Cell Phone Nation: How Mobile Phones Have Revolutionized Business, Politics and Ordinary Life in India (5 page)

Authors: Robin Jeffrey

Other technologies of course prefigured mobile communication and profoundly affected human interaction. The railways, the telegraph and radio all increased the speed with which information could be transferred, and all had mixed implications. They reinforced state control over citizens and contributed to modern imperialism. The telegraph, in particular, made it quick and easy to transmit information across long distances, and governments and great capitalists guarded the technology and used it to mobilise military power, organise commerce and control vast territories. International news agencies, such as Reuters in Britain, Wolff in Germany and Havas in France, transformed telegraphic information into a commodity which they largely controlled.

14

There are many ways one

could study changes brought by the cell phone. We have borrowed a technique from landscape painters to try to capture a whole picture. Our canvas has been divided into three sections—

Controlling

,

Connecting

and

Consuming

. This invites readers to think about how communications were controlled in earlier times—how ‘information’ or ‘intelligence’ was valuable and was carefully collected and guarded by those who had it and how rulers feared too much knowledge being bandied about among their subjects. Printing presses in past centuries posed such challenges; but the ability to route Radio Frequency (RF) through a small, personal, cheap device to receive and transmit messages changed the way human beings could interact. It equalised—not wholly, but nevertheless significantly—people’s access to information, and began to undermine the epigram that freedom of the press was available only to those who owned one. Mobile phones made everyone a potential publicist. For governments, great corporations and entrepreneurs who would like to be great, the cell phone represented an immense challenge and opportunity.

From 1993 when the technology began to be deployed in India until 2012, the country had ten Ministers of Communication. One of them was convicted of corruption and sent to prison; a second was charged with corruption; a third faced probes that would take years to unravel; a fourth was murdered (though in circumstances not directly related to telecommunications); a fifth was undermined, overruled and rancorously removed.

15

For governments, bureaucrats, regulators and politicians, telecommunications offered a bed of thorny roses, and it is these contests over decision-making and power that we try to understand in the section on

Controlling

which forms Part 1 of this book.

The vast enterprise that bubbled up in the first decade of the twenty-first century generated a cascade of occupations and jobs. There are similarities to the way in which the automobile industry from the 1920s produced new activities and opportunities across the world. A book about the spread of car mechanics in Ghana in West Africa caught this effect well:

The small-scale industries of the informal sector form a complex matrix with innumerable interconnections. Every enterprise is both a consumer of others’ goods and services and a provider to others …

16

The mobile phone expanded

faster than the automobile. It was cheaper than a car, and many more people were involved in the chain that connected great Controllers to humble Consumers. In Part 2 of this book, we focus on the people who did the

Connecting

. They ranged from the fast-living advertising women and men of Mumbai to small shopkeepers persuaded by their suppliers of Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) to stock recharge coupons for pre-paid mobile services. In between were technicians who installed transmission equipment; the office workers who found sites and prepared the contracts to install transmission towers (400,000 in 2010);

17

the construction workers and technicians who built and maintained the towers; and the shop owners, repairers and second-hand dealers whose premises varied from slick shop-fronts to roadside stalls only slightly more elaborate than those of the repair-walas who once fixed bicycles on the pavement.

18

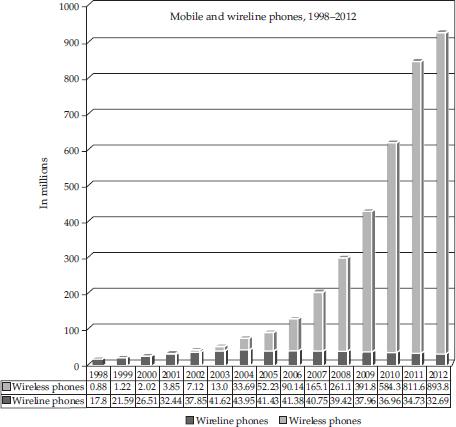

But it was the vast numbers of consumers that lent support to the claim that the mobile phone evened the odds—promoted a little more ‘equality’—between the powerful and the vulnerable. In the space of less than ten years, beginning from about 2002, India added 880 million phone subscribers. (See

fig. 1

). In 2002, there were about 45 million; by 2012 925 million. A majority of Indians acquired independent access to information and an ability to communicate that was highly valued and previously unimaginable. Poorer Indians were not unique in valuing the cell phone. In China, researchers concluded that

the less advantaged … (people with low levels of education, low income and rural origins) … felt that the mobile phone widened their communicative and social networks not only quantitatively but qualitatively.

19

For India, the mobile phone was the most widely shared item of luxury and indulgence the country had ever seen. It quickly became not a luxury but a necessity for tens of millions of people—the single largest category of consumer goods in the country. India’s decennial census in 2011 revealed what journalists found remarkable. The country had far more mobile phones than it did toilets of any kind: 53 per cent of the country’s 247 million households still defecated in the open; but mobile-phone density in 2012 approached 75 per cent. In hilly states like Himachal Pradesh, where mobile phones saved hours of exhausting travel, teledensity was 82 per cent.

20

Fortunes, if they were

to be made, lay at the bottom of the pyramid (BOP). The wealth that digital technology and Radio Frequency could generate had to come from use by the masses, and such use meant that handsets and mobile connections and services had to be cheap. As one of the prophets of such business plans explained, ‘the basic economics of the BOP market are based on small unit packages, low margin per unit, high volume, and high return on capital employed’.

21

India developed the cheapest mobile call rates in the world and turned pre-paid mobile-phone plans into a complex and much talked-about subject. In 2010, a US dollar (Rs 50) bought more than 200 minutes of talk time on an Indian mobile phone; in Australia, it often bought less than one minute. For the same investment, you drove your phone more than 200 times farther in India than in Australia.

22

Fig. 1: Phone subscribers in India, 1998–2012, Wireline and Wireless, in millions.

Source:

TRAI Annual Report.

Once the mobile phone

reached ‘the masses’, the masses became consumers. They occupy the third part of our canvas—

Consuming

—in a multitude of ways. Mobile phones were used for business and politics, in households and families and to commit crime and foment terror. Some of the practices enabled by the mobile phone were new and disruptive. At the most fundamental, mobile phones made fishermen’s lives safer and sometimes more prosperous. They got warnings of storms and tip-offs about the market for their fish, fewer of which went to waste. Farmers had similar experiences. More information about crops, pests, irrigation and prices was available to more people, and sometimes the ‘middle man’ could be bypassed and higher prices for crops and livestock obtained (

Chapter 5

).

But the phone was only a tool. Its effects depended on the knowledge and resources of the people using it, and ‘middle men’ usually started with advantages that ‘lesser’ men and women did not share. In politics, the mobile phone was a device that allowed organisations that were already bound together by convictions to exert influence in a manner that hitherto was impossible. The state elections in Uttar Pradesh in 2007, which brought an outright victory to the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), owed much to the way mobile phones allowed true-believers to tell the BSP’s story and urge sympathetic voters to the polls (

Chapter 6

). Mobile phones also facilitated crime and terrorism. Indeed, they created new crimes—harassment through text-messaging and faceless frauds where money disappeared without a victim ever seeing the criminal. Mobile phones made vivid pornography more widely available than conceivable in the past. And mobile phones enabled gullible young terrorists to be directed like human drones by remote ‘controllers’ (

Chapter 8

).

The ability to broadcast independently—to be an autonomous individual, no longer dependent on literacy, post offices, printing presses or television studios—created a potential to change accepted practices and malpractices, including exposing low-level corruption. Citizens now could record or even video their exchange with an official and use such material to expose slack performance or demands for bribes. Older technology had made video exposés possible. In 2001, for example, the Indian Defence Minister resigned after

Tehelka

magazine carried out a video-recorded ‘sting’ in which a party functionary was shown receiving a suitcase full of money.

23

But simple technology soon enabled recording to be done even on cheap mobile phones by ‘ordinary people’. At such possibilities, bribe-taking officials might tremble or at least have a momentary tremor.

But need they? Through

his relationships in Banaras, Assa Doron experienced the highs and lows of the possibilities. In 2009, a local boatman discovered his brother’s body hanging in his room. The surviving brother believed it was murder provoked by rivalry on the ghats (riverside mooring areas). With his cell phone camera he took pictures of the scene to convince the police to register a case of murder. (In such circumstances, the police usually aimed to close a case quickly as a suicide.) In spite of his evidence, however, the surviving brother failed. His pictures elicited no sympathy among the police officers he was able to approach, and he lacked the resources and influence to take his case higher up the bureaucratic chain or to the media. A few years later and he would have been able to post his pictures on Facebook or a similar website, and from such exposure greater pressure might have been brought to bear on the police, just as an advertisement for Idea cell-phone services depicted in 2012.

24

This vignette illustrates both the potential and limitations of mobile autonomy. The boatman had his phone with him—we always carry them with us—when he found his brother’s body, which enabled him to capture the scene. But such evidence alone was not enough to force action. Without capable institutions and well-drafted laws, lone citizens are limited in what they can achieve. Shirin Madon illustrated this point with the example of an apparently successful e-governance project that nevertheless was ‘dependent on the District Collector—that is, on a special relationship’.

25

Even the well-known online exposure in 2002 of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church in the United States, which Clay Shirky celebrated as an example of the power of the new technology, required the authority of an institution, the

Boston Globe

, to make the campaign of outrage effective.

26

In the world

One can envisage the

mobile phone as a crucial part of a grand theory of social practice and communication. Manuel Castells argued in the 1990s that humanity was experiencing

The Rise of the Network Society

in which ‘digital networking technologies … powered social and organizational networks in ways that allowed their endless expansion and reconfiguration’.

27

The ‘material basis’ now existed for the ‘pervasive expansion throughout the entire social structure’ of the ‘networking form of social organization’.

28

The cheap mass mobile phone provided that ‘material basis’, a device by which vast numbers of people acquired the capacity (and the need?) to be part of this ‘network society’.

Since the late 1990s, anthropologists have often asked two broad questions about the effects of the mobile phone: ‘How do people use this new tool? Does it change patterns of behaviour or simply reinforce existing practices?’ To try to get a grip on the variety of global experiences, pioneering research by Horst, Miller, Katz and Ling sometimes drew on concepts labelled ‘domestication’ and ‘performativity’ to describe the encounter between humans and technology.

29

‘Domestication’ involved the ways in which new devices—in this case, the mobile phone—became part of daily life: how people adapted, appropriated or resisted them to fit with their own needs and circumstances. Many of the essays in the path-breaking

Perpetual Contact

dealt with themes that related to the arrival of the mobile phone in Europe in the 1990s.

30

How and why did people incorporate it into their daily lives? Pure sociability appeared to be one reason—the human desire to interact with others. Other studies treated ‘domestication’ as a process characterised by ambivalence. As the technology entered people’s lives, they had to deal with its varied effects: on household economies, parenting practices, intimate relationships, youth culture and much else. Values and meanings were reshaped in the process: how people regarded ‘public’ and ‘private’ or the proper roles of men and women in control of technology.

31