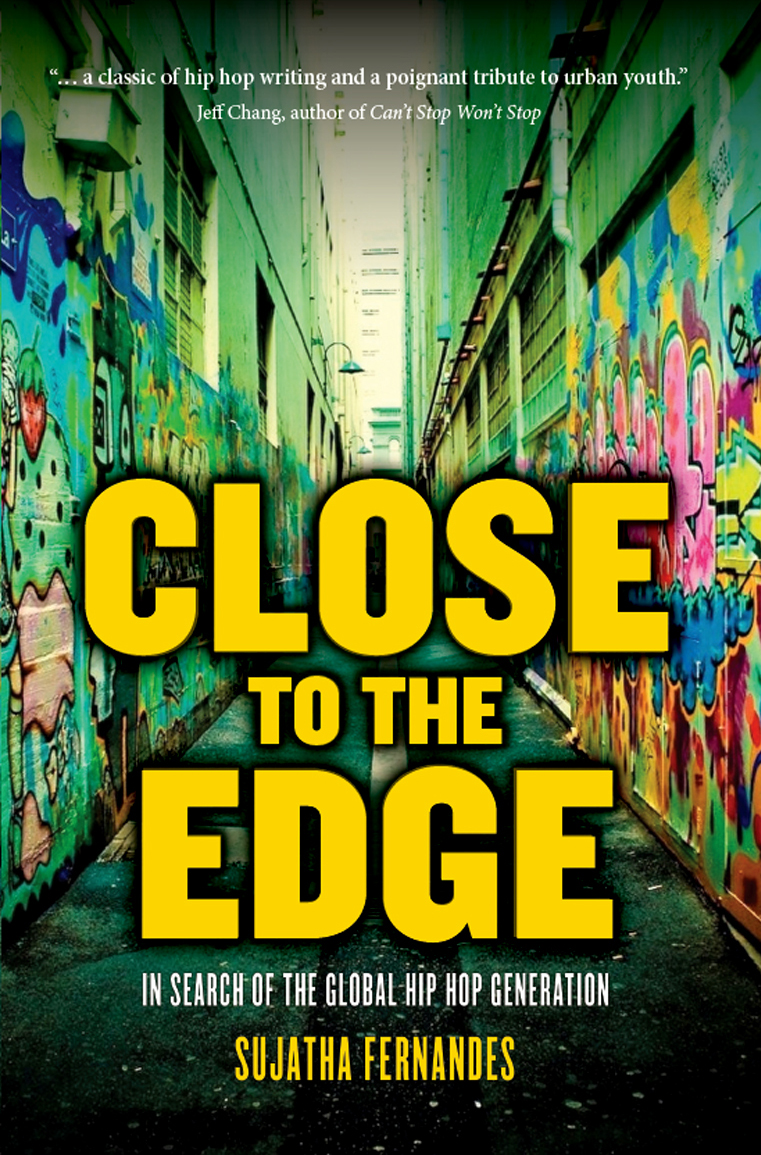

Close to the Edge

Authors: Sujatha Fernandes

TO THE

EDGE

IN SEARCH OF THE GLOBAL HIP HOP GENERATION

SUJATHA FERNANDES

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

© Sujatha Fernandes 2011

First published by Verso 2011

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Author: Fernandes, Sujatha.

Title: Close to the edge: in search of the global hip hop generation/by Sujatha Fernandes.

ISBN: 978 174223 311 6 (pbk.)

Subjects: Hip-hop â Influence.

Hip-hop â Social aspects.

Rap (Music).

Popular culture.

Dewey Number: 306.1

Typeset by

MJ Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Cover

John Yates

Printer

Ligare

This book is printed on paper using fibre supplied from plantation or sustainably managed forests.

For Mike Walsh

Contents

Introduction. The Making of a Hip Hop Globe

2. Down and Underground in Chi-Town

Preface

Â

Don't push me cause I'm close to the edge

I'm trying not to lose my head

It's like a jungle sometimes, it makes me wonder

How I keep from going under.

âGrandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, “The Message”

L

ate one Friday night in my teenage years, I was watching the Australian music video show

rage

, and I saw a flashback video of the 1982 rap hit “The Message.” I was growing up in Maroubraâa working-class beachside neighborhood of Sydney that was bordered by a jail, a sewage treatment plant, and the project-like Coral Sea Housing Commissions. I was captivated by the raw and angry lyrics that laid bare ghetto realities in Reagan's America. Back then I didn't know the story behind the songâthat, although it was credited to the legendary Grand-master Flash and the Furious Five, it was mostly written and recorded by a session musician not even in the band, and the band members who appeared in the video were lip-synching to the song. But there was something fitting about my close identification with a fabricated product that revealed so many truths. Any imagined connection I felt to an American ghetto was contrived at best, yetâand I don't know whyâthe song struck a chord with me.

My interest in hip hop had begun with lessons in b-boying at a workshop run by the Randwick Municipal Council. After we saw Michael Jackson's video clip

Thriller

, all the kids at my school wanted to do the moonwalk. But, unlike the b-boys and b-girls in the Bronx, who developed the dance styles at house parties, outdoor jams, and school hallways, we were taught the moves by our local city authorities. I was mesmerized by the scratching and raw energy of rapping in Run-DMC's “Walk This Way” on

Countdown

, a music show presented by an Egyptologist in a cowboy hat named Molly.

Salt, Pepa, DJ Spinderella, and Neneh Cherry were my role models and my guide to male-female relationships through the angst of adolescence. They created images of black beauty and sexuality that had not been available to us in Australia. When they talked back to menâ”Don't you get fresh with me,” and “Yeah, you, come here, gimme a kiss”âthey inverted the game of male pursuit that we had come to see as the norm. My friends and I would go to the downtown clubs like Kinselas to dance and hear the latest music. We used the music to escape the small and parochial world of our classmatesâof Saturday night drinking binges and casual hookups at local working-class pubs known as Returned Servicemen's Leagues (RSLs).

My growing fascination with rap music paralleled my political awakening. At college in the early 1990s, I joined a youth organization, Resistance, and became a full-time activist. At the time I was spending hours in the secondhand music stores along Pitt Street downtown, discovering records from Boogie Down Productions, Digable Planets, Public Enemy, and A Tribe Called Quest. My cousin Miguel Dsouza had the first hip hop radio show in Sydney, where I heard political rap from the States. The godfathers of rap, The Last Poets, had prophesized that the revolution was coming. It seemed that, with the intifada in Palestine, the Fretilin guerrillas in Indonesia-occupied East Timor, and rebellious youth facing down tanks in the streets of Jakarta and Durban, global revolt was imminent. So why didn't anyone on my block know it?

It finally dawned on me one day. I was with other, mostly white, activists, handing out leaflets at Sydney's town hall to protest the spate of deaths of Aboriginals while in police custody. But all the Aboriginal kids were walking right on past us. Just around the corner b-boys had laid out their cardboard strip and were doing head spins and windmills. I watched the crowdâimmigrant, Aboriginal, and white kidsâthat was gathering around them. I realized then that hip hop culture was speaking to them in a way that we activists were notâcould not.

It was this revelation that sparked my quest to find a global hip hop generation. Afrika Bambaataa had talked about a “Universal Zulu Nation.” KRS-One had rapped, “In every single âhood in the world I'm called Kris.” Chuck D had described the collective consciousness of a black planet. Inspired by these spokespersons for a new era, I began what would become an eleven-year odyssey across four countries in search of what exactly it was that made hip hop such a powerful global force.

But before I take readers on this journey, I want to rewind a little, to think about how hip hop went global in the first place.

INTRODUCTION

The Making of a

Hip Hop Globe

P

edro Alberto Martinéz Conde, otherwise known as Perucho Conde, was probably the first rapper to compose a hit song outside the United States. A poet and comedian from the inner-city Caracas barrio of San AgustÃn, Conde was perplexed by the strange but catchy lyrics of the Sugar Hill Gang's 1979 hit “Rapper's Delight.” In 1980 he came up with a Spanish version that went to the top of the charts in Latin America and Spain.

Far from the outdoor jams and battles of the Bronx scene where hip hop originated, “Rapper's Delight” was packaged and designed for travel. But that didn't mean global audiences got it. Conde baptized his imitation “La Cotorra,” the term for a pompous and long-winded speech. Other take-offs surfaced from Jamaica to Brazil; in Germany the song was called “Rapper's Deutsch.” Cubans called it “Apenejé,” because nobody could make sense of the lyrics. As the first rap song to go global, “Rapper's Delight” embodied the mix of fascination and incomprehension that would accompany the spread of early rap.

By the early 1980s the global circulation of hip hop through the music industry was being paralleled by the efforts of hip hop ambassadors like Afrika Bambaataa to spread a message of black brotherhood and unity. Back in 1973 Bambaataa had founded the Universal Zulu Nation, a Bronx-based street organization that drew on the mythology of anticolonial South African warriors to redirect the energies of inner-city gang youth. In April 1982 Bambaataa released his single “Planet Rock,” an anthem for this nascent movement, which was producing chapters across the city. With its mix of European technorock, funk, and rapping, “Planet Rock” was a model of fusion that imagined unity across cultures the same way Bambaataa had created unity across gang lines.

As he toured Europe and England in November, Bam-baataa hoped to set the groundwork for the global spread of his movement. North African immigrant youth in the

banlieues

, or suburban peripheries, of Paris were attracted to Bambaataa and his message of black solidarity. Local chapters sprung up in Britain and Japan, where Bambaataa toured in 1985. In Brazil adherents like King Nino Brown preached “knowledge of self” and experience as the foundations of hip hop.

1

Bambaataa imparted an Afrocentric and socially conscious ethos to his global hip hop followers.

Bambaataa's mission, to forge a global hip hop community, echoed the aspirations of the Pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey. His mission was taken up by the next three generations. Chuck D of Public Enemy took Garvey's vision of a black planet around the globe in the late 1980s, visiting local communities while on foreign tours. The Black August Hip Hop Project was formed in the late 1990s to draw connections between radical black activism and hip hop culture. The group organized exchanges between militant rappers in the US, Cuba, and South Africa. And the new millennium was the era of diasporic rappers, who forged a politics of global solidarity from within the heart of empire.

These hip hop ambassadors had their counterparts among intellectuals such as Paul Gilroy, who proposed the concept of the “Black Atlantic” as a space of exchange, belonging, and identity among Afrodiasporic communities that surpassed national boundaries.

2

Music held a privileged place in the Black Atlantic, unseating the primacy of language and writing as expressive forms. But blackness did not always have to be the element connecting marginalized communities. George Lipsitz saw “Planet Rock” as part of an international dialog built on the imagination of the urban poor internationally who were suffering from the effects of global austerity policies imposed by transnational capital.

3

Another set of scholars has more recently used the trope of the Global Hip Hop Nation to express the diffusion of hip hop and its social location as a universal cultural space.

4

All these scholars saw the potential of the market for carrying important political ideas between cultures.

My own quest in this book mirrors the project of these ambassadors and scholars. Could hip hop create a fellowship of marginalized black youth around the globe? Could rappers be the voice not just of a postcivil rights generation in the American ghettos but of a generation of young people in the

cités

, housing projects, barrios, and peripheries of urban metropolises worldwide that has been excluded from the promises of a new global economy? Was there such a thing as a global hip hop generation, and could it act politically?

As I traveled the globe in search of this elusive community, I saw the ways that hip hop was being integrated into the arsenal, repertoire, and landscape of urban youth. Yet the more I probed, the more I became aware of the disconnect between localized expressions of hip hop. If something held them together, it was being lost in a haze of misunderstandings, cultural assumptions, and mixed signals. My own projected imaginings and desires were not being met with the enthusiasm I expected. The easy alliance of a hip hop globe was in danger of being rejected as a fantasy concocted and imposed by the West and rejected by the rest.

The same year “Planet Rock” was released, the single called “The Message” came out. It was credited to Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five. Where “Planet Rock” preached universal brotherhood and transcendence, “The Message” was an edgy take on ghetto life. Where Bambaataa envisaged a universal consciousness, “The Message” was concerned with the specifics of everyday survival.

5

Produced by Sugar Hill Recordsâthe same label that released “Rapper's Delight”â”The Message” was another manufactured product. At the same time, “The Message” came to represent a profound counterforce in global hip hop history. And it offered a lesson that could not be ignored.

Exactly this local specificity emerged as key in the global spread of hip hop. Hip hop was shaping a language that allowed young people to negotiate a political voice for themselves in their societies. As I learned through my travels, the genesis of hip hop in each case was highly dependent on the history, realities, and constrictions hip hoppers faced from within their own context. The Hip Hop Nation as a transnational space of mutual learning and exchange may not have been a concrete reality. But the transient alliances that hip hoppers imagined across boundaries of class, race, and nation gave them the resources and the platform they needed to tell their stories and provided the grounds for their locally based political actions.

Global hip hop was always marked by a tension between the desire for transcendence and the need to speak directly to local realities. As the hip hop journalist Jeff Chang has said, the incongruous visions of “Planet Rock” and “The Message” could be brought together only on the dance floor.

6

The music held spaces of possibility for unity and cross-cultural understanding that made it powerful. Yet the contradictions between the dual visions at the core of the culture would be replayed throughout global hip hop history.

M

y motivation for writing this book lies in the abyss that I encountered as I came of age in Sydney in the eighties. In the seventies and early eighties I was surrounded by social ferment and political engagement. I now look back on that time as one when people considered radical change a real possibility. I remember my dad and his brothers debating anarchism. During our school vacations my sister and I were sent to stay with my auntie Dina in western Sydney. I witnessed her work in the refuge movement, which protected women from domestic violence. I read about feminism and racism in the books in my auntie Joyce's houseâGermaine Greer's

Female Eunuch

and Toni Morrison's

The Bluest Eye.

I began a correspondence with my mum's cousin Nigel, a socialist activist who was working with the Pintubi Aboriginal peoples in the Northern Territory.

I reached adolescence in the mid-1980s. Unemployment was high because of a serious economic recession, public sector cutbacks, and the decline of manufacturing industries, all inspired by Thatcher-and Reagan-style free-market policies. The glass factory and Resch's Waverly Brewery on South Dowling Street were shut down and the old buildings lay abandoned, their windows cracked and blackened. In the working-class beachside neighborhood where I grew up, youth unemployment fueled problems of heroin addiction, crime, and violence between rival surf gangs. On cold winter mornings the beach was lined with idle youth, smoking weed or surfing. And the people around me gradually withdrew from politics and into their private lives.

Hip hop was one way out of the void I found myself in. In the conscious rhymes of KRS or the funky wisdom of Salt-N-Pepa, I found a path to political awareness. And I met others who had also found a voice through hip hop, as they too compared the political vibrancy of their parents' generationâfrom the Aboriginal land rights movement to the Cuban revolutionâwith the bleak political landscape in which hip hoppers came of age. In the media and in popular culture, our generation was labeled Generation Xâthe ignored generation, the nihilist generation, the apolitical generation. But these labels didn't describe the angry and politicized young people I saw embracing hip hop culture. Bakari Kitwana had used the phrase “hip hop generation” to describe African Americans who came of age in the post-civil rights era.

7

Given the conditions of unemployment, incarceration, and poverty afflicting not just African Americans, but young people from the

banlieues

of Paris to the hillside shanties of Rio, I wondered whether we could talk about such a thing as a global hip hop generation.

I traveled to Havana in the late 1990s, where I witnessed the formation and maturation of Cuban hip hop. Havana was the site of an international hip hop festival. I thought that on this revolutionary island I would find the kinds of transnational solidarities that made the Hip Hop Nation powerful. Not only was this global solidarity a mirage, but Cuba didn't seem as revolutionary as I had hoped. It would take a crisis from the North for me to appreciate the strategic ways in which Cuban rappers negotiated both their revolution and their place on the hip hop globe.

Meanwhile, I was living in Chicago and checking out the hip hop scene by night. What struck me was the value that Chicago hip hoppers placed on independence, especially after I'd witnessed Cuban rappers' reliance on the state. Did this multi-ethnic city hold the possibility for building an autonomous and truly diverse Hip Hop Nation? The city's segregation presented serious obstacles. This took me back to my participation in hip hop in Australia during the mid-1990s and forward to Caracas in the new millennium, where hip hop was tied in to networks of grassroots activism. When our generation came together as a political force, we could find fleeting moments of connection. But, as the Paris and Redfern (Sydney) riots would reveal, some of the most powerful uprisings of the hip hop generation came not from international alliances of activists and rap celebrities, but from the everyday struggles of ghetto communities around the globe.

Of course, one of the central issues of the book remains: Who is the “we” that makes up the global hip hop generation? The easiest part of the answer is the age groupâKitwana defines the hip hop generation as those born between 1965 and 1984. So that would include those of us now in our midtwenties to mid-forties. The harder part is the social demographics of that group. Chang tells us that the hip hop generation includes “anyone who is down.”

8

But, if we think of the historically marginalized communities where hip hop emerged, and the housing projects and tenements across the globe where it resonated, the global hip hop generation would not include an Australian Indian female with a doctoral degree and the means to travel around the world. In this book I use my personal narrative as a way to reflect on the nature and scope of the global hip hop generation. Underlying all my endeavors is the hope that some universal thread connects all of us who have been brought together through hip hop culture, especially those in the most vulnerable and impoverished sectors. But I also came to the realization that privilegeâwhether by birth or acquired, of skin color, nationality, or social classâwould always inhibit the attempt to create global communities.

T

he early elements of hip hop culture to travel internationally consisted largely of graffiti and the dance style known as b-boying. The 1982 tour of Afrika Bambaataa and the Soulsonic Force had included the pioneering b-boys of the Rock Steady Crew, the Double Dutch Girls, the DJ Grandmixer DST, and the graffiti writers FUTURA and DONDI. The small audiences that turned up at the venues on the European tour were able to witness these elements of hip hop culture live.

9

For the rest of the world, knowledge of graffiti and b-boying came from television and visual culture.

The classic 1982 film

Wild Style

, produced and directed by Charlie Ahearn, was a tribute to the elements of the culture. It was released in cinemas worldwide, including Japan, where the cast of the film went to promote it. Many global fans had their first glimpse of b-boying in the Hollywood blockbuster

Flash-dance

, released in 1983. In one brief scene Rock Steady Crew members b-boy to Jimmy Castor's “It's Just Begun.” Over the next few years Hollywood capitalized on the international success of Rock Steady's

Flashdance

cameo. Tinseltown produced a string of what Chang calls “teen-targeted hip-hop exploitation flicks,” including

Breakin', Beat Street

, and then

Body Rock, Fast Forward

, and

Breakin' 2: Electric Boogaloo.

10

These films served up a watered-down version of the culture, but they became some of the first hip hop artifacts to circulate the globe. Through both legit and bootleg copies, aspiring b-boys and b-girls everywhere saw the films, got out their cardboard strips, and in schoolyards, train stations, and on street corners they began to practice the moves.