Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (28 page)

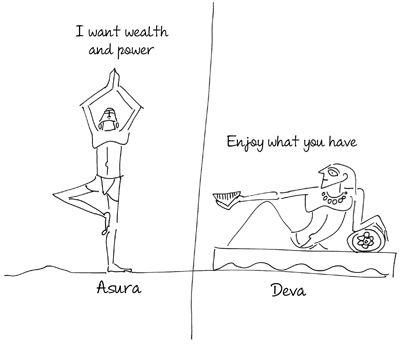

If ambition is the force, then contentment is the counterforce

Growth drives most organizations. Along with growth comes change, and change is frightening. In the pursuit of growth, one must not lose sight of the stability of things already achieved.

The most common example of force and counterforce in mythology are the devas and asuras. The devas are not afraid of death but they are afraid of losing everything they possess. On the other hand, the asuras are afraid of death but have nothing to lose, as they possess nothing. This makes devas insecure and the asuras ambitious.

The devas want to maintain the status quo whereas the asuras are unhappy with the way things are. The devas want stability, the asuras want growth. The devas fear change and do not have an appetite for risk while the asuras crave change and have a great appetite for risk. The devas enjoy yagna, where agni transforms the world around them; the asuras practice tapasya where tapa transforms them, making them more skilled, more powerful, more capable. The devas enjoy Lakshmi, spend Lakshmi, which means they are wealth-distributors, but they cannot create her; the asuras are wealth-generators hence her 'fathers'. An organization needs both devas and asuras.

They need to form a churn, not play tug of war. In a churn, one party knows when to pull and when to let go. Each one dominates alternately. In a tug of war, both pull simultaneously until one dominates or until the organization breaks.

When Sandeep's factory was facing high attrition and severe market pressures, he ensured that old loyalists were put in senior positions. They were not particularly skilled at work. They were, in fact, yes-men and not go-getters, who yearned for stability. By placing them in senior positions, Sandeep made sure a sense of stability spread across the organization in volatile times. They were his devas who anchored the ship in rough seas. When things stabilized and the market started looking up, Sandeep hired ambitious and hungry people. These were asuras, wanting more and more. They were transactional and ambitious and full of drive and energy. Now the old managers hate the new managers and block them at every turn. Sandeep is upset. He wants the old guard to change, or get out of the way, but they will not change and refuse to budge. Sandeep is feeling exasperated and frustrated. He needs to appreciate the difference between devas and asuras. Each one has a value at different times. They cannot combine well on the same team but are very good as force and counterforce during different phases of the organization. Sandeep must not expect either to change. All he needs to do is place them in positions where they can deliver their best.

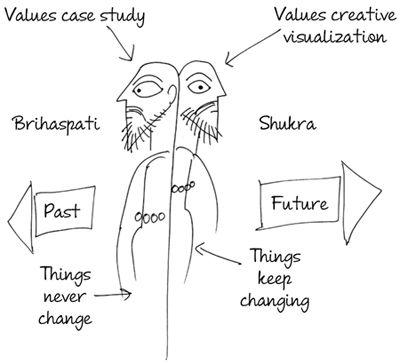

If hindsight is the force, then foresight is the counterforce

Brihaspati is the guru of the cautious and insecure stability-seeking devas. Bhrigu-Shukra is the guru of the ambitious and focused, growth-seeking asuras. Sadly, neither do the devas listen to Brishaspti nor do the asuras listen to Shukra.

Watching Indra immersed in the pleasures of Swarga, Brishaspati cautioned him about an imminent attack by the asuras. "They always regroup and attack with renewed vigour. This has happened before, it will happen again. You must be ready," said Brishaspati. Indra only chuckled, ignored his guru and continued to enjoy himself, drinking sura, watching the apsaras dance and listening to the gandharvas' music. This angered Brihaspati, who walked away in disgust. Shortly thereafter, Indra learned that the asuras had attacked Amravati, but he was too drunk to push them away.

After Bali, the asura-king, had driven Indra out of Swarga, and declared himself master of sky, the earth and the nether regions, he distributed gifts freely, offering those who visited him anything they desired. Vaman, a young boy of short stature, asked for three paces of land. Shukra foresaw that Vaman was no ordinary boy, but Vishnu incarnate and this simple request for three paces of land was a trick. He begged Bali not to give the land to the boy, but Bali sneered; he felt his guru was being paranoid. As part of the ritual to grant the land, Bali had to pour water through the spout of a pot. Shukra reduced himself in size, entered the pot and blocked the spout, determined to save his king. When the water did not pour out, Vaman offered to dislodge the blockage in the spout with a blade of grass. This blade of grass transformed into a spear and pierced Shukra's eyes. He jumped out of the pot yelling in agony. The spout was cleared for the water to pour out and Vaman got his three paces of land. As soon as he was granted his request, Vaman turned into a giant: with two steps, he claimed Bali's entire kingdom. With the third step, he shoved Bali to the subterranean regions, where the asura belonged.

Brihaspati stands for hindsight and Shukra stands for foresight. Brihaspati is associated with the planet Jupiter, known in astrology for enhancing rationality, while Shukra is associated with the planet Venus, known for enhancing intuition. Brihaspati has two eyes and so, is very balanced. Shukra is one-eyed and so, rather imbalanced. Brihaspati is logical, cautious and backward looking while Shukra is spontaneous, bold and forward-thinking. Brihaspati relies on tradition and past history, or case studies. Shukra believes in futuristic, creative visualization and scenario planning; his father Bhrigu is associated with the science of forecasting. Brihaspati relies on memory while Shukra prefers imagination. Both are needed for an organization to run smoothly.

When Rajiv was presenting his vision and business plan to his investors, he realized they were making fun of him. His ideas seemed too strange and bizarre. They said, "Give us proof of your concept." And, "Tell us exactly how much the return on investment will be." Rajiv tried his best to answer these questions, but his idea was radical and had never been attempted before. It was a new product, like the iPad had been at its inception. He would have to create a market for it. He had sensed people's need for it though this need was not explicit. It was a hidden need, waiting to be tapped. Rajiv is a Shukra—he can see what no one else has yet seen. The investors before him are Brihaspati—they trust only what has already been seen.

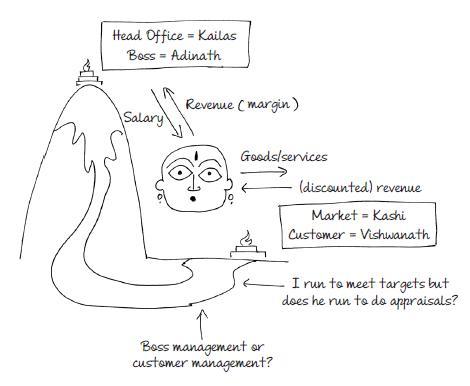

Upstream forces need to be balanced by downstream forces

The Purans state that Shiva resides in two places in two forms: he resides on the mountain in Kailas, and down by the riverbank in Kashi. In Kailas he is Adinath, the primal teacher, who offers cosmic wisdom. In Kashi, he is Vishwanath, the worldly god, who offers solutions to daily problems.

Every person is trapped between the god at Kailas who sits upstream and the god at Kashi, who sits downstream. Upstream are the bosses who sit in the central office. Downstream are the employees who face the client. Those upstream are concerned with revenue and profit, while those downstream are concerned with concessions, discounts and holidays. The yajaman needs to balance upstream hunger as well as downstream hunger.

We hope that just as we see the devatas upstream and downstream, those around us do the same. When we are not treated as devatas by other yajamans, we too refuse to treat our devatas with affection. Only when we see each other as the source of our tathastu will we genuinely collaborate and connect with each other.

At the annual meeting of branch managers, there was much heated discussion. The shareholders were clear that they wanted an improved bottom line. The bank had grown very well in the last three years in terms of revenue, but it was time to ensure profitability as well. However, the customers had gotten used to discounts and were unwilling to go along with the new strict policies that were being rolled out. General Manager Waghmare is in a fix. Kashi wants discounts while Kailas wants profit. Kashi is willing to push the top line but Kailas wants a better bottom line. He is not sure he can make both shareholder and customer happy.

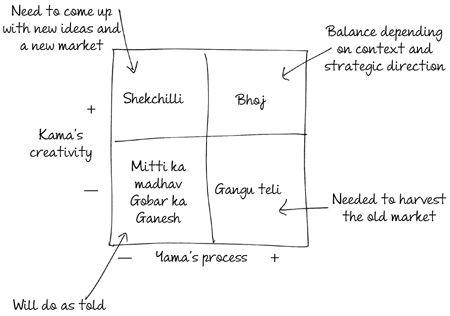

Balance is the key to avoid tug of war

Vishnu has two wives, Shridevi and Bhudevi. Shridevi is the goddess of intangible wealth and Bhudevi, the earth-goddess, is goddess of tangible wealth. In some temples, they are represented as Saraswati and Lakshmi, the former being moksha-patni, offering intellectual pleasures, and the latter being bhoga-patni, offering material pleasures. Shiva also has two wives— Gauri and Ganga—one who sits on his lap and the other who sits on his head; one who is patient as the mountains and the other who is restless as a river. Krishna has two wives, Rukmini and Satyabhama, one who is poor (having eloped from her father's house) and demure, and the other who is rich (having come with her father's blessing and dowry) and demanding. Kartikeya, known as Murugan in South India, has two wives—the celestial Devasena, daughter of the gods, and Valli, the daughter of forest tribals. Ganesha has two wives, Riddhi and Siddhi, one representing wealth and the other representing wisdom. The pattern that emerges is that the two wives represent two opposing ideas balanced by the 'husband'. Amusing stories describe how the husbands struggle to make both parties happy.

The Goddess has never been shown with two husbands (patriarchy, perhaps?). However, as Subhadra in Puri, Orissa, she is shown flanked by her two brothers—Krishna, the wily cowherd and Balabhadra, the simple farmer. In Uttaranchal and Himachal, Sheravali, or the tiger-riding goddess, is flanked on one side by Bir Hanuman, who is wise and obedient, and on the other by Batuk Bhairava, who is volatile and ferocious. In Gujarat, the Goddess is flanked by Kala-Bhairo and Gora-Bhairo, the former who is ferocious and smokes narcotic hemp and the latter who is gullible and drinks only milk. In South India, Draupadi Amman, the mother goddess, has two guards, one Hindu foot soldier and the other a Muslim cavalryman; not surprising for a land that expresses tolerance and inclusion in the most unusual ways. Once again, the pattern is one of opposite forces balanced by the sister or mother.

Balance is also crucial to business. The marketing team needs to balance the sales team. The finance team needs to balance the human resources team. The back-ends need to balance front-ends. Marketing ensures demand generation but its success cannot be quantified as its thinking is more abstract and long-term. Sales gives immediate results and is tangible, but cannot guarantee or generate future demand. The finance team focuses on processes, returns on investment and audit trails, or the impersonal facets of the company. The human resource team has to compensate this by bringing back the human touch. Back-end systems can ensure inventory and supply, but it is the front-end that has to ensure sales and service with a smile. A leader has to be the husband, sister and mother who balances the opposing wife, brother and son.