Canada Under Attack (18 page)

In the midst of these escalating tensions, some more level-headed men released McIntyre, McLaughlin, and the other imprisoned men. But the newspapers on both sides of the border continued to whip up the populace. They condemned the arrests of citizens of their respective countries and suggested that the invasion of their cities was imminent. They celebrated their soldiers and extolled their citizens to be brave. “Let the sword by drawn and the scabbard be thrown away!” read the headlines of the

Kennebec Journal

. War seemed inevitable. In Upper Canada, Lieutenant-Governor Sir George Arthur declared, “I don't see how this can be ended without a general war.” In the U.S., citizens were further riled to learn that an American had been tossed into a New Brunswick jail for whistling “Yankee Doodle” and told that he would not be released until he learned to whistle “God Save the Queen.”

While the politicians postured and the soldiers rattled their sabres, the “war” began to take on an almost comical tone. One incident occurred when a group of American and Canadian lumbermen were drinking in the same tavern in apparent peace. When one mischievous soul raised his glass to toast Maine, a brawl broke out. According to local legend a pig that wandered in from Canada was shot, and one unfortunate Maine farmer's cow was taken hostage by the magistrate of Kent, New Brunswick â apparently it was later rescued by the Maine militia.

Inevitably, there was a darker side to the war. Soldiers would mysteriously disappear from their campsites and never return. A soldier by the name of Hiram T. Smith died, but no one is really sure how he succumbed. Explanations have ranged from being run over by a supply wagon to drowning in a local pond. Whatever the cause, a plaque was raised to mark the site of his death in the summer of 1839.

While the soldiers on both sides kept themselves busy building fortifications, the U.S. and British government's struggled to find a peaceful solution to the crisis. In the end, they appointed two men â Daniel Webster, a failed presidential candidate who had been given the post of secretary of state, and Alexander Baring, First Baron Ashburton. The two, who happened to be good friends, worked to find a solution that would be acceptable to all parties. For his part, Ashburton refused to relinquish any territories north of the Saint John River. The dispute was finally settled in 1842. The United States received 18,000 square kilometres and the British received 12,950. The British agreed to pay the Americans reparations while the Americans agreed to pay the British for expenses they incurred while defending the area. Webster met the senate in a secret session in order to convince them to support the treaty. During that secret meeting he produced a map that he had said he had found in the Paris archives while researching records of the boundary. The map was purportedly marked by Benjamin Franklin and apparently entirely supported the British claims. Today, most historians believe the map to be a clever forgery created by Webster to sell the plan or by someone else sympathetic to the British cause.

The Aroostook War was really the war that wasn't. It is alternately known as the Lumberman's War, for the lumberman who made up most of the Maine militia, or the Pork n' Beans War, for the food the soldiers ate while they waited in their camps for the war to start. It was a war that the fledgling state of Maine was to be eager for, but that both Britain and Washington were determined to avoid.

For over 20 years Canada's borders remained silent. Then the rumblings began. Throughout the winter of 1865 the good people of Campobello Island, the Nova Scotia colony, had listened to the rumours. A well-funded, well-organized, well-armed group of Irish American militants were hoping to pick a fight with the British. They were known as the Fenian Brotherhood and had been founded in 1859 in New York, as an offshoot of the Irish Republican Army. The two groups had a common goal â the liberation of Ireland â but they did not agree on the method. Some thought that an uprising in Ireland was the answer while others favoured an invasion of Canada as a way to get British attention. Most of the Fenians were battle-hardened veterans of the Civil War and most had found themselves unemployed when the war ended.

Fiercely loyal to Ireland and violently anti-English, the Fenians decided that if they could not launch an invasion and force the English from Ireland, they'd attempt the next best thing and force them from Canada. At worst, they hoped their fight would spark a wider conflict, pitting the entire United States against Britain. But what they most hoped for was to capture Canada and offer it in exchange for a free Ireland. By the time Campobello Island heard the rumours of an imminent invasion, the Fenians already had supplies in position along the border, generously provided by the demobilizing Union Army. All of Nova Scotia was a potential target. The colony was in the midst of a debate over Confederation and it was starting to look like voters would reject the idea altogether. The Fenians did not expect to meet much resistance. Campobello Island, isolated and sparsely populated, was at more risk than most and the people knew it. When a New Brunswick militia officer entered the general store to post a notice requesting new recruits, three patrons dropped their purchases and joined on the spot. By the time the Fenian sails were sighted, New Brunswick had 5,000 regulars, volunteers, and militia guarding its borders.

The military received intelligence, warning of an imminent attack, on St. Patrick's Day. Citizens were assigned to keep watch and the newly minted militia was mobilized. They waited but nothing happened. By the end of the month the rumours had quieted and everyone became anxious to get back to normal. The government disbanded the local militia and assured the people that all was well. It wasn't. By April 1866, 1,000 Fenians had gathered in Maine, directly across the water from Campobello Island. And more were on their way. Michael Murphy, a Fenian leader in Toronto, was ordered to bring a contingent of his men to the MaineâNew Brunswick border, but the telegram was intercepted by Canadian officials and Murphy and several companions were arrested on a train in Cornwall, Ontario. A substantial cache of cash, weapons, and ammunition was captured with Murphy. Murphy and his companions were jailed on charges of treason until they escaped and took refuge in New York City. News of the capture arrived alongside the news that the Fenians were gathering. In New Brunswick, the volunteers quickly mustered and two British ships were dispatched to wait out the conflict in the bay.

On April 17, the U.S. Navy boarded the

Ocean Spray

â a former Confederate ship that the Fenians had taken command of â took charge of the 500 rifles the ship carried, and warned the crew that that U.S. neutrality would be strictly enforced. The Fenians, confronted by an annoyed American government and facing a clear, strong resistance from the Canadians, delayed their plans to attack. The delay did not last long. In Niagara the Canadians had also received warning of an attack, but there was little they could do except wait. Attacking the Irish could be perceived as an attack on the Americans, something everyone wanted to avoid. As the sun skirted the edge of the horizon on the morning of June 1st, the sleepy residents of Fort Erie awakened to see a flotilla of ships sailing toward them. The masts bore a strange flag, a harp and crown on a field of green. On that cool, clear morning, a formidable force of nearly 1,000 Fenians slipped unhindered into their boats and rowed quietly across the Niagara River, pulling ashore at what is now the intersection of Bowen Road and Niagara Boulevard. They carried extra uniforms and arms with them for the flood of new recruits they expected to join them. They had come, they informed the local populace, to free them from the yoke of British tyranny. When no Canadians responded to what they viewed as an insane call to arms, the Fenians were astounded. What was wrong with these people? Did they not realize that liberty was within their grasp?

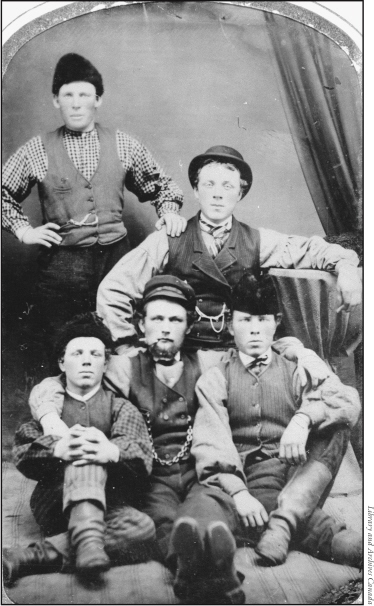

A Group of Fenian Volunteers, 1865.

The Irishman Doran Killian had a plan to seize the island of Campobello Island. His theory was that the occupation would keep the British troops from being sent back to Ireland, where the real revolution would take place. The American government did nothing to stop them â they were not willing to risk war with the Canadians, but they were not above allowing the Fenians to cause the Canadians and the British a few problems. After all, the Canadians seemed to have been a little too helpful to the Confederate armies.

For their part, the Canadians were more exasperated than afraid and certainly more annoyed with the Fenians than eager to join them. On Campobello Island the Irishmen ate a leisurely lunch provided by the locals â who were no doubt hopeful that if they fed this crazed bunch of marauders they would move on. Instead, the Canadians watched in fascinated horror as the Irishmen stretched out in the shade beneath a stand of maples to take a nap. But when the small group of invaders realized that expected reinforcements would not be arriving, they eventually left. To the Canadians it must have appeared that the Fenians were engaged in more of a social enterprise than a military one. Events would soon prove them wrong.

Undeterred by their failed raids on Fort Erie and Campobello Island, the Fenians turned their attention to Niagara. By May 22, 1866, almost 1,000 Fenian troops, led by Colonel John O'Neill and Colonel Owen Star, had massed in Buffalo, New York. While the Fenians were successful recruiters and fundraisers their successes made avoiding the attention of authorities almost impossible. British operatives easily infiltrated Irish American communities and knew every move the Fenians made. They made sure that the Canadian authorities knew too. Across the river, the Fenians quietly reported to their commanders and were then dispersed in smaller groups to the homes of local Irish Americans. At midnight on June 1, Colonel Starr rowed quietly across the Niagara River and quickly secured a landing point for troops at the Village of Bertie Township. O'Neill followed a few hours later with the rest of the troops. The plan was to take the Welland Canal, thereby cutting off the vital shipping route between Lakes Erie and Ontario.

By 9:00 a.m. two columns of troops marched beneath a bright green banner toward Fort Erie and the local rail yard. They were a motley bunch. Some wore “peculiar green jackets,”

1

others United States Army uniforms, but for the most part there was “nothing to distinguish them from an ordinary gathering of about one thousand men.”

2

O'Neill took a small group and headed for the local rail yard. A loaded locomotive had just pulled out of the station and a couple of the more adventurous men jumped onto a handcar to pursue the train. After burning down a bridge they gave up and rejoined the main group who had set up camp at Thomas Newbeggin's farm. At first, they met no immediate opposition and they did not attract the Irish Canadian recruits they hoped for. The extra 1,000 muskets they had brought to arm the recruits lay piled in a corner of the camp.

While 14,000 Canadian militia had been called up when the Fenians began to gather in Buffalo, only a handful were actually ready for service when O'Neill and his men arrived. The Canadians realized that the likely target was the Welland Canal and the rail line that ran parallel to it so troops were stationed at both the south and north ends of the canal: Port Colborne and St. Catharines. At Port Colborne that included 800 men, primarily young, eager college students from Toronto. They lacked heavy weapons and logistical support and were commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Booker, a Hamilton businessman with very little military experience. Booker received orders to join his forces to the regiments of more experienced British regulars under the command of Colonel George Peacock stationed in St. Catharines. Early on the morning of June 2, Booker's men boarded rail cars that would take them to Ridgeway. From there they would march to Stephensville to meet Peacock and his men.

O'Neill had his own spies in the Canadian and British camps and he knew he would stand little chance against the combined numbers of Peacock and Booker's.

His only option was to attack Booker before he reached Stephensville. So while Booker was loading his men onto railcars, O'Neill gave orders to several regiments of his Irish Republican Army (IRA) to launch an overnight march to Ridgeway. By the early morning hours of June 2 they had taken up position on Limestone Ridge just north of Ridgeway. Colonel Booker and his boxcars full of soldiers arrived at Ridgeway, where several local farmers informed him that the Fenians were already there. Inexplicably, Booker ignored that information and at 6:00 a.m. he ordered his men to begin their march along Ridge Road toward Stephensville. The men moved forward but were forced to leave their reserve ammunition behind when it became clear that no transportation had been arranged for it. They had not gone far when two Canadian detectives arrived to inform them that the Fenians had fallen in behind them. Almost simultaneously they heard the sound of rifle fire. Booker immediately ordered his men to take cover and return fire. He expected Peacock to arrive soon. Peacock had received reinforcements during the night and they refused to budge until they finished their breakfast. Peacock had no idea that Booker's troops were already under fire. Luckily, it appeared that Booker's young Canadians did not need any help from the British regulars.