Close to the Edge (9 page)

Authors: Sujatha Fernandes

“Nearly all of my friends in jail / My barrio full of the mothers left behind,” he rapped. “Some jump into the sea, others go crazy, commit suicide / Death is a phase of life / I look for an exit and I don't find it / I'm at the center of a pack of hungry wolves / In the bullshit of the streets.” Then they chanted on the chorus, “What will be, what will be, what will be / What will be of my life? What will be?”

“I study, she works, I hardly see my mother,” Randy continued his rap. “I'm missing my father, I don't know what will happen / For the last five years I'm the man of the house / Those who know me accept me and those who don't reject me / Because the streets have become my second home.”

At the end of their performance, the small crowd erupted into claps and cheers. His rap had spoken of the dramas of the marginalized barrios that the minister was talking about. But for the festival Randy and El Huevo's rap would have to be more sanitized than this. I looked over at the blank faces of the judges and felt a pang for Randy. This was not the positive and educational rap that I felt Magia was probably looking for. But maybe there was a still a chance.

A few auditions later the judges decided to wrap for the day. There was still another day of auditioning in Havana and then on to the provinces. Rappers anxiously waited to hear whether they had a coveted spot in the festival.

H

e didn't make it again.” Lily's tone was bitter when she called to give me the news about Randy. “Two years in a row. Last year they were rejected, but at the festival they were called up onto the stage and people loved them. This year, well, you saw the crowd at the auditions. The crowd was really into their performance, but that doesn't count for anything.”

“What happened?” I probed, my heart sinking. “What reason did they give?”

“I don't know. Randy is not in an agency. He doesn't have any connections. I know it's a form of censorship, too. His lyrics are too

fuerte.

He doesn't understand. He says to me, âMama, groups that are not as good as us, who don't perform as regularly as us, were accepted for the festival this year, but not us.'”

“I'm sure he'll get called on stage again this year,” I reassured her. “And people will eventually see that they are really doing great work.”

“I don't think so. What chance does he have of making it now? The rap festival is the ultimate recognition for your career. It's the path to getting into an agency, getting a CD contract, and actually getting paid for shows. Randy has no desire to rap anymore.”

“Tell him he shouldn't be discouraged by this. It's not a comment on the quality of his skills,” I reassured her. I really believed this. “He'll find a way around the official path to success. He'll find his own way.” But of this I wasn't so sure. Randy already knew there wasn't much place for him in the market, since he wasn't willing to produce a danceable sound and party lyrics. But he also felt rejected by the underground, for being too underground. This was different from Julio's experiences with the panel of professors, as the judges now were peers and equals. But if these judges wanted to hang on to their festival, they had to make sure that the groups they selected stayed within the boundaries of what was permissible.

F

or those who had the honor of performing in the annual hip hop festival, there was the ritual of securing the coveted back-stage pass for artists or a press pass. At the Alamar amphitheater there wasn't much of a backstage to speak ofâjust a narrow corridor where rappers huddled before entering the stage. The entrance fee was nominal. But more than the free entry, it was the thrill of having the blue-and-white pass enclosed in a plastic case on a string around your neck. It conferred an aura of celebrity, a sense of importance and urgency, even if all you were doing was walking back and forth along the bleachers, trying to score weed or buy peanuts.

I wasn't really expecting to get a press pass for the August festival. The pass was mostly issued to foreign journalists, film-makers, and select Cuban promoters. But after I spoke about Cuban hip hop on a panel at UNEAC a week before the festival, Tomás Fernández Robaina, a small and sprightly writer who was organizing the event, took my elbow and urged me to pick up my press pass on Friday at the Madriguera, a youth cultural center in Central Havana. Later that day I saw Ariel, who said that he had processed my pass and it would be waiting for me on Friday at 10 a.m. I felt smug in my newfound expectations of entering the ranks of plastic-bearing royalty. I should have realized that things in Cuba are never quite that easy.

The other thing I should have known is that when Cubans say 10 a.m., they never mean 10 a.m. At 9:58 a.m. exactly I was standing outside the Madriguera. The small cottage and open-air performance space at the Madriguera, formerly the residence of the independence-era general Máximo Gómez, was tucked away at the back of a wildly overgrown botanical garden. To get to the cottage from the main entrance on Carlos Tercera, you had to wrestle your way through a jungle of quietly spreading creepers, cedar pines, citrus, and majagua trees, fending off mosquitoes and other small ankle-biting critters. When I arrived at the Madriguera that day, there was not a soul in sight and not a sound besides the distant chugs and groans of the

camello

buses from Carlos Tercera.

Gradually, some kids in baseball caps and jeans began to drift in. An hour later Magia and Alexey showed up with some other rappers. They assumed positions on the benches outside, as if settling in for the long haul.

“¿Que paso?” I didn't understand what was happening. “They said 10 a.m. to pick up our passes, but it's after 11 and no one is here.” As the words escaped my mouth, I realized the stupidity of them. Magia and Alexey exchanged looks of resignation.

“Suyee,” sighed Magia, using the Cuban version of my nick-name. “This is Cuba.” It was a phrase I was to hear time and again.

By midday the Madriguera was humming with the excited chatter of rappers who were there to claim their backstage passes. I sat drumming my fingers on my canvas bag, checking my watch every five minutes, as if that would make the Youth League functionaries appear.

“Pizza, anyone?” Around 1 p.m. Alexey had gotten hungry and picked up pizzas from the street vendor across the street to nourish us as we waited. Perhaps

nourish

is too strong a word, as the pizzas were lumpy mounds of dough saturated in oil and sprinkled with a pungent rubbery cheese on top. You had to hold the pizza off to the side and drain off the rivulets of oil before attempting to eat it.

Finally, close to 2:30 p.m., Jorge and Arnaldo, two functionaries from the Youth League, sauntered in. They unlocked the cottage door. Once they had set themselves up inside, they began to call the names of rappers to come and collect their passes. One by one kids walked out with the precious plastic around their necks and grins on their faces.

As I sat outside, I strained to hear my name being called. Getting more and more impatient, I finally went into the cottage. Magia and Alexey were sitting with Arnaldo in one of the rooms.

“Look,” I said to Arnaldo, “I've been waiting here since 10 a.m., I was told my pass would be available then. It's now after 3 p.m. Please, can you just give me my pass so that I can go home?”

Arnaldo checked his list. “I don't see your name,” he said. “Sorry,” he added, before turning back to a conversation.

“Ahem,” I cleared my throat. “I don't think you understand. Tomás Robaina and Ariel Fernández both told me I would be getting a press pass, and they said I should pick it up here, today at 10 a.m.”

“Well,” Arnaldo repeated slowly, “your name is not on the list. There's nothing I can do.”

I looked over to Magia and Alexey. “Perhaps you should ask Ariel, maybe he has the pass for you,” offered Magia.

“No, he doesn't. Ariel told me to come and collect it here,” I insisted. “I waited here today for over five hours. You know that, you were with me. How can they tell me after all of this that they don't have a press pass for me?”

I wasn't getting anywhere, so I decided to try another tactic. “What about an artist's backstage pass? I'll be performing with Magia and Alexey at the festival.” Magia had asked me to sing backup vocals for the “La llaman puta” song.

Magia didn't say anything. Arnaldo shrugged his shoulders. My eyes burned with tears, born not only of frustration but of humiliation and a sense of betrayal. Why wouldn't Magia back me, argue my case with Arnaldo, question this ridiculous system? Rap was supposed to be antiestablishment. Around the globe rappers were speaking out against the powers-that-be. But I was starting to wonder whether Cuban rappers were so much a part of the system that they couldn't or wouldn't see its shortcomings. I hated myself for wanting the silly piece of plastic so badly.

“You make people come here and wait for hours, and then you say my name is not even on the list?” I lashed out at Arnaldo. “You know, I'm writing about all of these experiences and the way that you treat people.” Bringing up my writing was a bad idea. “There are people back in America who support the Cuban revolution, but they don't know about all of this bureaucracy that people have to go through.” Bringing up the

enemigo del norte

was an even worse idea. I was coming off as a self-righteous gringa, flaunting my foreigner credentials in a society where they were hardly going to win me support. I turned on my heel and walked out with a flourish, before Arnaldo could respond to my outburst.

On the way out I bumped into Jorge, who was sitting by the door. “Are you a foreigner?” he asked. “Yes,” I mumbled, as if that last outburst hadn't proved it. “Then we don't have your pass,” he responded. “All foreigners must pick up their passes at the ticket booth on the first day of the festival.”

T

he amphitheater in Alamar was a large open-air stadium with rows of concrete blocks for seating and patches of grassy area. It had been the site of the annual rap festival since the beginning. On the opening night of the festival in August 2001, the space was filled to capacity, with a sea of young people in baseball caps, bandannas, baseball jerseys, berets, guayaberas, and checkered shirts. The stage was bathed in alternating red and blue flashes from a strobe light. A set of turntables was mounted on a plank of wood held up by giant steel drums. At the front of the stage speakers towered over the audience. Draped behind the stage was a large Cuban flag, the red triangle with a five-pointed white star visible above the pumping fists of the performers on stage. To the left of the Cuban flag was a graffiti piece that read ALAMAR in block letters at the top.

The ugly cement construction of the amphitheater, typical of the surrounding housing projects, came to life with the resounding thrum of the bass, the energy of the crowd with its hands in the air, and the tags of graffiti covering the walls.

At the closing event the group Reyes de la Calle performed a song about the

balseros

, the Cubans who leave for Miami in boats. The rappers had wanted to include images of the

balseros

on a screen behind them. This was not acceptable to the president of the Youth League. He told Ariel, “CNN may be filming it, and this would lend support to the counterrevolutionaries.” So Ariel asked Reyes de la Calle to do the song without the images.

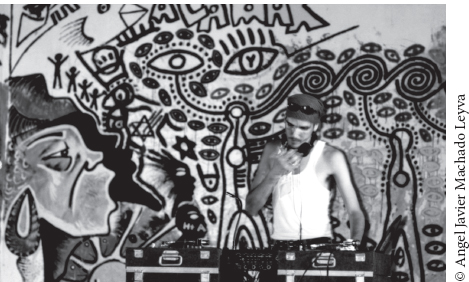

DJ Flipper at Hip Hop Festival in Alamar, August 2001

The Cuban government could support the rap festival so long as rappers stayed within certain prescribed boundaries. But some rappers wanted to talk about more controversial themes than before. How long would they accept directives from the Youth League president? Censorship was not always the most workable strategy. In these circumstances there was nothing like a crisis from the North to unite Cubans and give new fire to the meaning of revolution.

T

he United States is under military attack! They've blown up the World Trade Center! They've blown up the Penta-gon! Now they're blowing up Peeeeeburgh!” the grandmother in the house where I stayed in El Vedado was shouting from the living room. I came running out of my room. We flicked between the two channels available on state TV. The images of planes crashing into buildings were unreal. None of the commentators seemed to know what was going on. And why would anyone want to blow up Pittsburgh? It was several hours later that the news came through about the hijackers of four planes who had reduced the twin towers to rubble and crashed into the side of the Pentagon and an empty field in rural Pennsylvania.

I sat before the television watching the grainy images of the towers imploding over and over again. I was unsure if this was yet another Hollywood disaster movie or if it really happened. Fidel was involved in the inauguration of a new school that evening. Ariel came over, and we watched the live broadcast from the school where Fidel addressed a packed hall of elementary school kids. Fidel was resplendent in his military fatigues and for three hours cajoled, provoked, and meditated on the events of the day before a group of ten- and eleven-year-olds. He expressed his sympathies for the American people. He offered the resources of the country to assist in treatment of the victims. And he urged caution on the part of the American government.