Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (27 page)

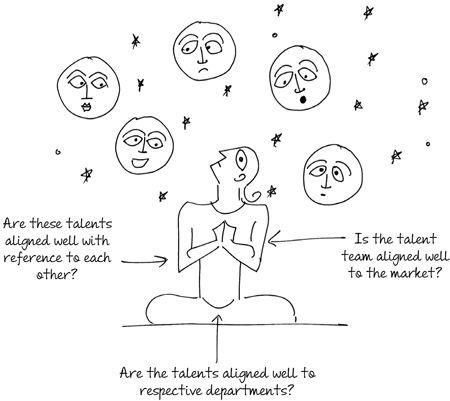

A graha is a talented devata demanding his place in the grand pantheon of the organization. In conjunction with some groups, a celestial body has a favourable impact; in others, the relationship can be disastrous. Likewise, some talents do well in a particular group and not so well in another. A manager may do well in the audit team but not in the business development team. A manager may do well as long as he is dealing with marketing matters but he may fail in matters related to logistics.

What matters most is the relationship of all the grahas with each other. If individual talents do not get along with each other, if business unit heads do not collaborate with each other, it could lead to a leadership crisis, which does not bode well for the organization.

Everybody yearns for an optimal alignment of grahas, rashis and nakshatras. This is colloquially called jog, derived from the word yoga. A yajaman who is able to design such optimal alignments on his own, or makes the best of whatever alignment he inherits, is considered a magician, a jogi. Sometimes he is also called a 'jogadu', the resourceful one, admired for his ability to improvise or do 'jugaad' with the resources at hand.

Prithviraj is the head of a telecom company with forty thousand employees. He feels like Surya, the sun, with the whole world revolving around him. Each client-facing executive is like a star that is part of a constellation which, in turn, is part of a larger constellation. He can see them but he rarely engages with them. His daily interaction is with about fifteen people who make up his core team. They are his grahas. Through them, he exerts influence over all stars, across the sky, which is his marketplace. He is aware of each graha's personality; who is restless, who is aggressive, who is moody and who gets along with whom. He works with them, helping them enhance their positives and work on their negatives, to get the fine balance that will give him the success he so desperately wants. He wants a finance head who is firm yet gentle, a marketing head who is flamboyant yet level-headed, and an operations head who is both people and numbers driven. He is getting there.

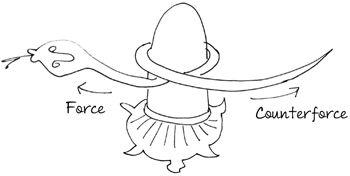

Every organization is a churn

When the devas wish to churn the ocean of milk, Vishnu suggests they take the help of the asuras, for a churn cannot work without an equal and opposite counterforce. In business, the organization is the churn while the market is the ocean of milk in which Lakshmi is dissolved. The various departments of the organization and members of the leadership team serve as force and counterforce, respectively.

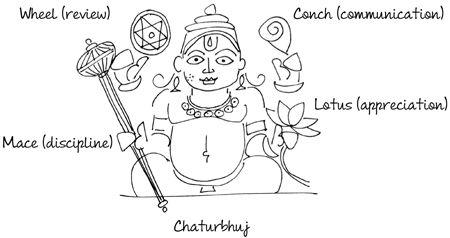

Vishnu alone knows when to pull and when to let go, how much to pull and how much to let go, who should pull and who should let go. To ensure that the churning is happening correctly, he holds four tools in his four arms. This is why he is also called Chaturbhuj, the one with four arms. Each tool symbolizes one of the four things to keep in mind when supervising any project.

- The conch-shell trumpet stands for clear communication. The yajaman needs to clearly communicate his expectations to his team.

- The wheel stands for repetition and review. The yajaman needs to appreciate that all tasks are repetitive and need to be reviewed periodically.

- The lotus is about appreciation and praise. It complements the club.

- The club stands for reprimand and disciplinary actions. It complements the lotus.

The conch-shell and lotus are instruments of seduction. The wheel and the club are instruments of violence. The yajaman needs to know when to be nice and when to be nasty, depending on the context, so that ultimately, work gets done.

When Lakshmi is not forthcoming, Vishnu knows that the churn has been damaged: either someone is pulling when they are not supposed to or someone is refusing to let go. It is then that he uses the four tools in the right proportion, as the situation demands.

Arvind has a peculiar style of management that few in his team have deciphered. When everyone is together, he enjoys visioning and planning and ideating. He publicly announces individual and team successes and takes people on celebratory lunches. When he is reviewing his team members, or pulling them up for indiscipline or lack of integrity, he only does it in private. By doing the positive things in public, he amplifies the positivity in the team. By doing the negative but necessary things in private, he avoids spreading negativity.

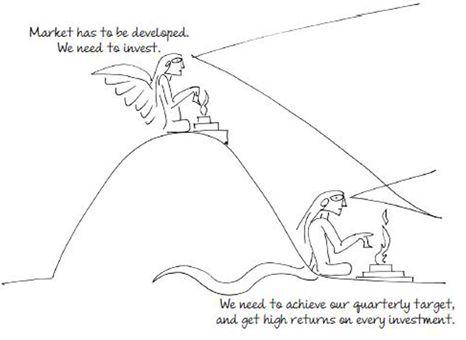

If strategy is the force, then tactic is the counterforce

Vishnu rides an eagle or garud, and rests on the coils of a serpent or sarpa, which is to say he has both a wide view, as well as a narrow view. His vision is both long-term and short-term. The big picture is garud-drishti, or the bird's-eye view or strategy. The more detailed, context-specific picture is sarpadrishti, or the serpent's eye-view or tactic.

Both these views are demonstrated in the Ramayan. Dashrath's second queen, Kaikeyi, asks him for the two boons he promised her long ago: that Ram, the eldest son and heir, be sent into forest exile for fourteen years, and that her son, Bharat, be made king instead. When Dashrath informs his sons about this, Ram immediately agrees to go into exile but Bharat does not agree to be king.

Ram agrees because he knows the immediate impact of his decision: the people of Ayodhya will be reassured that the royal family always keeps its promises, however unpleasant. Bharat disagrees because he knows the long-term impact of his decision: no one will be able to point to the royal family as being opportunists and thereby justify future wrongdoing. By demonstrating sarpa-drishti and garud-drishti, Ram and Bharat ensure the glory of the Raghu clan.

In contrast, neither view is demonstrated in the Mahabharat. Satyavati refuses to marry the old king Shantanu of the Kuru clan unless she is assured that only her children become kings of Hastinapur. Shantanu hesitates, but his son, the crown prince, Devavrata, takes a vow of celibacy, demonstrating neither sarpa-drishti nor garud-drishti.

In the immediate-term, both Shantanu and Satyavati are happy. But in the short-term, the kingdom is deprived of a young, powerful king. The old king dies and for a long time the throne lies vacant, waiting for Satyavati's children to come of age. In the long-term, this decision impacts succession planning. The Kuru clan gets divided into the Kauravs and the Pandavs, which culminates in a terrible fratricidal war.

When asked why he needed a chief operating officer, Aniruddh told the chief executive officer that he needed someone downstairs to pay attention to quarterly targets and someone upstairs to pay attention to the long-term prospects of the company. "I want the CEO to think of the five-year plans, product development and talent management, not waste his time thinking of how to achieve today's sales." Aniruddh knows that there will be tension between the CEO and COO, as the COO will have more control over the present yet will have to report to someone whose gaze is on the future. This tension between the sarpa and the garud was necessary if Lakshmi had to keep walking into the company for a sustained time.

If creativity is the force, then process is the counterforce

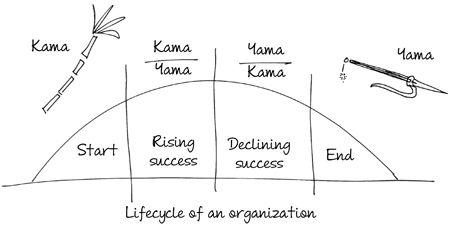

Kama is the charming god of desire and creativity. He rides a parrot and shoots arrows of flowers rather indiscriminately, not bothering where they strike. Yama is the serious god of death and destiny, associated with the left-brain. He keeps a record of everything and ensures all actions are accounted for.

If Kama is about innovation and ideas, Yama is about implementation and documentation. Kama hates structure. Yama insists on structure. Kama is about play. Yama is about work. Human beings are a combination of the two.

Vishnu is a combination of both Kama and Yama. His conch-shell and lotus represent his Kama side, as everyone loves communication and appreciation, while his wheel and mace represent his Yama side, as everyone avoids reviews and discipline.

In folklore, there is reference to one Shekchilli who dreams all the time and never does anything. He is only Kama with not a trace of Yama. Then there is one Gangu Teli, who spends all day doing nothing but going around the oil press, crushing oilseeds. He is only Yama with not a trace of Kama. Then there are Mitti ka Madhav and Gobar ka Ganesh, characters who neither dream nor work, and are neither Kama or Yama. They do what they are told and have neither desire nor motivation. Finally, there is Bhoj, the balanced one, who knows the value of both Kama and Yama, and depending on the context, leans one way or the other. Bhoj is Vishnu.

In the early phases of an organization, when ideas matter, Kama plays a key role as the vision of the yajaman excites and attracts investors and talent to join the team. In the latter stages of an organization, when implementation is the key to maximize output, Yama starts playing an important role; more than dreams, tasks and targets come to the fore. When creativity and ideas cease to matter, and only Gangu Teli is in control, the organization lacks inspiration and is on its path to ruin. Thus, the proportion of Kama and Yama plays a key role in the different phases of a company.

When the team met to brainstorm, Partho always came across as a wet blanket. As soon as an idea was presented, he would shoot it down by citing very clear financial or operational reasons. His boss, Wilfred, would tell him to keep implementation thoughts for later, but Partho felt that was silly as the most brilliant projects failed either because of inadequate funding or improper planning of resources. He felt ideation should always be done with the resources in mind. Partho comes across as a Yama who always looks at numbers and milestones, especially when compared with his very popular boss, Wilfred, who is clearly a Kama. But he is actually a Bhoj, highly creative, but lets the reality of resource availability determine the limits of creativity.