Canada Under Attack (17 page)

Durham's report aside, the rebellions also served to finally dispel the widespread American notion that Canada was ripe for the taking. The vast majority of Canadians, including those who incited rebellion, had no interest in joining the United States. Their ferocity in defending their country was as unmatchable as it was unbeatable.

CHAPTER EIGHT:

AROOSTOOK â THE ALMOST WAR

We'll feed them well with ball and shot.

We'll cut these redcoats down,

Before we yield to them an inch

Or title of our ground.

â American Fighting Song, Bangor, Maine, 1839

The Americans may have given up on the idea that the Canadians were eager to join them, but that did not mean they'd given up trying to acquire all, or at least part, of Canada, by whatever means necessary.

In 1783 two empires, one old and established the other young and hungry, met in Paris to end the Revolutionary War. Among the items that the British and American representatives debated was who would claim a large tract of land known as the Aroostook Valley. They struggled with Article 2, which was intended to describe the northeastern border of the United States,

From the northwest angle of Nova Scotia, to wit, that angle which is formed by a line drawn due north from the source of the St. Croix river to the highlands, along the said highlands which divide those rivers that empty themselves into the St. Lawrence, and those which fall into the Atlantic ocean, to the north-western most head of the Connecticut riverâ¦.

It was an imprecise description to say the least. Both Maine and Britain claimed large, overlapping parts of the territory. But in 1783, the negotiators were unconcerned. The Aroostook was unmapped, sparsely populated, and filled with dense forests that made it barely inhabitable; definitely not something worth fighting for. By 1840, however, the world was a different place. Urbanization and expansion created an insatiable appetite for lumber and the demand reached previously unimaginable levels. Suddenly these vast tracts of forested land became almost as valuable as gold. Just as suddenly everyone wanted the Aroostook. “This whole region is a mighty forest,”

The New Yorker

magazine poetically wrote. “The rivers hollow out a path through the trees and the sparse settlements make windows in the broad forest landscape.”

1

An eclectic collection of people populated the area. French Acadians inhabited much of the Saint John and Madawaska river valleys while Americans settled near the Aroostook River. Near the west bank of the Saint John River were the British. The French speaking residents of the Madawaska were technically British subjects, but they felt no allegiance to either the British or Americans. They referred to themselves instead as residents of the

République du Madawaska

. Added into this mix of people were the hundreds of seasonal lumbermen who bedded their farms down for the winter and then polled the Saint John River in search of lumber. Inevitably there were tensions â between the permanent residents and these seasonal entrepreneurs and between the separate encampments of Americans, English, and French.

For more than 100 years, North America had been in a near constant state of war as the European nations battled for control of the continent. By 1814, Britain had emerged as the sole global power and the rebellions had been quelled. The tumultuous relationship between Britain and its former colony, the United States, had calmed. But it would not last. In 1819, John Quincy Adams, then U.S. secretary of state, claimed that

the world must be familiarized with the idea of considering our proper domination to be the continent of North America. From the time we became an independent people, it was as much a law of nature that this become our pretension as the Mississippi should flow to the sea. Spain has possessions upon our southern border and Great Britain upon our northern borders, but it is impossible that centuries should elapse without finding them annexed to the United States.

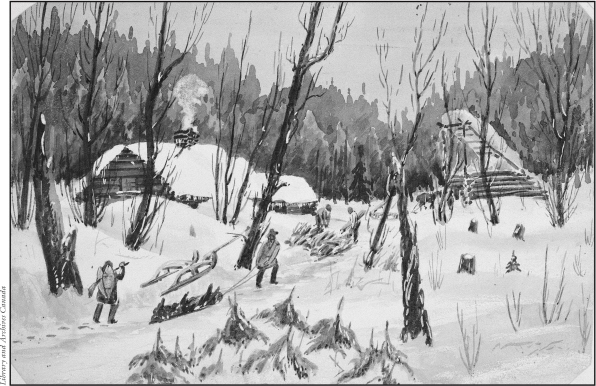

Alumber camp in the disputed Aroostock region, January 1854.

In 1840, the Aroostook seemed a good place for them to start that annexation. For part of the War of 1812, the British had occupied large tracts of land in the Aroostook and Saint John river valleys, intending to annex the lands to Canada once the war ended. But the Treaty of Ghent restored the ambiguous borders of the Treaty of Paris and with it the competing claims of both the U.S. and Britain to the valley. The situation was further exacerbated when Maine gained state hood in 1820 thereby inheriting the dispute over its northeastern border. The young state was determined to pursue her claim and the riches to be found there. In 1825 a great fire destroyed much of the forests in New Brunswick, along with the homes and properties of thousands who were living there. After he viewed the devastation, the lieutenant-governor of New Brunswick, George Stracey Smyth, claimed that the Aroostook and St. John valleys, with their rich stocks of lumber, were critical to the survival of the colony.

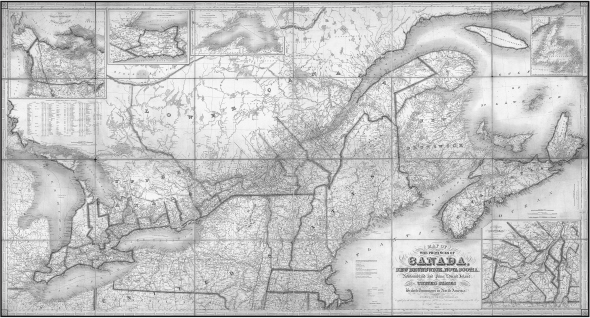

Map of the Provinces of Canada, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and Prince Edward Island, with a large section of the United States and showing the boundary of the British dominions in North America, according to the treaties of 1842 and 1846.

In an effort to resolve the dispute, the U.S. and Britain appointed separate commissioners to map the area. Not surprisingly, the commissioners were also unable to agree and eventually both claims were laid before William I, the king of the Netherlands, who had agreed to settle the dispute. The arguments for both sides were extensive and centred on everything from historical evidence to the definition of the Atlantic Ocean. The U.S. brief alone was reportedly 588 pages long, the British 418 pages. In 1831, William I selected the Saint John and St. Francis rivers as the border between Nova Scotia and Maine. The effort was clearly a compromise and almost immediately accepted by Britain. The Maine legislature, under pressure from lumber interests, refused to ratify the decision. Once again the border was in dispute.

A few months after they rejected the border suggested by King William I, Maine was still determined to secure the territory it regarded as its own. Despite warnings from President Andrew Jackson that they should refrain from acting on their claim, the Maine Legislature decided to incorporate the village of Madawaska, along with over 10,000 square kilometres of land in the disputed territory. Elections were held in the village but some, including the French settlers, refrained from voting. Regardless, they held a town meeting attended by some 40 citizens and elected several town councillors before British officials arrived to disband the meeting. At another meeting encouraged by Maine officials, they met to choose a representative to the legislature. This time, the lieutenant-governor of New Brunswick became involved. He arrived in Madawaska with the New Brunswick attorney general, a local sheriff, and a complement of militia and promptly arrested four of the men who were most heavily involved with the Madawaska elections. Three of the four were fined $50 each and imprisoned for three months in a New Brunswick prison. In March 1832 the government of Maine accepted what amounted to a secret, million dollar bribe from Washington to refrain from pursuing their claim to the region. Washington intended to accept the recommendations of King William I but Maine withdrew from the secret pact and the Senate was forced to reject the arbitration.

Mutual frustration built on both sides of the border, along with the size of the troops massing there and within the disputed area. Settlers had no idea if they were American or British citizens. Also at issue were the hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of timber in the region, timber that was steadily growing in value as the dispute wore on. Dispatches were sent to both Washington and London, seeking support. The U.S. government was not anxious to launch another war with Britain and in Britain; Prime Minister Lord Palmerston considered the Aroostook problem to be little more than a nuisance.

Palmerston sent word that Britain would continue to exercise jurisdiction in the disputed area until a settlement could be reached. But a settlement seemed unlikely in that climate. Given the terms of union, the U.S. Senate was unlikely to approve a settlement that Maine did not support and Maine itself seemed to be quickly adopting a take-all or take-war approach. As a compromise, Palmerston suggested that each side appoint a commissioner to investigate the claims of both sides. They were further given instructions to survey the area and locate geographical features mentioned in the 1783 treaty. Suspecting that what Palmerston was really looking for was compromise rather than the truth, and not wishing to antagonize Maine, the U.S. government rejected Palmerston's suggestion.

Until they could negotiate a treaty the two sides agreed to create a virtual no man's land where no country claimed sovereignty. For a while the arrangement seemed to work and lumbermen from both sides arrived every winter to cull the forests. But in 1837 Congress passed a bill that would distribute proceeds from land sales to the states. Since the amount would be based on the state's population, Maine dispatched a land agent to produce an official census of the disputed region along the border in order to bolster their claim to the funds. The land agent, Rufus McIntyre, was a scrappy 70-year-old who was spoiling for a fight with the British. Reports filtered out that Mr. McIntyre was offering money to encourage settlement in the disputed area. But when McIntyre's men arrested a dozen so-called trespassers, including James McLaughlin, the New Brunswick appointed warden of the disputed territory, outrage overcame caution and the New Brunswickers were soon marching toward the valley. McLaughlin had already been transported to a prison in Bangor. At 1:00 a.m. on the night of February 12th, 40 armed men surrounded the house in which McIntyre and his companions slept. They arrested the men and McIntyre reportedly demanded to know by whose authority they were arresting him. “By this authority,” the commander responded, brandishing his bayonet.

2

McIntyre and his companions were taken to Woodstock where a magistrate issued a warrant against them. They were then marched to a prison in Fredericton. Officials gamely offered to release the men if they agreed to quit the area. When McIntyre refused, the solicitor general of New Brunswick assured him that he would supply him with a note that would explain that the man had no choice but to abandon his task or be imprisoned. Again he refused.

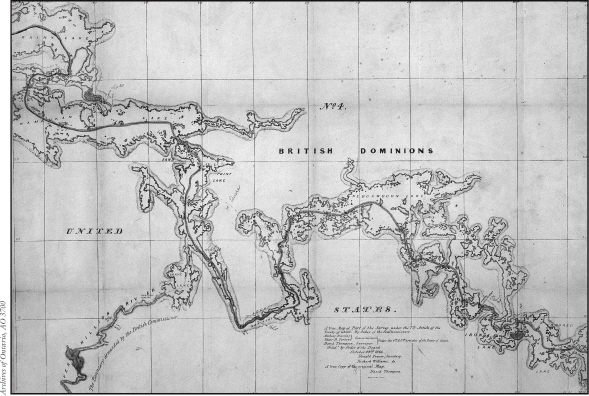

A true map of the survey under the seventh article of the Treaty of Ghent by order of the commissioners, 1826.

Outraged by this apparent attack on Maine's own soil, a posse was formed and immediately set off with the goal of rescuing McIntyre or taking revenge on the Canadians. By the middle of March, Maine had amassed over 2,000 troops in the Aroostook Valley. The legislature met and voted an additional 10,000 troops and approved $800,000 in funds for the defence of the state. New Brunswick also massed their troops along the border and ventured into the disputed territory. In response, Maine warned that if challenged its soldiers would not hesitate to retaliate.