Brain Over Binge (20 page)

Authors: Kathryn Hansen

In therapy, I indeed empowered the old pattern. Therapy made me devote more time and thought to my binge eating, when I really wanted to devote less. Therapy made me focus attention on my bulimia and its supposed causes and triggers, when I really wanted to focus attention elsewhere. In this way, I believe therapy made the faulty brain pathways that drove my habit stronger, when I really wanted to weaken them. By going to frequent therapy appointments, journaling, and analyzing my behavior, I only honed the neurological connections that supported binge eating. Therapy gave more life to my faulty neural pathways, when I really wanted to destroy them.

Therapy also taught me to connect almost everything in my life to binge eating—my past, my emotions, my daily stressors and problems, my relationships, and my personality. This only made me think about my eating disorder in many situations when it wasn't necessary. I didn't only connect my eating disorder symbolically to nearly everything in my life. Every time I decided that I binged because of a certain trigger—a social situation, a family problem, a negative feeling—I created a connection in my brain between the supposed trigger and the binge. When I again encountered the trigger, I automatically experienced an urge to binge by pattern of association (see Chapter 35). Based on what I now know about the brain, it would have been much more helpful for my therapists to advise me to separate my bulimia from all the other issues in my life, therefore allowing me to think about binge eating less and weaken the habit more.

Although my therapists and the self-help books I read were well-meaning, I don't think they led me in the right direction. It is possible that I am the one to blame for the failure of my therapy. Maybe I misinterpreted some therapy concepts so that I strengthened my habit instead of weakening it; maybe I didn't do therapy correctly; maybe I just wasn't good at uncovering and resolving issues from my past; maybe I wasn't skilled enough at deciphering and coping with a multitude of triggers; maybe I was too weak to give up all sugar; maybe I didn't devote enough time to therapy goals because I had other things I wanted to do and had to do. However, considering the rather low success rates of eating disorder patients in therapy, I was not alone. Even though therapy does help some people overcome eating disorders, it was not the right path for me.

23

: Revisiting Recovery: How Did I Do It?

S

o far, I've explained why I binged (because of my urges to binge), why I had urges to binge (survival instincts and habit), and why I followed those urges. But how was I able to recover? How was I able to terminate all my binge eating?

Since there was only one cause of each and every binge (urges to binge), all I had to do to recover was stop following my urges to binge. This was the cure for my bulimia, as I'll explain below.

Once I binged many times, I created strong, organized neural pathways that automatically generated my seemingly irresistible urges. I've termed this my "binge-created brain-wiring problem." This problem was the physical expression of my habit in my brain. The more I binged, the stronger the neural pathways that drove my habit became, which prompted me to binge eat even more. Whether it was a habit of excess, a habit of pleasure, or a habit of impulsivity—or a combination of the three—my brain was just doing its job, maintaining the habit it had learned.

When I decided to quit binge eating, I had a roadblock to face. I couldn't just say,

OK, brain, I'm done binge eating, so turn off those irresistible urges.

It didn't work that way. Once the habit was established, there was no way to turn off my urges except to retrain my brain. I had to reverse my binge-created brain-wiring problem so that it stopped producing urges to binge. Reversing my brain-wiring problem was quite simple:

How did I create my brain-wiring problem in the first place?

By acting on my urges to binge many times.

How did I reverse my brain-wiring problem?

By

not

acting on my urges to binge many times.

It was straightforward: to reverse my brain-wiring problem, to undo my habit, I had to stop following my urges to binge. That was the simple truth that often eluded me in therapy as I was focusing on the deeper emotional meaning of my binge eating. While I was in therapy, I held out hope that my urges to binge would just go away. Since I couldn't seem to fight them using willpower, I hoped that if I kept working in therapy—exploring the underlying issues and learning to cope with triggers—the urges would disappear on their own. They did not.

No matter how much progress I was making dealing with emotional issues in therapy, my urges would never go away as long as I kept acting on them. As long as I continued following my urges, my brain kept strengthening the neural connections and pathways that produced them and strengthened the habit.

The good news for me was, when it comes to the brain, what you no longer use, you lose

155

—not in a metaphorical sense, but in a real, physical way. The brain is an extremely efficient organ. It builds and fuels the neural connections and pathways that are frequently used, and it weakens and prunes the ones that aren't. When a person stops performing a behavior, the neural connections that supported that behavior simply fade. In other words, "if you don't exercise brain circuits, the connections will not be adaptive and will slowly weaken and could be lost."

156

This was the case with my habit of binge eating.

From the first time I had an urge to binge and didn't act on it, I began teaching my brain that my habit was no longer necessary. In turn, my brain began to correct my binge-created brain-wiring problem by weakening the neural connections and pathways that supported it, wherever the exact location of those pathways may have been. As I experienced more and more urges that did not lead to binge eating, my brain learned that I no longer needed the habit. The faulty neural pathways that once led me to the refrigerator weakened with lack of use "until they [were] able to carry signals no better than a frayed string between two tin cans in the old game of telephone."

157

I couldn't teach my brain this lesson by arguing or trying to rationalize with it. I could teach my brain this only through my own repeated actions. In other words, I couldn't talk my brain out of my habit, I had to act it out. By not acting on my urges, I physically corrected my brain-wiring problem. I had to make those willful behavioral changes; then my brain fell in line and turned off my urges to binge. Once I decided I wanted to take a different path than the one my brain had carved out for me, I, my true self, had to go down that different behavioral path

before

my brain. Then my brain followed, not the other way around.

Rational Recovery

gave me a simple thinking skill that turned out to have incredible power—the power to rewire my brain, completely erasing my bulimia. I didn't realize it at the time, but I was actually utilizing the plasticity of my brain to end my habit. The same property of the brain—neuroplasticity—that created my habit completely erased it. This was possible only because of the capabilities of a specific region of my brain, the prefrontal cortex.

THE KEY TO RECOVERY: MY PREFRONTAL CORTEX

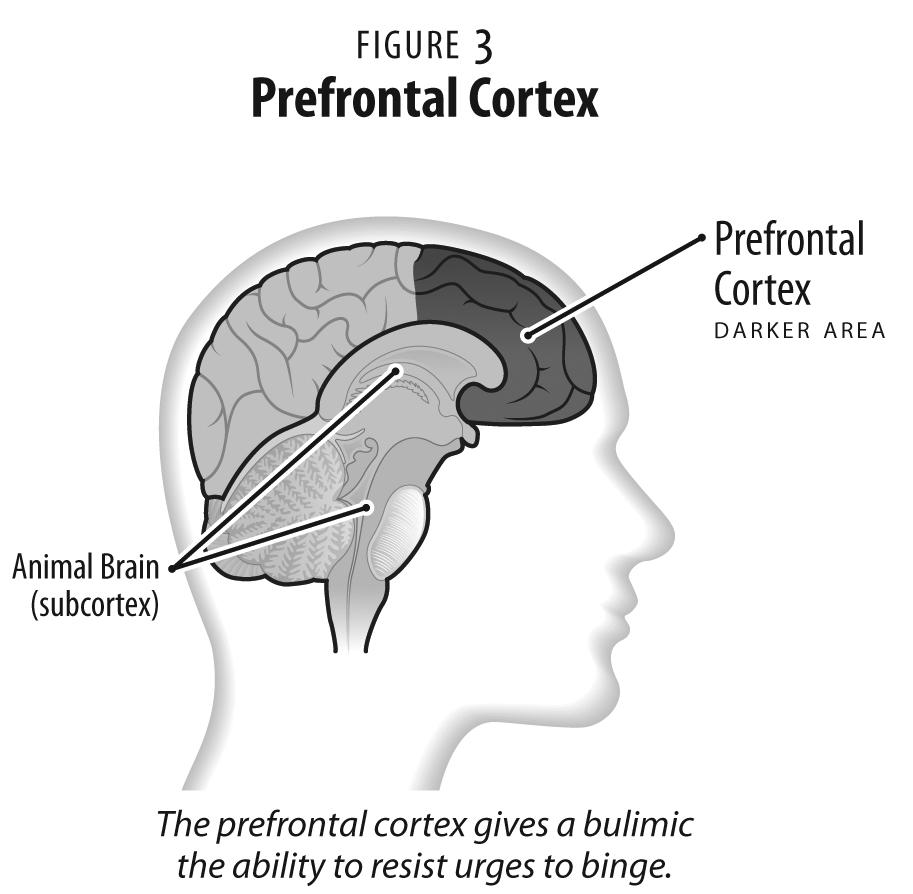

Whether my binge eating habit was a habit of excess, a habit of pleasure, or a habit of impulsivity—or, as I believe, probably a combination of the three—part of me still remained apart from it at some level; otherwise, I would not have been able to put an end to the habit. The part of me that remained unaffected and directed my recovery was my prefrontal cortex—a brain region I talked about briefly when discussing the teen brain in Chapter 17.

The prefrontal cortex—the most evolutionary-advanced part of the brain that gives us our sense of identity and capacity for voluntary action—makes up the largest part of the frontal lobe (see

Figure 3

).

158

Compared to our animal ancestors, we have a very large frontal lobe, which occupies much more of our total brain than for any other creature.

159

The frontal lobe has connections to other parts of the brain and can inhibit those parts, giving humans the ability to stop and think and divert primitive responses.

160

Humans don't have to follow every impulse from their brains, and the prefrontal cortex is vitally important in this ability. The prefrontal cortex has the greatest role in inhibiting behavior and withholding automatic responses.

161

The prefrontal cortex is the seat of the will—of freely preformed volitional activities.

162

In order to binge, I had to use willful voluntary muscle movements (acquiring food, putting it in my mouth, chewing and swallowing it), all of which my prefrontal cortex had complete power to stop me from doing. No matter what thoughts, feelings, or cravings my animal brain generated automatically, I could choose my actions because of my prefrontal cortex. I could stop myself from performing "inappropriate motor actions."

163

My prefrontal cortex had this power because of its role as the brain's command post, chief executive, or "conductor of the orchestra."

164

The prefrontal cortex is the best-connected part of the brain, meaning that it communicates directly with all functioning parts of the brain, including the animal brain.

165

Since it is the agent of control within the brain and central nervous system,

166

its job is "coordinating and constraining" those neural structures.

167

It was the prefrontal cortex that gave me the ability to say no to—or use veto power over—my urges to binge. Veto power is a type of willpower that psychologist Richard Gregory first called "free won't."

168

Without getting into a philosophical discussion of free will that is beyond the scope of this book, I'll say that free will does not necessarily work by initiating voluntary actions, but instead, it works by allowing or suppressing those voluntary actions.

169

In other words, we may not have the capacity to choose what actions the brain automatically prompts us to perform; but because of our prefrontal cortex, we can choose which of those automatic promptings to follow and which ones to disregard.

When I stopped acting on my urges, I was using veto power. Without being able to describe the process at the time, I had in fact discovered the ability of my own prefrontal cortex to disregard my lower brain's automatic signals. I realized that, despite my intrusive thoughts, powerful feelings, and strong urges, my prefrontal cortex could indeed suppress inappropriate actions. I discovered "free won't"—the ability not to act—and by not acting over and over, I corrected my binge-created brain-wiring problem.

I believe the prefrontal cortex is the specific region of what

Rational Recovery

calls the "human brain" or the "I" that gave me the ability to recover. It certainly wasn't necessary for me to know the technical details of my brain anatomy to recover; but now that I do know more, I can better explain how I was able to say no to each and every urge to binge. As I do so, I hope it will help others discover the power of the prefrontal cortex as well.

FIVE STEPS I USED TO STOP BINGE EATING

The next five chapters describe my recovery, step by step. When I stopped binge eating, I was not consciously thinking that I was following a set of steps, but shortly afterward, I could look back and see exactly what I did that enabled me to use my prefrontal cortex to quit—some of it derived from the advice I read in

RR

and some from my own insights.

Here are the steps that corrected my binge-created brain-wiring problem and brought my bulimia to an abrupt end:

Step 1:

I viewed my urges to binge as neurological junk from my lower brain.

Step 2:

I separated my highest human brain from my urges.

Step 3:

I stopped reacting to my urges.

Step 4:

I stopped acting on my urges.

Step 5:

I got excited.

The first three steps made the fourth step possible; and once I practiced the fourth step for long enough, my urges to binge disappeared. The fifth step was a natural result of my success in resisting urges, but I believe it turned out to be very important to speed up and cement the brain changes that erased my habit.

BRAIN OVER BINGE

Together, the five steps I used comprise what I mean by "brain over binge"—thus the title of this book. This concept is definitely an offshoot of "mind over matter" because it was my mind—my true self, my prefrontal cortex, my highest human brain—that had the capacity to override the harmful matter, my urges to binge, coming from my animal brain. The prefrontal cortex lies structurally above and forward of (over) the animal brain; therefore, my recovery was not only mind over matter, it was—quite literally—brain over binge.

In the chapters that follow, I'll often refer to the five steps of my recovery as simply "brain over binge." To illustrate this and draw the distinction between lower and higher brain functions, I will also begin referring to the animal brain as simply the "lower brain" and the prefrontal cortex or the true self as the "highest human brain." This takes the two brain functions at work in bulimia down to their most basic forms. When I use the term

lower brain

throughout the remainder of this book, I am referring to the parts of the brain and nervous system that automatically produce urges to binge, regardless of specific location.

Like I have previously said, the brain and nervous system are not understood well enough yet to be able to pinpoint the specific regions and peripheral functions that create the urges, so even saying "animal brain" has been somewhat of a stretch. However, I can say with confidence that the urges arise automatically in regions of the brain and nervous system inferior to the prefrontal cortex—that is, in lower brain centers. I can also say with confidence that the prefrontal cortex—the most sophisticated and highest (in ability and mostly in anatomy) part of the human brain—gives us the capacity to override the automatic impulses from the lower brain. This is why I will keep things simple, talking about just the lower brain versus the highest human brain.