Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (25 page)

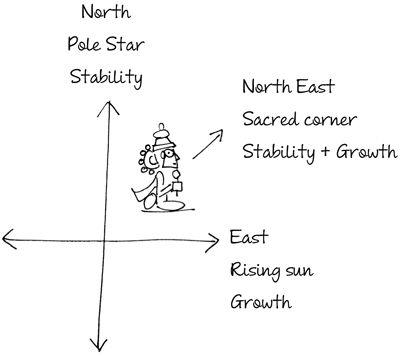

Each deity is kept facing the east, or the direction of the rising sun, a symbol of growth. The yajaman stands where the sun is supposed to be, suggesting that the yajaman hopes to bring in the same value as the sun, contribute to the growth of every devata he invokes. Also implicit in this arrangement is that the yajaman favours his devatas more than the rising sun. He chooses to face the devatas rather than the sun, acknowledging that without them he cannot grow.

Each deity is given his/her favourite food, flower and leaf. Shiva is given raw milk and bilva leaf while Krishna is given butter and tulsi leaf— recognition of the fact that while some needs like growth and stability may be common, every devata's tastes are unique. The more we customize the svaha, the more likely we are to delight the gods.

The puja room forces the yajaman to look at each devata as an individual, not as part of a collective. Often people look at organizations and forget they are sets of people. And we have to deal with people, not sets. Each person has his own strength and weakness, and he would like them to be at the very least acknowledged. A company with five thousand employees actually has five thousand individual vision statements. But typically, we focus only on one, that of the impersonal institution. This may be efficient, but it does dehumanize the organization.

At the annual internal conference, Inderjit is busy networking with the many partners of the consulting firm. When he meets Sorabh, he talks about the latest gadgets. When he meets Rathor, he talks about cricket. When he meets Satyendra, he talks about philosophy. When he meets Yamini, he talks about films. He never talks business with any of them. He knows that they are all tired of work and want to relax at parties. He also knows that they are bored and need entertainment. What better way to get entertained than talk on their favourite subject. Inderjit thus ensures every devata gets his favourite bhog. His performance is above average but not great. But his ability to make every partner smile has contributed to his being on the fast career track in the firm. The senior partner, Jagdish, who observes Inderjit make his moves, comments to Yamini, "If he can do the same with clients, we can be sure business will flow."

Every devata matters depending on the context

In the nineteenth century, when European orientalists first translated Vedic hymns, they noticed that each hymn evoked different gods. Naturally, they assumed Hindus were polytheists like the Greeks. Then they noticed that each time a deity was being invoked he was treated as the supreme god, suggesting Hindus were monotheists like the Christians. This confused them. Were Hindus polytheistic or monotheistic? Monotheism was seen as superior back then and the British did not lose a single opportunity to embarrass Indians about their many gods.

Some suggested Hindus were henotheistic; they worshipped only one god but acknowledged the existence of others. Max Mueller came up with the term kathenotheistic, which means every god is treated as the supreme god turn-by-turn at the time of invocation. In other words, context determined the status of the god. In drought, Indra who brought rains was valued. In winter, Surya, the sun god was admired. In summer, Vayu, god of the winds was worshipped. And so it is in business. Everybody we deal with in business is important. But their importance soars as our dependence on them increases. Importance is a function of context, which makes all businessmen followers of kathenotheism.

In the puja ghar, the gods are classified under various categories; personal gods are called ishta-devata; household gods are griha-devata; family gods are kula-devata; village gods are grama-devata, and forest gods are known as vana-devata. Thus, there are different gods for different contexts: the personal, departmental, regional and the market. Each deity is of value only in a particular season or at a particular place. No one is of value everywhere and at all times. Each one plays a role in our life. Individually or collectively, they bring fulfilment to our existence.

Everybody in the Delhi office resents John. He has been hired by Sethji for a very good salary but does hardly any work. He spends all day surfing the net, leaves office early and spends his evenings out in clubs, partying with the rich and famous. When questioned by his rather conservative head of accounts, Sethji says, "When I have work with government agencies, I ask John to make the calls. Because he is a foreigner, doors open for him. I get appointments. He starts the meeting and I finish it. And because of his clubbing, he invariably knows the sons and daughters of ministers and other influential people. The officers try to impress him by ensuring the work gets done without too much hassle. So you see, John is like my umbrella. Not useful everyday but certainly of great value on a rainy day. He is worth every penny I pay him."

Not all devatas are equal

Once, a child defeated Taraka, a great asura. The child had six heads, rode a peacock, had the symbol of a rooster on his banner and a lance in his hand. As the bearer of such potent symbols of virility, he was clearly no ordinary child. Who was he?

"He is my son," said Gauri, "I merged six babies into one to create this divine warlord." "He is our son," said the six Krittika stars, "Each one of us nursed those six babies since their birth." "He is my son," said the Saravana, the marsh of reeds, "I provided the fuel for the fire that transformed six seeds in a river into six babies on a lotus." "He is my son," said the river-goddess, Ganga, "My flow turned a single seed into six." "He is my son," said Vayu, the wind god, "I reduced the heat of the single seed otherwise it would have scorched dry the rivers of earth." "He is my son," said Agni, the fire god, "Only I had the power to catch that fiery seed that Vayu cooled and Ganga turned to six." "And who caused the seed to be released from the body of Shiva? It was me! I am the mother of this warrior," said Gauri again.

Gauri, Krittika, Saravana, Ganga, Vayu and Agni, six deities claimed to be the mother of the child-warlord, and each was right from their own point of view. To stop the bickering, the contribution of each of these 'mothers' was acknowledged by giving the child many names: Kumara for Gauri, Kartikeya for the star-goddesses, Saravan for the reed marsh, Gangeya for the river-goddess, Guha for the wind-god and Agneya for the fire-god. This made everyone happy. A special prayer was reserved for the father, Shiva, from whose body came the seed of which the child was a fruit.

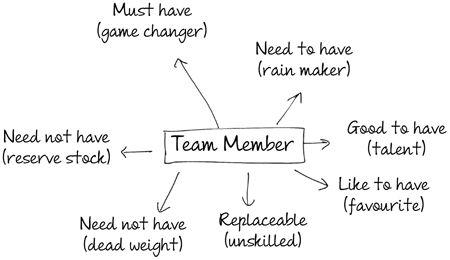

We depend on the entire team for its outputs. Every member of the team is a devata. But in teams there are always idea generators and idea implementers. It makes good sense for the yajaman to distinguish between the two. While idea implementers are essential, the idea-generator is critical.

When their advertising campaign won a prestigious global award, Rima threw a huge party where she personally thanked everyone from the planning team to the creative team and media team. Without their contribution, this would never have happened. When the crowds were gone, Rima walked up to Milind, the quiet creative head. She knew it was he who had sold the bold concept to the client. He was the cornerstone of the project. Everyone was essential; but Milind was critical, the idea-generator, the Shiva whose seed was incubated in many wombs to create Kartikeya.

Seducing multiple devatas is very demanding

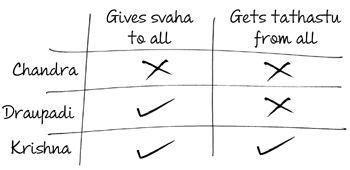

Dealing with many devatas is not easy. Chandra, the moon god, was a failure. Draupadi, the heroine of the epic Mahabharat, was a partial success, but Krishna was the most successful of all.

Though Chandra marries the twenty-seven daughters of Daksha, he prefers only one—Rohini. Only a threat from Daksha makes Chandra pay attention to his other wives. But he gives his svaha reluctantly, waning as he moves away from Rohini and waxing when he comes close to her.

By contrast, Draupadi treats all her five husbands equally and constantly tries to satisfy each of them. Even though she yearns for Arjun, her favourite, and finds Bhim most useful, she never forgets that as the shared wife of the five Pandavs she has to treat all husbands equally. To ensure there is no jealousy, she is faithful to each husband for a full year and then passes through fire, regenerating her body, before moving on to the next. She pays careful attention to everyone's hunger, making herself so dependable that none of them can bear the thought of losing her. This is not easy as every husband's hunger is different: Yudhishtir, the eldest, loves conversations on matters of state; Arjun enjoys being praised for his archery skills; Bhim loves food; Nakul loves being admired for his beauty; and Sahadev enjoys being silent. And yet, despite all her efforts, when it comes to protecting her, all the brothers fail—both individually and collectively—when they do nothing as she is being publicly abused by the Kauravs.

In the Bhagavata, Krishna dances with many milkmaids or gopikas in the forest of Madhuvan. Every gopika thinks he dances exclusively for her, so well does he meet all their demands. For that reason, the dance of Krishna and the gopikas forms a perfect circle, with each one equidistant from him despite their varied personalities. This circle is called the rasa-mandala. Here, no gopika resents the other. Just as Krishna treats them as devatas, they give due respect to him, their yajaman and strive to make him happy by being ensuring the rasa-mandala includes everyone. Krishna focuses on the personal goals of the gopikas, and the gopikas—by focusing on the personal goal of Krishna— end up meeting the organizational goal.

Seduction is truly successful only when the devatas strive to satisfy the hunger of the yajaman. The point is for the employer to get the employee to give his best voluntarily, and vice versa. When we rely on rules, regulations, reward and reprimand to get our work done, it means we want to domesticate our devatas, rather than seduce them. It means they are doing work reluctantly not joyfully.

Ever since Rehman took over as the manager of the restaurant, there has been a marked change in the energy of the place. The sweeper does not need to be supervised, the waiters do not need to be ordered around, and the cook does not need to be instructed. Everyone is taking ownership of their duties and giving their best. This is because Rehman never talks about tasks and targets, except on Saturdays. The rest of the week, he checks if everyone is happy doing their job, satisfied with what they have achieved. He nudges them gently when they slack, never admonishing or shaming them. With Rehman around, they feel less like servants and more like owners. Rehman does not see work as a fulfilment of contract; he has linked their work with their self-esteem and their self-worth. The workplace energizes everyone and so they contribute beyond the call of duty.