Cell Phone Nation: How Mobile Phones Have Revolutionized Business, Politics and Ordinary Life in India (4 page)

Authors: Robin Jeffrey

RADIO FREQUENCY AND MOBILE PHONES

A radio wave is an electricity-driven spurt

of energy. Think of the ripples a stone makes when it falls into a pond. A big stone makes big ripples—with long gaps between each one; a small stone makes small ripples that are closer together.

This is where the term ‘radio frequency’ comes in—how close together, or how frequent, are the electro-magnetic waves that a transmitter spurts out. Old-fashioned AM radio works at frequencies between 535 and 1700 kilohertz. That means the signal or wave oscillates at between 535,000 and 1.7 million cycles every second. If a radio station is assigned a particular frequency (say, 621 kilohertz), people with receivers tune their receivers to pick up only radio signals bumping along at 621 kHz.

AM radio uses relatively low frequencies because that was what the technology was capable of producing when broadcast radio became possible after the First World War. Advances in technology have brought the ability to transmit at higher frequencies—more oscillations per second—and therefore to pack more information into each time interval because each interval contains a larger number of cycles.

Because the range of Radio Frequency (RF) suitable for economic and technological exploitation is finite, there have been national and international agreements since the 1920s about what sorts of uses, and which organisations, may operate on particular frequencies. For example, 2.402 GHz and 2.480 GHz (that is, 2.402 billion and 2.480 billion cycles per second) are set aside for industrial, scientific and medical devices (ISM). For most of us, these are the frequencies that operate garage doors

and Bluetooth. These devices are driven by only tiny amounts of energy so their signal does not travel very far—only 10 or 15 yards or metres—and they therefore do not travel ten blocks away to interfere with someone else’s garage door.

Increasing refinement of how you can slice RF spectrum—how you can populate the radio waves with information—led to the first mobile phones and to the continuing refinements since the 1990s.

Because usable RF is limited, and users of mobile phones now number billions, you need to use the same frequencies over and over again in different geographic locations. Signals therefore have to be relatively weak. That’s why India needs 400,000 cell phone towers to pick up signals from friendly towers and re-send them to other friendly towers nearby.

That’s also why we talk about ‘cell’ phones. Each telephone tower covers a ‘cell’, a geographic unit which the telecom company has marked out (usually about 10 square miles or 26 square kilometres). The tower in one cell passes on signals to towers in neighbouring cells, and a phone stays connected to the network even as we travel. (It also means that the network, or the police or criminals, if they want to badly enough, can find us).

The expressions 2G, 3G and 4G stand for second, third and fourth generation technology—the new technologies that allow more electro-magnetic surfboard riders to be put onto a wave. 2G brought voice and SMSes. 3G gives moving pictures and interactive gaming. 4G promises huge increases in speed which in turn will enable more complex content and interactivity.

Since RF is deemed to be a public good of which governments are in charge, governments license chunks of RF to telecom companies in return for large rental fees. Contests to get RF licences on favourable terms lead to wheeling and dealing that can put phones into villages, entrepreneurs into penthouses and politicians into jail. Such possibilities feature in this book.

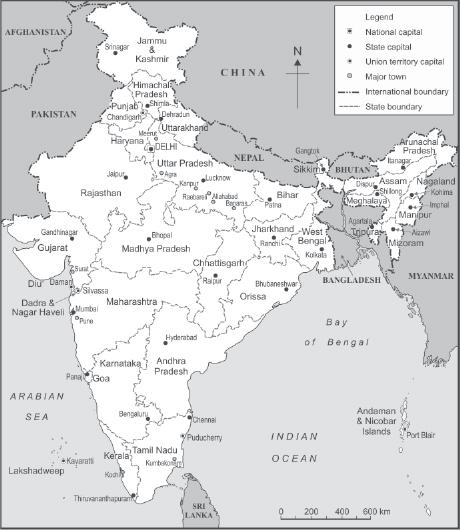

1. Union of India: States, state

capitals and places mentioned in the text.

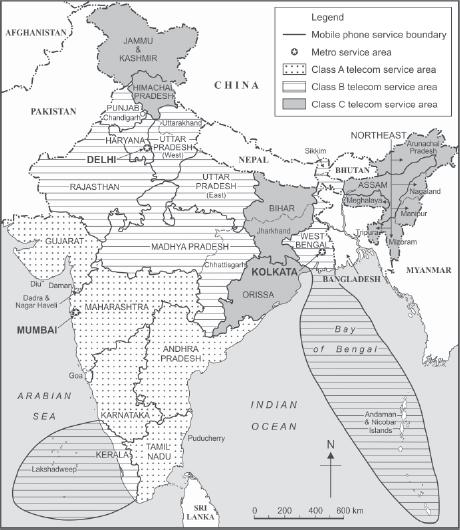

2. Telecommunications

circles: A, B, C and Metro circles as declared by the Government of India.

‘SO UNCANNY AND OUT OF PLACE’

If we were writing this book as a film script, the opening shot would show a pair of fine slippers lying beside an elegant double bed. Two well-pedicured male feet slip into them. A phone rings. A man’s hand picks up a fourth-generation mobile phone, on whose colour screen ‘unknown caller’ flashes, and the camera pulls back to reveal through a penthouse window the skyline of central Mumbai and the Arabian Sea. The film cuts to battered sandals on a pair of cracked, dusty feet, braced against the deck of what proves to be a large row-boat. The camera frames dawn on the River Ganga, the mist clearing to reveal the ghats at Banaras.

1

(See

Illus. 1

). Leaning on his oars, a boatload of foreign tourists behind him, a grizzled boatman, fortified against the morning chill by a little alcohol, calls into a battered Nokia, ‘

Kaun? Mittal Sahib?’

‘Who’s that? Is that Mr Mittal?’

The story unfolds … the boatman, complaining to the well-heeled overseas visitors about inadequate mobile-phone services, has been given by one of them the private number of ‘Mr Mittal’, founder and chief of a great telecom company, along with the supercilious suggestion that he should let him know of his problem. To the surprise of his patronising passenger, the boatman has no hesitation: he rings Mr Mittal.

The scene is our fantasy. It

has never happened; but it could. For the first time, even the poorest, lowest-status people in India can connect to the wealthiest and most highly placed. They can also connect with each other, and they can do so with little hindrance or constraint. Before the mobile phone, such connections were often difficult or impossible, as we describe in the first chapter of this book.

2

Cheap mobile phones gave poor people a device that improved their chances in a hard world. And in India, because of long-standing discrimination and structures of authority, the mobile has proved even more disruptive than elsewhere.

The focus on footwear in our imagined film script is intentional. The cheap mobile phone is the most disruptive device to hit humanity since shoes. That may seem a tall claim, but consider it. Like shoes, a cell phone allows people to communicate as they were unable to do before. Bare feet limit where you can go. The Vikings who were stealing up to slaughter the sleeping Scots, so the legend has it, gave the game away when their bare feet trod on thistles and they yelped in pain. A young Brahmin on pilgrimage in central India in 1857 echoed the limitations of bare feet: ‘my feet … were oozing blood. It was not possible to heal them, so, often, when the pain got acute, I would melt wax and seal the cracks’.

3

In the West, ‘until recent times … to be barefoot meant that all avenues of life were closed’.

4

The first quality of the male-chauvinist trinity of subjection—‘barefoot, pregnant and in the kitchen’—is ‘barefoot’. Like shoes, mobile phones have become an item that almost everyone can afford and aspire to.

5

Like shoes, they go everywhere an individual goes. Like shoes, they show off social class and ideas about fashion. Unlike shoes, mobile phones often get taken to bed. Compare the mobile phone to other devices that human beings have adopted in the past two hundred years. A pencil let you write outside in the rain; a box of matches let you make a fire whenever you needed to; a watch let you be punctual and encouraged others to expect you to be punctual;

6

a bicycle extended the range you could travel; an automobile let you travel when and where you wished, but needed a lot of money and space to park it. No personal item matched the ubiquity of shoes—until the cheap cell phone.

In India

The cell phone’s emergence meant

that Indians of every status were able to speak with each other as never before. Those possibilities arose through the widespread dissemination of affordable mobile phones. In February 2012, India had more than 900 million telephone subscribers; 96 per cent were subscribers to mobile phones. Even if we discount this figure by 30 per cent to eliminate duplication and non-active numbers, 600 million subscribers meant a phone for every two Indians, from infants to the aged.

7

Why are such figures particularly exciting in India? Cell phones have spread throughout the world. A survey in 2012, estimated that there were 6.2 billion mobile subscriptions in the world for a global population of 7 billion.

8

The World Bank pronounced ‘the mobile phone network … the biggest “machine” the world has ever seen’.

9

In developed countries, mobile-phone penetration exceeded a hundred per cent. Britain had 76 million mobile phones for 62 million people in 2012. In Africa, the spread of cell phones was also remarkable. Between 2003 and 2008, ‘Africa went from having almost no phones to a position where over 100 million Africans’ had mobiles.

10

By 2007, Mo Ibrahim, one of Africa’s early cell-phone entrepreneurs, could afford to sell his telecom companies, realise US $2 billion and set up a multi-million-dollar foundation to encourage African rulers to hold elections and transfer power voluntarily.

11

The richest man in the world was said to be Carlos Slim, the Mexican telecom tycoon, chairman of Telmex.

12

China made most of the world’s mobile-phone components and was estimated to have 900 million mobile-phone users in 2011.

13

Why the fuss about India?

India is both unique

and exemplary. Its diversity is unmatched; its caste system has no equivalent for endurance, complexity and malleability; and its experiments with democracy, development and federal government provide unrivalled examples of the potential and the limitations of human endeavour since the industrial revolution. Hierarchy in India was more refined and more deeply embedded in daily life than anywhere else. The lower your status, the less you were entitled to know, to ask and to travel. To be sure, such strictures have changed overtime, faced intense challenge, especially over the last hundred years and were outlawed by the constitution of independent India. But they endure: India remains a caste-conscious society. Mobile phones undermine these strictures. The poor, low-status boatman on the Ganga can conceivably ring India’s equivalent of Carlos Slim and can certainly call his friends and contacts and even a town councillor, senior official or Member of Parliament. Those at the top are likely of course to have minions deputed to answer official cell phones. But even if the person who is officially responsible does not answer, a citizen can make other calls: to a media outlet, an opposition party representative, an NGO or an influential relative. Importantly too, ‘big people’ have several phones, among them their very personal one, which they themselves answer—just as our imaginary Mr Mittal does in our film script. In the past, such connectivity was possible for only a very few people, and as late as 2000, these connections would have been impossible for most Indians. By plugging a large number of previously unconnected people into a system of interactive communication, mobile phones have inaugurated a host of disruptive possibilities.

We have written this book for people like us who wonder every day at head-spinning changes in technology and practices. We puzzle at new terms and ponder how telecommunications in the twenty-first century produced capitalist impresarios in the way that railways and automobiles did in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The contribution of

Cell Phone Nation

therefore is to try to paint a whole picture—imperfect and incomplete but

whole

—from the corporate captain in the Mumbai penthouse to the weather-beaten oarsman in a boat on the Ganga. Each has been affected by this simple-to-use device.