Canada Under Attack (21 page)

After a series of secret meetings complete with secret passwords, skepticism, arguments, and threats of blackmail, von Brincken finally agreed to pay the crafty von Koolbergen $1,500. Von Koolbergen promptly disappeared with his winnings and without having committed any punishable crime. The Canadians were left without their evidence.

German espionage and sabotage in Canada died off once the United States entered the war and German operatives no longer had a safe haven south of the border. But the extent of the German effort in Canada during the First World War was astounding. In addition to sabotage efforts against rail lines, canals, factories, and military targets, they recruited hundreds of operatives in Canada, including those from the Irish Canadian and Canadian Sikh communities, whom they supported in their fight for independence from Britain.

CHAPTER ELEVEN:

U-BOATS IN THE ST. LAWRENCE

May 11, 1942, dawned bright and clear and the people of Gaspé, Quebec, went about their business in much the same way that they always did. There was a war in progress â many of the people in this region had sons, brothers, and fathers fighting overseas â but the war itself seemed far away and less immediate than the commonplace tasks of everyday life.

The weather held throughout the evening. A half moon rose over the bay, casting it in a soft, bluish glow. The tide lapped gently along the shore. A few hours after midnight the dulled sounds of a distant explosion were heard. Then a much larger, much closer crash. Finally, the sky lit up with the lights of what seemed like a thousand fires. A few hours later another boom shook the coast and the glare of yet another fire coloured the horizon.

The war had come to Canada.

A mere 13 kilometres from shore a German U-boat had sunk a British banana boat commissioned to carry war supplies. Boats rushed out to rescue the survivors but it was too late for six unlucky sailors. Just as the exhausted survivors stepped onto shore, the second explosion lit the sky. The Dutch freighter

Leto

, leased by the British Ministry of War, was hit. Passing ships picked up what survivors they could find clinging to the wreckage and small rafts. The U-boat had struck so quickly and with such precision that the men of the

Leto

only had time to launch a single, small boat. A dozen seamen lost their lives.

The attacks shocked Canadians. Knowing that U-boats were busy in the St. Lawrence was one thing, actually being forced to witness an attack was quite another.

Until 1942 there had been no definitive German plan to attack in North American waters. The few U-boat attacks that had occurred in Canadian waters, particularly in the St. Lawrence, were considered to be accidents of chance or opportunity. In fact, U-boat crews attained a sort of mythical status in Canada. Tales abounded of U-boat captains arriving in villages to buy their groceries, have a beer in the local tavern, or enjoy a dance with a pretty girl in a local dance hall. Far from being a threatening element, the U-boats almost seemed romantic. All of that changed after the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbour. Germany was officially at war with the United States and all of the previous restrictions placed on U-boat commanders by a German High Command eager to avoid antagonizing the Americans were abandoned. A flotilla of five large U-boats was dispatched to Canadian waters. Operation Drumbeat had begun.

With the majority of Canada's few naval vessels engaged elsewhere, only a minesweeper, two motor launches, and a small yacht remained to protect the entrance to the St. Lawrence. The area was considered to be a secondary target by both the Germans and the Allies and therefore of secondary importance for defence. Even Operation Drumbeat was meant to be a lightning strike rather than a sustained action. It turned out to be a devastating action that more closely resembled a prolonged storm. The combination of freshwater from the river, saltwater from the ocean, and rapidly fluctuating temperatures wreaked havoc on sonar equipment in the gulf. The area's notorious fogs helped hide the U-boats when they broke the surface. By the end of October, U-boats had sunk 19 merchant ships and two naval escorts.

The most devastating attack was yet to come. The

Caribou

had ferried citizens between Sydney, Nova Scotia, and Port-aux-Basques, Newfoundland, for years. On the morning of October 14th it was torpedoed by a German U-boat, a mere 60 kilometres from its destination. The ferry went down so quickly that only one lifeboat could be launched. The crew valiantly urged people into the lifeboat and when that was full they helped them on to pieces of debris and makeshift rafts. Other crew members lead disoriented, panicked passengers away from the sinking hull of the ship. When the last survivors were finally rescued they learned that only 15 of the 48 crew members had survived.

Many of the crew had gone down with the ship, others helping to save as many as they could before they were forced to abandon ship. Despite the crew's heroic efforts, the numbers were grim. Of the 237 souls who had set sail for Newfoundland that morning just over 100 survived. The loss of the

Caribou

ripped the heart out of Newfoundland. There were five pairs of brothers amongst the crew and several fathers and sons. Most were lost. Also lost was the Canadian sense of distance from the war, which had seemed so far away. The death and devastation that had, until then, been confined to a distant land had come home to Canada.

In August, U-boats launched attacks against ships in harbours in Labrador and Newfoundland, and against a convoy in the Straight of Belle Isle. The continued U-boat attacks fuelled a bitter debate over conscription in the Canadian Parliament and damaged the already fragile relationship between Quebec and the federal government. Quebec members of Parliament were furious over the seemingly inability of the government to protect their coastal constituencies. The Royal Canadian Air Force frequently tracked the U-boats but just as frequently lost them in the fog or was grounded by the mercurial Maritime weather. The quick moving U-boats frequently attacked before the ships were able to gather into the safety of a convoy. In September,

U-517

entered the St. Lawrence River, was almost immediately detected, and came under heavy fire from the RCAF. It was still able to escape and sink nine ships. By October 1942, U-boats had penetrated as far upriver as Rimouski, Quebec, just 300 kilometres from Quebec City.

The Germans did not stay long in the St. Lawrence. Instead they turned their attention to targets that were more lucrative and easily attacked. Military authorities had long expected an attack on highly exposed Bell Island. Its harbour was frequented by large ships and the iron ore mined there was in high demand from the various war machines. Early in the war the Canadian government had agreed to furnish Bell Island with several large guns and searchlights to aid in the defence of the harbour. The Newfoundland government recruited a militia, the Canadians provided training for the men, and the iron ore companies provided the barracks to house them. Air Raid Patrol wardens patrolled the island's streets to ensure that lights were doused and curtains drawn during blackouts.

On September 5, 1942, the harbour was full of ships. The

Saganaga

and the

Lord Strathcona

, each with their holds filled with iron ore, waited for a convoy to escort them to Nova Scotia. The

Evelyn B

was loaded with coal and waiting to unload. Numerous other ships â the

PLM 27

,

Rose Castle

, and

Drake

pool

among them â were busily exchanging the goods they had delivered to Bell Island for loads of iron ore. On the

Lord Strathcona

, Chief Engineer William Henderson watched as a torpedo tore through the calm waters of the harbour and slammed into the

Saganaga

. He checked his watch. It was 11:07 a.m. Less than three seconds later, “a second torpedo literally blew the

Saganaga

to pieces. Debris and iron ore was thrown up about 300 feet and, before the last of it had fallen back into the water, the

Saganaga

had disappeared.”

1

Henderson immediately ordered his crew to their lifeboats and at 11:30 a.m. as the men of the

Lord Strathcona

were still attempting to rescue the men of their sister ship, the

Saganaga

, another torpedo slammed into the

Lord Strathcona

. A second torpedo slammed into the ship and it sank less than a minute and a half later. The crew of the

Evelyn B

immediately opened fire into the water where the torpedo had first appeared and is credited with driving off the U-boat, which was still lying in wait. The militia joined the fight from the battery and trained the heavy guns on the water.

U-513

suddenly broke the surface and raced to the safety of the open ocean.

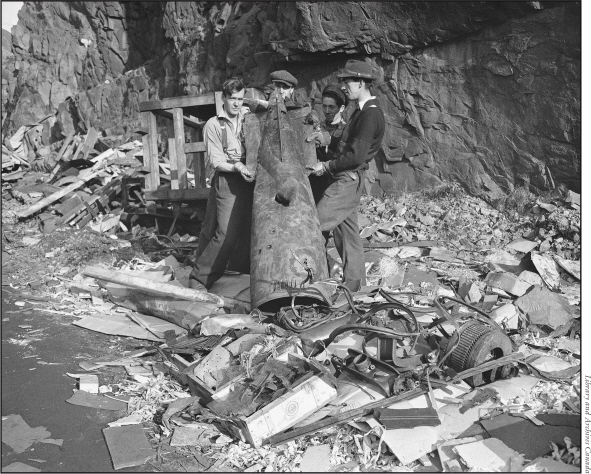

Damage to the Scotia Pier caused by a torpedo fired by the German submarine U-518 on November 2, 1942. Taken on Bell Island, Newfoundland, November 3, 1942.

The first battle of Bell Island was over. The second would begin just a few months later. On the night of November 2, 1942

U-513

's sister ship,

U-518

, crept into Conception Bay. The U-boat stayed above the waterline but hugged the craggy cliffs on the side of the bay, listening to the sounds of cars travelling on the cliffs above them as it crept closer to its target. The searchlights from the battery illuminated two ships at anchor. The U-boat commander fired at the first, the

Anna T

, but missed. The torpedo slammed into the Scotia Pier, blowing a portion of it to pieces and causing $30,000 damage.

2

The battery immediately responded and while the searchlights swung wildly in an attempt to locate the U-boat it fired again, sinking the

Rose Castle

. Once again the attacking U-boat was able to escape unscathed.

The Canadian government was so concerned about Newfoundland that it created a secret plan to burn St. John's to the ground should it be captured by the Germans. But Newfoundland was not the government's only worry. U-boat activity in the St. Lawrence did not slow and in 1942 was still showing signs of increasing. The Canadian government was busy contending with a growing rumour mill, its angry provinces, and frustrated allies.

On September 9, 1942, an exasperated Canadian government finally closed the St. Lawrence to all but local, coastal traffic. The closure had no discernible effect on North American shipping and was seen as more symbolic than strategic. However, the closure did mean that the ships would no longer have to wait in the dangerous Gulf for other ships to arrive from Montreal and Quebec City before forming a convoy to cross the Atlantic. It also shifted the centre of Canadian shipping away from Quebec and into the Maritime provinces.

Buoyed by their successes in disrupting Atlantic shipping routes, the Germans discovered another use for their U-boats. In May 1942, they landed a spy using the alias of Lieutenant Langbein in the Bay of Fundy, New Brunswick. In November a U-boat deposited German agent Werner von Janowski near the town of New Carlisle, on Chaleur Bay in the Gaspé region of Quebec. Von Janowski roused the suspicions of a local innkeeper's son when he used outdated money and Belgian matches. He was picked up by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police the day after he landed and soon agreed to act as a double agent for the RCMP. Langbein managed to remain in Canada undetected until 1944, but it is unlikely that he was inclined to do much damage as a spy. He and von Janowski had both been tasked with monitoring shipping traffic on the St. Lawrence but that traffic had virtually halted soon after they landed. In fact, RCMP records suggest the Langbein was a friendly man with an encyclopedic memory who had lived in Canada prior to the start of the war and was eager to take advantage of an opportunity to return. According to most contemporary reports, Langbein simply lived off the money provided to him by the German Foreign Office until it ran out and then he turned himself into Canadian authorities.

In September 1943 a U-boat left the village of Kiel, Germany, bound for Canada. Unlike the many other submarines that had gone before it

U-537

was not after North American convoys or cargo.

U-537

carried an interesting cargo of its own, a small group of scientists and technicians. Their mission was to land in Newfoundland and install a weather station nicknamed “Kurt” that could be used by the German High Command for assessing possible invasions of Canada and North America. The weather station was a complex instrument that was able to translate temperatures, wind speed, air pressure, and direction into Morse code and transmit the data every three minutes.

On October 22,

U-537

hovered just off the northern end of Labrador. Despite the danger presented by the numerous air patrols that swept the region, the submarine broke the surface and dropped its anchor. Under cover of one of the area's notorious fogs, the submarine waited at the surface while technicians muscled the 220 pound canisters containing the weather stations components onto rubber boats. The Germans had cleverly marked the canisters with the Canadian Weather Service logo in order to forestall any suspicions should the canisters be discovered. The only problem was that there was no organization known as the Canadian Weather Service in 1943. The German technicians had also brought along American cigarettes and matchbooks to leave at the site and forestall any suspicions should the site be explored by the Canadians. They need not have worried. The remote weather site was never investigated by the Canadians or their allies. The station operated perfectly for a few days, sending out regular signals, and then it abruptly stopped transmitting. It was never used by the Germans.