Canada Under Attack (13 page)

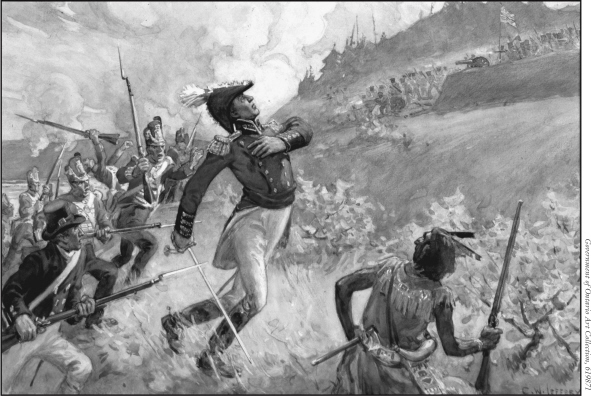

The Death of Brock at Queenston Heights.

The terrified Hull, who had his daughter and grandson inside the fort, asked for a three-day truce. Brock gave him three hours, then frightened the hapless general even more by telling him the lie that the Native warriors would “be beyond control the moment the contest commences.”

6

Hull immediately surrendered. Brock and Tecumseh rode into the fort side by side. Brock was resplendent in his uniform, and wore a beaded sash â a gift from Tecumseh â tied around his waist. Tecumseh, in his far simpler fringed buckskin, looked equally impressive.

Brock had, it is said, gifted Tecumseh with his own military sash. But Tecumseh, with a customary lack of conceit, had given it to another chief, Walk in Water, whom he considered of higher rank than himself.

Brock had won another decisive victory. But such victories would soon be harder to come by. The United States military commanders decided to focus their next attacks on the Niagara Region and in a hard fought battle there, Brock was killed leading his men in a charge up the infamous Queenston Heights. His men rallied at his death and managed to turn the battle around just in time. By that time, the commander was so well respected that men on both sides of the border attended his funeral.

After that, the longest undefended border in the world erupted in flames. Raids were launched and battles fought in numerous towns and forts along the border: Fort Erie, Frenchman's Creek, River Raisin, Brockville, and Ogdensburg. In a victory more symbolic than strategic, the Americans burned down the Canada East capital of York. A few months later, the British and Canadians would launch a retaliatory raid of their own on the American capital of Washington D.C., burning down the White House and forcing the president to flee.

Ordinary Canadians, many of whom had only recently fled the American Revolution as Loyalists, were drawn into the war effort. Homes and farms were looted and served as battlegrounds. In one small house in Brockville, the Americans barged in and demanded to be fed supper. While they ate, the young mistress of the house listened avidly to their conversation and then trudged 32 kilometres through swampy terrain to warn the Canadian commander, Lieutenant James Fitzgibbon, of an impending American attack. Laura Secord is credited with ensuring the success of the Canadian forces at Beaver Dams against a much larger American force.

As the war dragged on, the violence became more pronounced. Atrocities were committed on both sides. In one horrifying incident the entire town of Newark was destroyed in a raid lead by the Canadian traitor, Joseph Willcocks.

At dusk on December 10, 1813, Willcocks and his men, accompanied by a few American militiamen, rode into the town of Newark. They were incensed that the American commanders had earlier called a retreat across the Niagara River.

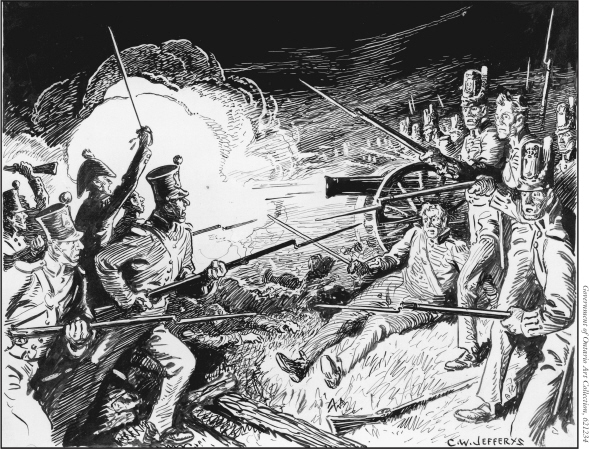

The Battle of Lundy's Lane.

As Willcocks and his men surveyed the town, the townspeople were warned to take what they could from their homes and leave. It had been snowing all day and it was bitterly cold. Willcocks started the burn at the home of an old political foe, a Loyalist by the name of William Dickson who had already been arrested. Willcocks carried the firebrand himself. He went upstairs to find the elderly Mrs. Dickson in bed. She was too ill to walk, so he ordered two of his men to carry her outside. The men wrapped the old woman in blankets and set her in a snowdrift. She watched in anguish as Willcocks burned her home to the ground.

There were other, equally horrific stories from that night. One young widow with three small children was turned out of her home with nothing but a few coins. After Willcocks's men plundered and torched her home, they took her money as well. In all, 400 women, children, and elderly men were turned out into the snow that night.

William Merritt, the captain of the Provincial Dragoons cavalry unit, had been on an assignment in Beaver Dams that day with British Force Commander Colonel Murray. As they were making their way back home, they saw the eerie orange glow of the fires in Newark. They guessed what had happened and raced to the scene, but they were already too late. Of all the horrifying scenes Merritt had witnessed during this war that was the worst. All that was left of Newark were glowing embers and charred buildings. Of the 150 homes in the town, only one remained standing. The townspeople had crowded into every room until the house could hold no more. Those left outside huddled in the drifts and beneath makeshift shelters. Some, terrified there might be more attacks, had stumbled off into the freezing night to seek shelter at outlying farms.

The streets were scattered with the remnants of a once prosperous town. Furniture, clothing, dishes, and personal treasures were everywhere, all abandoned by people too cold to carry them. The next morning, Merritt and his men found the frozen bodies of the women and children who had been seeking shelter outside the town. They had lost their way in the blackness of the night. As many as 100 women and children had perished that night in Newark â Willcocks had certainly had his revenge. Soldiers and civilians were equally horrified at this atrocity. The burning of Newark, more than any other action in the war, united the Canadian and British troops and the civilians.

On the Atlantic coast the British maintained a tight blockade and Canadian privateers harried the coast, but it was the Americans who dominated the inland water. By 1813, the Americans had Lake Erie in a stranglehold, with a seemingly unbreakable blockade at Amherstburg on the Detroit River. When Sir James Yeo sailed into Lake Ontario to assume his new position as commodore and commander in chief of the British Navy in the Canadian Great Lakes, he immediately decided that he needed to concentrate his attention on Lake Ontario. Lake Erie was expendable, Lake Ontario, which served as a vital supply line for troops on the Niagara frontier, was not. That philosophy left the Lake Erie force chronically short of ships, men, and supplies. The American blockade made the situation much worse. Food supplies at Amherstburg were running out and there was no more money to pay the army. Sailors had been put at half-rations.

The first major attempt by the British to regain control of the lakes ended in defeat at Sackets Harbour. With the American Navy preoccupied with supporting a raid on Fort George, the British commanders saw an opportunity to attack the American naval base at Sackets Harbour. Then they would burn the newly completed American frigate USS

General Pike

. The British lay anchor several kilometres offshore and the soldiers quickly climbed into flat bottom boats to make their way to shore. They'd gone only a little way before Lieutenant-Governor Prevost thought he saw ships in the distance and, fearing the return of the main American fleet, called the men back. It was a false alarm, but Prevost still refused to call on the attack and they waited until morning. This gave the Americans time to call out the militia. What was supposed to be a quick and easy victory for the British had turned into a complete rout.

Finally, the British naval and army commanders at Fort Erie, Robert Barclay and Henry Proctor, felt that they had no choice. Barclay suggested that waiting was still the more prudent approach but Proctor was adamant: they had to break through the American blockade. The battle of Lake Erie raged for four violent hours, with devastating losses on both sides, before the British finally surrendered.

For the first time in the over 300 year history of the British Navy, it had been handed a complete defeat of one of its fleets. The American response to the victory was surprisingly understated. “We have met the enemy,” wrote Oliver Hazard Perry, “and they are ours.” The defeat forced the British and Canadians to abandon Fort Amherstburg, leaving the field open to Indiana Governor William Henry Harrison, who quickly launched an invasion and pursued Proctor all the way up the Thames River. For months to come, the Americans would dominate Lake Erie.

Terrified of losing the Native alliance, the British tried to convince Tecumseh that the British had won the battle of Lake Erie. Tecumseh was no fool. He knew the British had been defeated, and he suspected they were planning to retreat. Retreating from the Americans was unthinkable to the proud chief. But since he was in an alliance with the British he had no choice. On October 5, 1813, while covering the British retreat up the Thames River with the Canadian militia, Tecumseh decided to make his last stand. He positioned his warriors on the far edge of a great swamp, and placed Proctor and his men to the left on some high ground between the Thames River and the swamp. He told the militia to take up a position between the two groups. Reviewing the position of the British, Tecumseh cautioned Proctor to stand firm. Then he returned to the swamp to wait. There was no trace of the compassionate, literate man. With war paint on his face, and hate in his eyes, he was the quintessential warrior. The American troops arrived at the battleground. The two armies faced each other for several hours, barely 275 metres apart, while the Americans formed their lines. Finally, they were ready for combat. One battalion charged the British, and then a group of Kentucky militiamen advanced towards Tecumseh. The hardened men yelled, “Remember River Raisin” â the site of a British-Native victory and a subsequent scalping earlier in the war â as they spurred their horses forward. As Tecumseh had predicted, the horses got bogged down in the thick marsh, and the Americans were forced to continue on foot. Tecumseh's warriors cut them down.

The respite did not last long. The British line had broken and Proctor's soldiers were running for their lives. Tecumseh and his men had been abandoned. Harrison's troops closed in. When the warriors ran out of ammunition they fought on with their tomahawks. Tecumseh's chilling war cry echoed through the forest; then it was silenced. The great chief was never found. It is generally believed the warriors took his body with them when they retreated. There is no official record of Tecumseh's death and no official marker over his final resting place. But to this day the Shawnee elders say they know where he is buried and that the location of his grave has been passed down from one generation of select leaders to the next.

Wherever Tecumseh lies, the hopes of a Native peoples' confederacy were buried with him. The grand alliance between the Native peoples and the British was finished. The last of the nations made peace with the Americans, and the lands that Tecumseh had fought to keep free were sold to settlers. The Native peoples of Tecumseh's generation lived the rest of their lives on small parcels of reserved lands.

In the spring of 1813, with their advance into Upper Canada at a standstill, the Americans turned their attention to the less heavily defended Lower Canada. Their aim was to capture Montreal and cut-off the critical British supply line from the Atlantic. They discussed their plans in detail, unaware that Canadian spies were eavesdropping and taking the information back to a young lieutenant-colonel in the British Army. This officer, a French Canadian aristocrat with the imposing name of Charles-Michel d'Irumberry de Salaberry, was aware of every move the Americans made.