write up a specific action plan. In fact, it’s part of their brain fitness program passport. When they do, I always remind them to be realistic, shooting for one to two pounds of weight loss a week rather than rapidly dropping weight. And I advise them to spend time seeking out a weight-loss solution that meets their unique needs. I’ve had patients who have loved the social support they got by joining groups like Overeaters Anonymous or any one of the many group-oriented weight-loss programs. Others have found online, individualized tools work best, while still others have found certain cookbooks or diet books to guide them. As long as it promotes responsible weight loss, the method is less important than the end goal: upending that downward spiral and riding the result to a bigger brain.

Brain Attacks, Large and Small

I

F YOU’D SEEN

him rattling off figures in the boardroom or locking up his latest multimillion-dollar deal, you’d never have suspected that my patient, sixty-two-year-old Marc, was about to suffer a stroke. Vibrant and energetic, he looked anything but unhealthy. Looks can be deceiving, though.

Marc, who lived in Philadelphia and traveled frequently, had a high-stress lifestyle, plus high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and a years-long habit of getting by on three or four hours of sleep a night. Marc admitted he had a classic type A personality. In recent years, he’d been feeling increasingly tired. Then, walking out of a meeting one afternoon, he noticed that his left hand was clumsy and his walking unsteady. He chalked up the strange sensations to too many hours in the office and decided to leave early that day. Hours later, with his hand still feeling clumsy, he finally called his primary care physician, who advised him to head to the emergency room immediately. Once there, Marc got some bad news. An MRI of his brain showed an apple-size stroke in his cerebellum—the brain region important for coordination and balance.

Marc was stunned to find himself among the roughly eight hundred thousand Americans a year who suffer a stroke. Like many, he’d always viewed a stroke as a tragedy that befalls only the very ill or elderly.

As upsetting as the news was to him, it was about to get worse. When he came to see me, I discovered that Marc’s blood pressure was a shocking 170 over 110 and his pulse was 100. He also had borderline sleep apnea, borderline diabetes, and a memory performance that was below average for his age and education level. I explained to him that his stroke was just the tip of the iceberg. The conditions that had led to it, after all, were still quietly at work. Not only could they work to shrink his brain on their own, but they were also no doubt producing microscopic strokes too small to be seen on an MRI. And if his underlying health problems remained untreated, they could lead to more small strokes or even a major stroke within months.

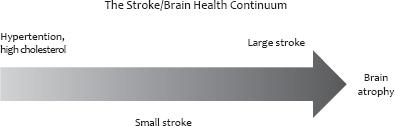

In fact, just as the brain-shrinking effects of obesity (or sleep, or stress) progress along a continuum, so too do the effects of restricted blood flow to the brain, with vascular risk factors like high cholesterol and hypertension on one end, small strokes in the middle, and a major stroke on the other end.

Marc, who’d always been “too busy” to worry about reducing his stress, lowering his blood pressure and cholesterol, exercising, and getting adequate sleep, would have to change his life to save his brain. He could do it, but first he’d have to understand why he developed a stroke and how strokes can be prevented.

Higher Pressure, Smaller Brain

Marc’s stroke happened for a reason. It occurred because blood flow in his cerebellum was blocked.

His high cholesterol played a part in creating that blockage. As you’ll probably recall from my discussion of excess weight and obesity, high cholesterol causes plaques that can build up and narrow blood vessels. Those narrowed vessels slowed the flow of blood, and thus oxygen, within Marc’s brain. But they also raised his blood pressure by forcing his heart to pump harder to push blood through. Hypertension then worsened the already bad situation in a plaque-filled blood vessel, helping to thicken and stiffen the blood vessel even more.

Like high cholesterol, hypertension is a major risk factor for stroke and brain atrophy. But even in the absence of a major stroke, the vascular damage caused by high cholesterol and hypertension result in lower blood flow to the brain, shrinking synapses, damaging brain highways, and killing cells.

The result is a smaller brain, as researchers discovered at the Institute for Ageing and Health at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne in the United Kingdom. Those researchers examined brain MRIs of 103 people with hypertension and 51 without hypertension.

1

They found that even moderate hypertension resulted in smaller overall brain volume, a smaller hippocampus, and increased white matter damage.

Hypertension Risk Factors

Hypertension affects sixty-eight million American adults, according to the Centers for Disease Control. It typically produces no obvious symptoms and thus often goes undiagnosed. Risk factors for hypertension are:

• excess weight,

• a high-sodium diet,

• diabetes,

• alcohol abuse,

• inactivity,

• smoking, and/or

• obstructive sleep apnea.

Hereditary factors can be at play too.

Hypertension in midlife has also been linked to an increased risk of cognitive decline in late life.

2

In one study, researchers first examined study subjects while they were in midlife and then checked back twenty-five years later. Those who’d had untreated hypertension in midlife were 2.6-fold more likely to have Alzheimer’s disease later in life. Researchers have also found that earlier hypertension is tied to smaller overall brain volume and evidence of numerous silent strokes later in life.

A Concern for All Ages?

There’s growing evidence that the brain-shrinking effects of hypertension aren’t just a worry for late life. In fact, researchers are beginning to uncover proof that the cognitive effects of hypertension may be felt far sooner than we once thought.

One such expert is my colleague Dr. Charles DeCarli, a stroke specialist who is a professor and director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Center at the University of California, Davis. Dr. DeCarli has long studied the effects of vascular risk factors on the aging brain. In a 2011 study published in the journal

Neurology,

Dr. DeCarli and his team reported their findings regarding 1,352 participants in the Framingham Heart Study, who were in their midfifties when first assessed for vascular risk factors and had no signs of dementia, stroke, or other neurological disorders.

3

Looking at brain scans and cognitive testing performed ten years after the subjects had first been enrolled, the research team found that people who’d had hypertension in midlife were more likely to show signs of white matter damage on their brain MRIs and worsening executive function on cognitive testing. It was new proof that the harm from midlife hypertension can be seen in subjects who were far from old.

In fact, hypertension likely starts to make its mark in the brain even before midlife, says Dr. DeCarli, who plans to do further research to find out just when that happens. It’s especially important given the growing number of obese and hypertensive children who, if allowed to remain so, may enter midlife with a considerable load of damage marring their brains.

Stroke: A Brain Killer

Chances are you hear rather regularly about strokes. We’re constantly reminded, especially as we age, that strokes kill. After all, stroke is the third leading cause of adult death in the United States (behind only heart disease and cancer) and

the

leading cause of disability in adults.

But if, like Marc, you’ve never paid attention to the details of stroke, now is a good time for a refresher course.

A stroke is the death of brain cells that occurs when blockages in the arteries in the brain or bleeding in the brain prevent blood from flowing to the area. Without the oxygen and nutrients blood brings, the affected neurons die.

A “hemorrhagic” stroke occurs when a blood vessel ruptures—as can happen with very high blood pressure or a sudden spike in hypertension—cutting off blood flow to a part of the brain. In a minority of cases, an irregular heartbeat—called atrial fibrillation—causes the formation of blood clots in the heart, which then travel to the brain, block blood vessels, and cause “embolic” strokes. But most strokes are “ischemic” strokes, which occur due to vascular disease that thickens, stiffens, narrows, and eventually clogs a person’s blood vessels.